Anju Dodiya at Chemould Prescott Road Gallery, Mumbai.

Anju Dodiya at Chemould Prescott Road Gallery, Mumbai.

Mumbai-based Anju Dodiya is among India’s best-known contemporary artists and a two-time nominee for the Sotheby’s Prize for contemporary art. Her latest, and 19th, solo exhibition, “Breathing on Mirrors”, currently showing at Gallery Chemould Prescott Road, Mumbai, brings together watercolour and charcoal paintings on her signature “mattresses” (made with fabric on a padded board), and digital works. A female protagonist, sometimes androgynous, dominates the paintings. Versions of this figure, depicted in strong chiaroscuro, draped in robes or tunics, have inhabited Dodiya’s frames for years. Ahead of the opening, the artist, 55, speaks about resisting gendered readings through her craft and why the creative process is essentially a violent one.

Excerpts:

You bring up the idea of the mirror often in your works — your first site-specific installation, Throne of Frost, which used mirror shards. Does the exhibition title refer to these ideas?

As a student, I used the mirror to draw myself, as a daily nocturnal diary, partly because there was no other model available. Slowly, as my work developed after my first exhibition (in 1991 at Gallery Chemould) I created a self — not my self, but an artistic self. It was not a private autobiography. It was either about the creative process or narratives built around the so-called self. The mirror started there and then I worked without it. Throne of Frost, in 2007, was a reference to the idea that I paint with the self-image. But, you create a mountain and yet you can never escape the beginning. You are always referred to as the artist who does self-portraits.

As an artist who has stood your ground with painting for 30 years, have you ever been told that painting is old school?

Since Day 1, I have been told that painting is a conventional art — the whole ‘painting is dead’ thing. There have been situations when one has been humiliated on that count and I remember feeling defensive about it earlier. Over the years, there has been a greater clarity that this is what I do and that there are possibilities of pushing the limits. Certain arts, like performance, are newer and their history is shorter. In that context, painting becomes more difficult.

My daughter Biraaj studied at New York University and the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. When (husband and artist) Atul and I asked her what she thinks about painting, she said, we are coming from a narrow point of view, that even video is old hat.

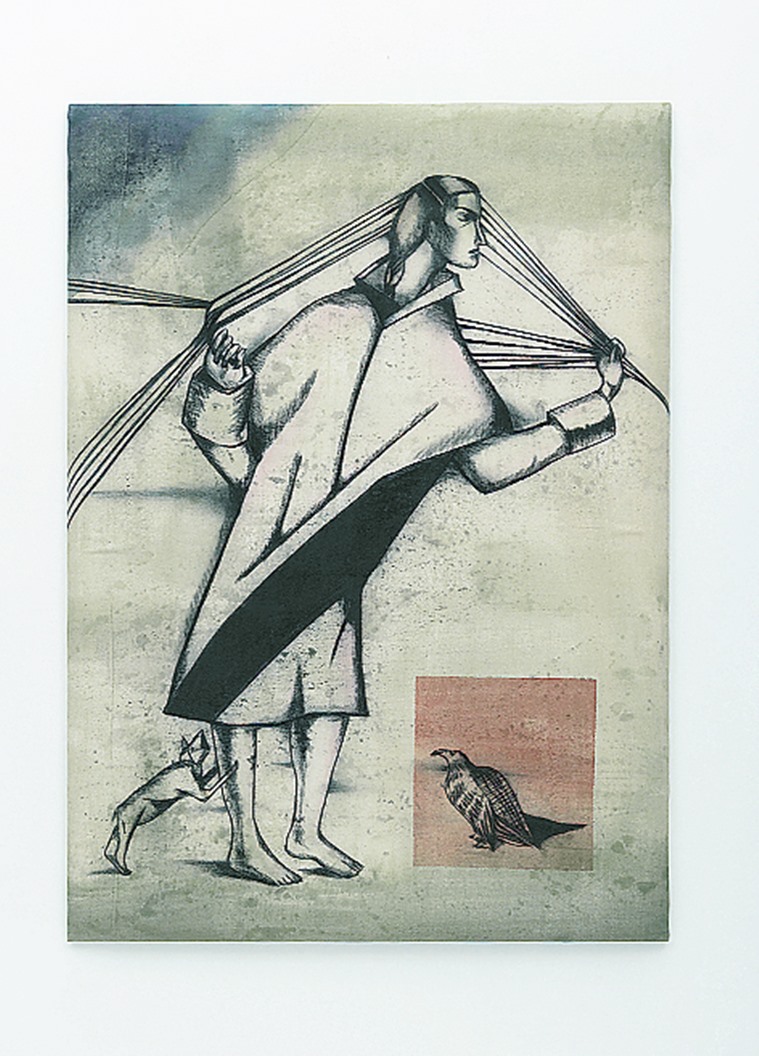

Arachne’s Walk(2019).

Arachne’s Walk(2019).

You have often referred to Western art history, particularly pre-Renaissance artists by way of titles or the figuration. Do they interest you more than Indian art history?

Pre-Renaissance artists such as Piero della Francesca and Giotto di Bondone interest me because there is a certain simplicity to the figuration. They haven’t moved into realism yet, the subject matter is given — it’s the story of Christ, mostly — and there is emotional intensity.

After (graduating from) the Sir JJ School of Art (in Mumbai), Atul got a scholarship to be in Paris for a year. We visited (artist) Gulammohammed Sheikh before leaving and he had suggestions about what we should be doing with our time. My interest developed because he spoke of an extensive list with specific names and frescoes.

