Srinivasa Gowda at the Paivalike kambala in Kasargod. (Express photo by Nirmal Harindran)

Srinivasa Gowda at the Paivalike kambala in Kasargod. (Express photo by Nirmal Harindran)

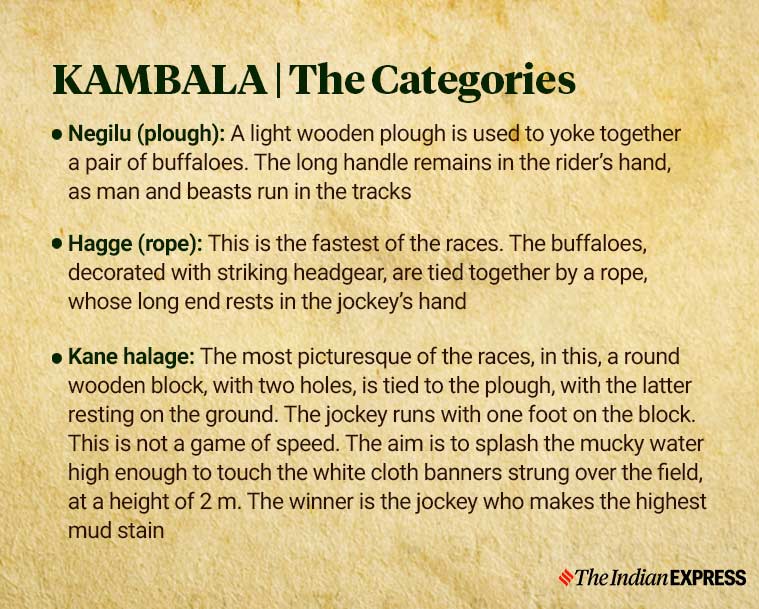

“Isn’t he the one? Usain Bolt?” asks a man, before walking up to a young man, clasping him into a half-embrace and scoring a selfie. His muscled torso gleaming in the evening sun, bare feet planted on earth, Srinivasa Gowda, almost a foot shorter than Bolt, is unlikely to be mistaken for the Jamaican sprinter anywhere else in the world. But in this village in Kerala’s Kasargod, where the pageant of kambala, a centuries-old agricultural tradition of buffalo racing, has made a stop this weekend, that is a minor quibble.

Here, Bolt is the electric charge in sluggish speeches, being invoked by dignitaries since morning to announce kambala’s arrival on the “international” stage. Here, the difference in mechanics between a human running 100 m in under 10 seconds to a buffalo-propelled dash in a 142m-long slushy track is settled by whipping out calculators. “It’s not just Gowda. Other kambala jockeys have broken the record last week,” says referee-cum-commentator Vijay Kumar Jain, pleased as punch at having announced the presence of a reporter from the international news agency AFP to spectators gathered in Paivalike, a village in Uppala, Kerala, only about an hour from Mangaluru.

A drone-camera whizzes drunkenly above — courtesy the Kasargod Vision news channel — not straying far from where Gowda is standing, with his entourage of buffaloes and helpers, ready to wade into the tracks for his fourth race of the day. The 28-year-old’s prowess as a prize jockey was known long before February 1, when he and his team of buffaloes ran 142.5 m in 13.62 seconds at the Aikala Bava kambala in Dakshina Kannada district, in the negilu eriya category. That led to the optimistic surmise, arrived via simple arithmetic (distance divided by time, then multiplied by distance), that he had beaten Bolt’s 100m in 9.58 seconds record by 0.03 seconds. “142.5 divided by 13.62, and then multiplied by 100. See, that comes to 9.55 seconds,” says Jain.

Buffalo owners perform a puja before the races begin. (Express photo by Nirmal Harindran)

Buffalo owners perform a puja before the races begin. (Express photo by Nirmal Harindran)

It’s difficult to say whose agile mind first came up with the comparison, but the tide of social media euphoria it produced got ministers talking, and nudged the Sports Authority of India (SAI) to send a team to Paivalike to hunt for athletic talent. But it still hasn’t convinced the man of the moment to wear a pair of shoes, forget spikes. “I have never worn them in my life. At most, I can wear slippers,” says Gowda, who, like all jockeys, will remain barefeet for the duration of the kambala.

A light flashes green as buffaloes and their rider barrel past the finishing line. A boy rushes in with a sloshing bucket; the jockey pours water all over his body, gulping some between breaths. Young Srinivasa was once that boy at the finishing line, watching hardy, lithe jockeys walk away with honours.

