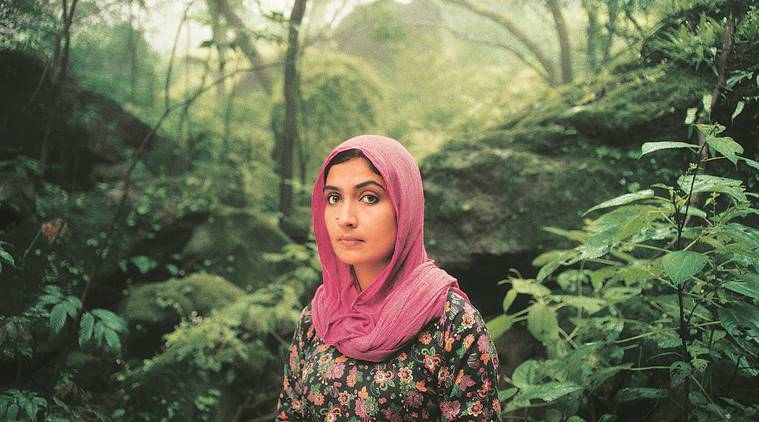

Laila Aur Satt Geet premiered at Berlin International Film Festival 2020. (Express)

Laila Aur Satt Geet premiered at Berlin International Film Festival 2020. (Express)

Pushpendra Singh’s Laila Aur Satt Geet (The Shepherdess and the Seven Songs) tracks the ancient migratory ways of a nomadic tribe, to craft a stunningly lyrical, layered, sharply political and strikingly feminist work of art.

Singh’s film, which premiered at the just-concluded Berlin International Film Festival, is a continuation of the filmmaker’s exploration of the past and present, of mining new meaning in old myths, and how stories and spaces shape us. His previous work has shown at major festivals (Lajwanti was in Berlin in 2014 ; Ashwatthama premiered at Busan in 2017; Maru Ro Moti premiered at MAMI, Mumbai). This return to the Berlinale is a circling back to his happy place.

Set in the Jammu and Kashmir valley, Laila Aur Satt Geet draws inspiration from a 14th century mystic Kashmiri poetess called Lalleshwari, and a short story by Vijaydan Detha. A young shepherd’s entrancement with the lovely Laila leads to marriage, but her beauty draws other men as moths to flame. The film deals with the consequent turmoil at several levels among the couple, the community, and the interlopers — the definition depends on which side you stand.

It works as the thing itself, a story of love and longing, irradiated by the terror and beauty of illicit and complicit desire. And a parable, speaking to the current happenings in the valley: the uneasy power structures we see at play between the security forces at the borders who demand ‘identity papers’ (‘kaagaz’) and the wandering herdsmen and women, are almost prescient of things to come.

On a rainy Berlin evening, Singh, 42, speaks about the making of the film, and what it means at a time when India is struggling with rising polarisation and communal discord. And offers a stab at resolution. Excerpts from the interview:

What got you interested in telling this tale?

I have been fascinated with the migrations of the Bakarwal-Gujar community in Kashmir since childhood. Much later, I read a piece (in The Indian Express) about how cow protectors were impacting their journey, and I knew I had to set my film there. To make it contemporary, I turned the feudal lords (in the short story) into the security forces, one being from the police, the other the forest ranger, both of whom are attracted to Laila.

They (the tribespeople) speak a very interesting language, which is a good example of Indian diversity — a mix of Rajasthani, Punjabi, Dogri and Urdu. It is something we need to hear, especially now that there’s so much talk about one desh, one language, and one culture.

Still from Laila Aur Satt Geet

Still from Laila Aur Satt Geet

That is why it (the film) is so political.

Yes, it’s subversive, and very, very political in the way I have used the whole Kashmir situation. Laila for me represents Kashmir, and the forces—one is the Indian state, the other the Kashmiri side. And I’ve also used the way the Kashmiris exhibit the Stockholm syndrome, sometimes with the Indian state, sometimes with the separatists.

And that’s why Laila keeps reaching out, and then contriving to back off.

Yeah, it’s all about what’s in play. The Indian state has one play, the state government has another play, then suddenly one day they remove (Article) 370, and the whole play collapses. It’s a new game now. We have to be very afraid of these people, they are making things that looked impossible, possible.

It’s quite interesting how the film resonates globally.

The first thing I ask myself when I begin writing is why do I want to make this film. I saw how migration is happening everywhere, Syria especially. That’s why I brought it all in — the themes of migration, boundaries, states, nations, and identities.

Pushpendra Singh, Director of Laila Aur Satt Geet.

Pushpendra Singh, Director of Laila Aur Satt Geet.

And a very spiritual streak to bind it all?

Yes. Even in the 14th century, there was conflict. Kashmir was going through a lot. Buddhism had disappeared, Hinduism, especially Shaivism, was on the rise, Islam was coming. So were the Sufi orders. I thought of spiritualism as a solution for conflict everywhere, for today’s Kashmir also.

When you say ‘solution’, what exactly does that mean?

I feel the whole idea of borders is redundant, and this whole idea of religion, especially radical, has to go away. If we promote spirituality and keep spiritual traditions alive, I think we can find peace. Within and among ourselves.

Doesn’t that sound too idealistic, given our times?

I don’t think so. We’ve always had spirituality in India. Look at the Sufi tradition, which came from Iran, but became ours. Look at the whole Kabir tradition, the Kabirpanthis… Where conflicts are intractable, spirituality will show the path.