A number of Indian artists one has admired, such as Sudhir Patwardhan, Gieve Patel or Akbar Padamsee, have often connected with Italian painting. I don’t have to justify my connections to certain kinds of art. The direct question would be: Why don’t I paint like Sudhir? Most people forget that art is not about ‘what’ but about ‘how’. It’s not about painting a fort that looks like a fort but to show, say, entrapment.

In spite of an abundance of female figures, your paintings have mostly resisted gendered readings. What are your thoughts on the female body becoming the tool through which women’s art and their feminism get understood?

Many years ago, I would say, ‘Of course I am a feminist, you don’t even have to discuss it.’ I took feminism for granted, I have a daughter, I work with women gallerists — but I find that in the last few years, the tables have turned. Maybe it is time to talk again. Especially now, for, whatever little we have, maybe snatched away, just like the political situation we are in.

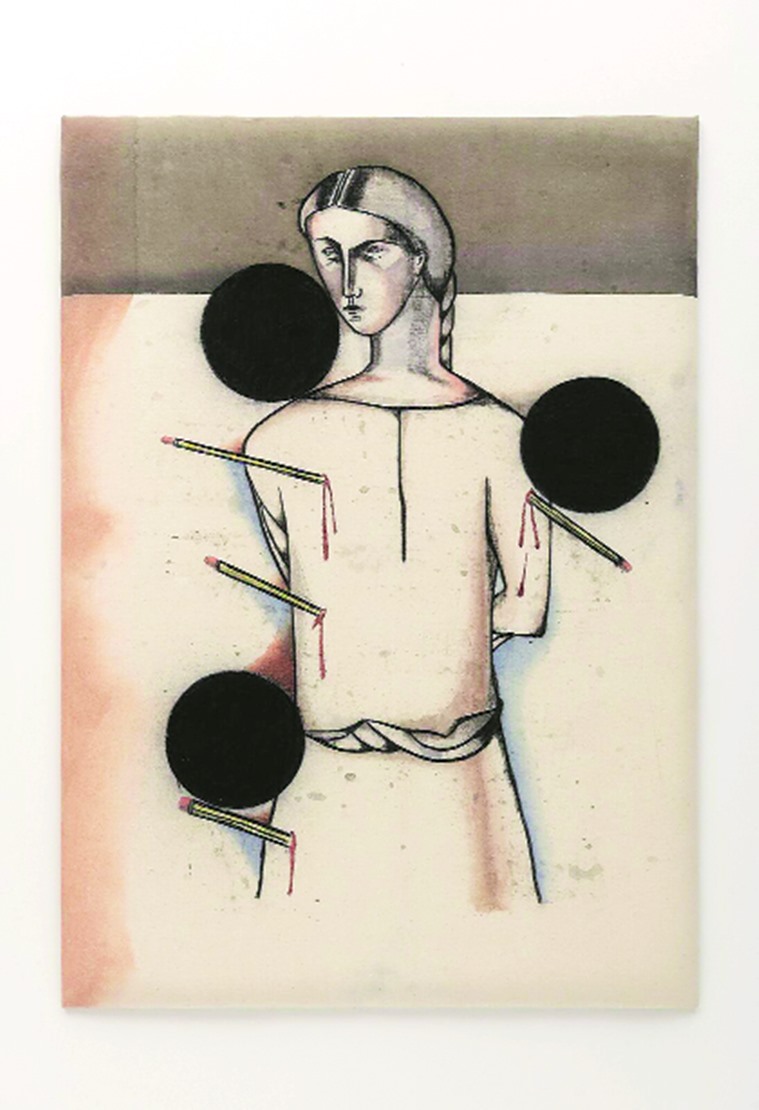

Target (2019).

Target (2019).

Artist Subodh Gupta recently made an out-of-court settlement in a defamation case against anonymous allegations of sexual misconduct against him. What are your thoughts on this?

It’s a difficult question for me because Subodh is a friend and I also side with the #MeToo movement. The question of the anonymity of the victim is an issue. I am not talking about this case — but how does one speak up without the veil of anonymity? There could be many reasons and it’s a terrible thing (that has surfaced) in various complaints. At the same time, it weakens the voice of the victim, not legally, but because you are not sure.

In general, I find that men have been extremely irresponsible and they need to wake up. Even their very gestures (body language) come from a position of power.

In several works, charcoal sticks or pencils pierce the figure. Do you think the creative process is essentially a violent one?

In a sense, if you are a creative person or a writer, you may love what you do but that is your area of assault. It’s something that makes you and unmakes you. I have to face the white of the canvas, there has to be integrity and great rigour, and that implies violence because you are pulling ideas from your head. Thinking is a violent process. Creativity is a violent process because you are structuring something out of nothing. We are talking about interior violence, but, of course, there is so much going on with the world right now.

I am in the studio making all these images and it’s not real pain. It’s not heroic at all. One wants it to be but it isn’t. It is nothing compared to what you see happening outside, happening in Delhi just now.

The wall text in your ongoing exhibition quotes from poet Rainer Maria Rilke’s poem Go to the Limits of Your Longing. You have earlier titled one of your exhibitions, “The Air is a Mill of Hooks” (2018), after a line from a Sylvia Plath poem. How has poetry influenced your art practice?

With Rilke, you can go on forever — the idea of beauty and terror, and letting it all happen to you. I always wonder at the constancy with which he can delight me. With Plath, I look at the structuring of pain. I also read a lot of Anna Akhmatova. The digital prints in this exhibition are named after a line from a TS Eliot work. It’s got to do with the passing of time, about mortality and the mundane, and is connected to the installation. I read poetry in bits and parts. I deal with fragments. I read it for pleasure but in a consistent way and read it only in the studio. The time for fiction is bedtime.