From a family of labourers, Gowda grew up in a village called Ashwathapura in Dakshina Kannada district. Nearby lived a landlord, whose buffaloes were trundled out during the kambala season. “I loved running in the mud, playing with buffaloes, giving them a wash in the river. Those were my childhood games,” Gowda says. The neighbour was his first mentor, taking him to the races as a part of his entourage. “That was where I first thought I could be a jockey,” he recalls. He studied till Class VIII, when he had to drop out and look for work, because the family couldn’t afford school anymore.

Nine years ago, he was a labourer at construction sites in and around Moodbidri, when he heard of trials for an academy to train kambala jockeys. Professor K Gunapala Kadamba, a connoisseur of the sport, worried at the “growing shortage of jockeys”, had organised funds to start the Kambala Samrakshane Nirvahane Tarabeti Academy in Karnataka’s Miyar. “We wanted that kambala should continue to the next generation,” says Kadamba. A student of the first batch, Gowda is now its most famous alumnus.

This season, Gowda has signed contracts with three owners, who pay him around Rs 2 lakh-3 lakh each to race their buffaloes. Unlike most other jockeys, whose only job is to race, Gowda also looks after three buffaloes owned by Harsh Vardhan Padhiwal, the owner of a restaurant in Moodbidri. “All I like doing is taking care of buffaloes. Even in my free time, I don’t watch films or yakshagana,” he says, as he gives Kaala, Raja and Bolla a coconut-oil rub at his newly-built house, a day before the race. “The angriest one is Raja. He is young and hot-headed. But he listens to me,” he says. “The oldest is Kaala. Can you see his teeth? Once a buffalo gets six of these, he is ready to play in the senior category,” says Padhiwal, whose team members sport yellow-and-red jerseys that announce “Moodbidri New Padhiwals”.

Gowda with his buffaloes at his newly-built house. (Express photo by Nirmal Harindran)

Gowda with his buffaloes at his newly-built house. (Express photo by Nirmal Harindran)

All buffaloes that run in kambala are male. Once crucial to cultivation, they have no place in mechanised agriculture. Rearing them is simply a mark of affluence. “They work only on weekends, and that, too, for three months in a year,” jokes Padhiwal.

Gowda is chatty when talking about the animals. “Around 5.30 in the morning, I take them for a walk near the house. Around noon, they are made to stand in the sun for one hour in the day. Then they are taken to the nearby river for a swim. They have to get exercise, after all,” he says.

While kambala has helped give his family (a parent, two sisters, two brothers, one of whom is differently-abled) more comforts, neither success nor this flare of fame has stirred Gowda out of the unhurried pace of his non-kambala life. He still works as a construction labourer through the week; he is content with an un-flashy black Splendour bike, and has no plans to replace his chipped Samsung smartphone. “Even this one is too much for me,” he says, with a smile that he will flash more than once in our conversation. “I do have a Facebook account but it’s my friend who manages it,” he says. A jockey is supposed to have broken his record in last weekend’s kambala but he is not drawn into rivalries. “That’s Nishant Shetty, my friend. We hang out together. I am very happy for him,” he says.

In this house he has built, surrounded by a patch of coconut trees, he potters around bare feet — “Our soles need to be tough” — pats his dogs, and shyly waits for Malabar Gold representatives to hand him a memento and shawl. Earlier in the day, young “fans” from his community, the Kudubis, a backward caste that is often confused with the more powerful Vokkaliga community, gather in a house to honour his achievement. He mingles easily, handing out water bottles and plates, refusing to slip into the role of a star.

Inky-back buffaloes, bedecked with colourful ropes or yoked by light ploughs, walk in twos into canals filled with mucky water. In Paivalike this morning, a pair is mutinous, refusing to line up at the starting point, contorting to free themselves of the plough tying them together. Another pair takes off, but lurches dangerously like an out-of-control autorickshaw. The thwack of the nagarbetta, the thin whip used by the jockey to hit the animal, rises above the yells of the rider, as they near the finishing line — a spectacle repeated through the day, as over 100 pairs of buffaloes compete for honours.

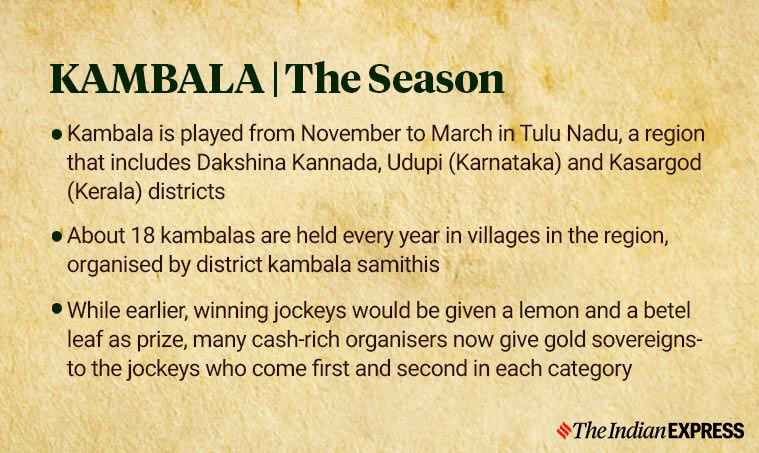

Watching the performances are the buffalo owners, dressed in white shirts and mundus. Drawn largely from the Bunt, Jain and Brahmin communities, they pump in money, organising skills and pride into 18 kambalas held from November to March in the villages of Tulu Nadu, a region that includes coastal Karnataka and this corner of Kerala. “Once you are in kambala, the mud sticks to you. You can’t get out,” says Ashok Shetty. He should know. The 33-year-old comes from a family that is a bit of a rural legend. Like many other migrants from this region, his uncle, the late Vinu Vishweshwara Shetty, travelled to Bombay in search of work, found a job at the many Udupi restaurants run by members of his community, and worked his way up to build his own hotel business in Dubai and Mangaluru. He returned to rear a prize-winning herd of buffaloes. In 2011, he built a swimming pool for them in his home in Padubidri, complete with a lounge area with music system, television and an air-cooler. “It was very hi-tech,” says Ashok.

A buffalo pair sports the sign of the cross on its headgear. (Express photo by Nirmal Harindran)

A buffalo pair sports the sign of the cross on its headgear. (Express photo by Nirmal Harindran)

In the 1980s, when Purushottama Bilimale, professor at JNU’s School of Language, Literature and Culture Studies, was researching kambala, he met many such prodigals. “The Bunts from Bombay would come for one day, with five gold rings on their hand, wearing white shoes and white shirts. They would donate generously,” he recalls. The tradition continues — hotel-owners from Mumbai this year contributed Rs 11 lakh to the Aikala Bava kambala committee.

The origins of the agricultural — some say feudal — sport lie in land. In Tulu, the word kambala means “a paddy-growing mud field”. “To plough, cultivate and harvest paddy, the labour of many people is required. In olden days, to till 10 or 20 acres, farmers would bring their buffaloes, about 200-300. At the end, the strong buffaloes, capable of running in slushy water, would race,” says Kadamba.

The birth, decline and modernisation of kambala — its conversion from ritual to sport — is also the story of its land. “As a ritual, it must have started in the 16th century, not before. That was the time when land changed hands, when the communities that make up today’s Tulu Nadu (Konkanis, Bunts, Gowdas of Sullia) migrated here. With them, came private ownership of land. The earlier inhabitants, the so-called Dalits — Koragas, Mailas, Mehars — had no such concept,” says Bilimale. The land reforms of 1974, brought in by the Devaraj Urs government, was a jolt to kambala. “Big paddy fields had to be broken up and divided. It was not possible to have a celebration like the olden days,” says Kadamba, whose family once owned about 800 acres of land. In the 1970s, the modern kambala began in Karkal, where two permanent, concrete tracks were laid. “That was the start of competitive kambala,” says Kadamba.

The sport lost its place with the fraying of the old order, but was soon galloping in step with the animal spirits of the new economy. “In the late 1980s and 1990s, the Bunts and Brahmins lost land but invested money in education and the hotel business in Bombay. That money they ploughed back in small plots of land, and into kambala, buying buffaloes, some as expensive as Rs 4 lakh -5 lakh. The Bunt was not a landlord now, but, every year, he symbolically regained ownership of land temporarily through kambala,” says Bilimale.

To the question — why play kambala? — the owners have a unanimous response: “pride” . Till a bolt of celebrity pitched Gowda and some jockeys into the limelight, all name in kambala accrued to the owners of land and capital. In the entire kambala, referees rarely announce the name of the jockeys or the bulls, who are identified by who they run for. The prizes — gold coins both for the winner and the runners-up — also go to owners. Most of the riders are peasants, hardworking men who swear by a diet of ganji oota (fermented rice) and meen (fish), some of them playing into their 40s and even 50s.

For a region with high religious polarisation, kambala remains a secular space, in which people of all castes and creeds take part. Dolphy D’Souza’s family has been racing for 40 years or more. As the team of buffaloes, named after parents Francis and Flavy D’Souza, walk into the arena, the sunlight bounces off their shining headgear, inscribed with silver crosses. Iqbal Habib, 32, has travelled with his friend Ashpak from Karkal, 100 km away, where he works as a driver. “We have reared buffaloes since I was a child,” he says of a family tradition that is at least 50 years old. At the start, when owners walked up to the shrine of Anna-Thamma for a puja, so did Habib. “In kambala, there is no Muslim or Christian or Hindu,” he says. “Everyone comes here, they put kumkum on their foreheads and start playing,” says Ashok Shetty.

Iqbal Saheb one of the owners of Buffaloes at Anna-Thamma Kambala organised at Paivalike in Kasargod district in Kerala. (Express photo by Nirmal Harindran)

Iqbal Saheb one of the owners of Buffaloes at Anna-Thamma Kambala organised at Paivalike in Kasargod district in Kerala. (Express photo by Nirmal Harindran)

For all talk of kambala’s tryst with modernity, it is, at heart, more a festival than a sport run by rules of science. The length of kambala tracks can vary from race to race. No records of timings have been kept through the decades. “That’s because there was no foolproof method of measuring it,” says Kadamba.

“Earlier, a jury at the finishing line would trust their eyes and decide the winner. Then, came the video replay. Then, a system where sensors would break only at the finishing line. But, sometimes, the person at the start could make an error in pressing the start button. During late-night races, they have even fallen asleep,” says Ratnakar Naik, programmer and drone cinematographer. The Paivalike edition sees a first for kambala — Naik has devised a system of sensors that break at both start and finish. “I can say that the timings now are accurate down to 0.03 seconds,” he says.

The leap from more-accurate timings to track-and-field performances is a long one. Ajay Kumar Bahl, senior director of SAI’s south centre, was at Paivalike to see if that jump was possible. “We wanted to see what kambala was all about. We found a slightly aged pool of talent. Nevertheless, we are thinking of Srinivas Gowda as our pilot project,” Let him finish his kambala races for the season, and then come to SAI,” he says. Gowda says he first heard of Bolt a few years ago, and watched him on TV. But he remains wary of plunging into athletics. “We shouldn’t compare. In kambala, you run in the mud, in another, on the track. Bolt can’t run in muddy fields, and neither can I suddenly run on tracks. Maybe I can with time,” he says. “I am happy with the attention because kambala needs a lot of love and encouragement. And I want more people to play it.” Even Bolt? “Yes, yes, let him come,” he says, laughing.

For many enthusiasts, the current spotlight on the sport is a welcome one, considering that a Supreme Court order banning jallikattu in 2014 had led to a ban on kambala, too. “Now it is world famous, ekdum posh. I don’t think we have to worry,” says Padhiwal. “Buffalo bulls aren’t anatomically or physiologically suited for racing and no amount of regulation can change this scientific fact. And that has been stated by the court in the May 2014 judgment,” says Dr Manilal Valliyate of PETA India. While PETA’s challenge to the Karnataka government’s amendment to the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Act, 2017, which insulated the sport from the ban, is yet to be heard by a Constitution bench of Supreme Court, owners talk frankly about the use of the contested nagarbetta. “They have to be hit, otherwise they won’t run and can’t be controlled,” says Padhiwal.

“It is wrong to call it himse (cruelty). Do we not hit our own children to teach them?” asks Ravi Aladangiri, a 51-year-old jockey. Kadamba admits that the use of the whip is forbidden, though it had been informally decided to limit it to three strikes per race.“Our latest investigations at kambalas held this season revealed that reluctant, scared buffaloes were whacked repeatedly with bare hands, slapped in the face, kicked and hit with wooden sticks, and dragged to the starting point by groups of five or six people. Organisers at Dakshina Kannada, Udupi, and Kasargod events had reportedly claimed that buffaloes would be hit only with wooden sticks covered with foam or fibre. They were actually struck with uncoated sticks,” says Valliyate.

Gowda with his prizes. (Express photo by Nirmal Harindran)

Gowda with his prizes. (Express photo by Nirmal Harindran)

Gowda is not an alpha male out to tame his beasts; he speaks, instead of his rapport with them. “I love all buffaloes. Even the ones that don’t run with me. They listen to me.” What if they refuse to run? “We look after them, no? We have trained them, no? So, when we go to the starting line, they know what to do. Even the angry ones.”

The finishing line at the kambala race offers a glimpse into this see-saw between man and beast. As the bulls charge in, men wave their hands, trying to calm them down in a gesture that might be a blessing or a prayer. Sometimes, it takes a team of able-bodied men to break their momentum; sometimes, the jockey launching into a blood-curdling yell stills them.

It is Gowda’s turn. He is running a challenging race, with his trusted Kaala and Pandu. Together, the three hurtle towards the line in a splash of mud and water. The nagarbetta makes a sharp contact: 135 m in 12.55 seconds. The bulls careen to the end, about to ram into the crowd, not quite yet in control. Gowda’s eyes flash, summoning a rage that we hadn’t seen before. He raises his hand at the buffaloes. They flinch, and back off.