Farmers crowding at a cooperative bank branch in Maharashtra. (Express Photo: Arul Horizon)

Farmers crowding at a cooperative bank branch in Maharashtra. (Express Photo: Arul Horizon)

Ashok Raghunath Patil has, for almost a decade now, stopped taking any ‘peek karj’ (seasonal agricultural operation loans) from the Bhimrao Anna Multipurpose Cooperative Society that’s right in his village. Instead, he has been borrowing — to finance cultivation of sugarcane on four acres and seasonal vegetables such as tomato and cucumber on the remaining four of his eight-acre holding at Kameri village in Sangli district’s Walva taluka — from the Bank of Maharashtra. This is despite the public sector commercial bank having its branch at Islampur town, which is about 5 km from his village.

“I prefer going there. The officers and staff are more professional than the people in the society here,” states Patil, who has been dealing with Bank of Maharashtra since 2011. The bank advances him working capital (“scale of finance”) at the rate of Rs 40,000-45,000 per acre for his sugarcane crop. This loan, extended 1-2 months before plantings (which happen in June-July for the 18-month adsali and November-December for the 14-month pre-seasonal crop) and repayable over one year, attracts an annual interest of 7%.

Back in 2011, Patil was the only one in Kameri, who chose to bypass the local credit society, through which the Sangli District Central Cooperative Bank (DCCB) disburses crop loans, in favour of a scheduled commercial bank. “But today, many of my relatives and friends within the village have moved to the Bank of Maharashtra,” says the 60-year-old, who has also availed a Rs 3 lakh seven-year loan at 12% interest from the same bank to install a drip irrigation system for his sugarcane fields.

Patil represents a growing number of farmers in Maharashtra who no longer rely on the cooperatives, which have traditionally dominated the state’s rural lending landscape (especially for crop credit), for fulfilling their financial needs.

Aggressive penetration, better customer service and deployment of technologies such as mobile app by commercial banks — both public sector and private — have led to their gaining market share at the expense of cooperatives. The relative absence of politics — sanctioning of loans not being a function of proximity to directors in the DCCB/credit society board — is an additional factor cited by farmers for choosing commercial banks.

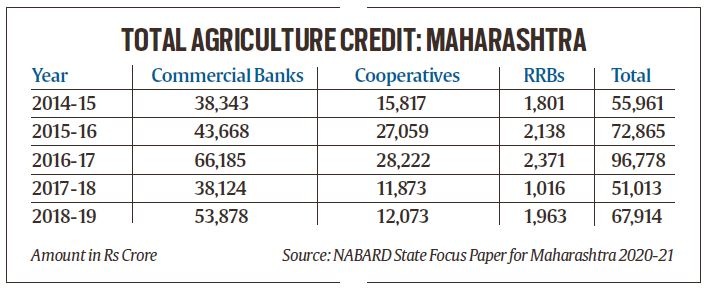

Evidence for the above migration can be seen from the accompanying table. In 2014-15, cooperative banks accounted for

Rs 15,817 crore or 28.3% of the total agricultural credit disbursed in Maharashtra. By 2018-19, their lending had fallen both in absolute as well as relative terms to Rs 12,073 crore and 17.8%, respectively. One reason for that was the increased share of term loans (from Rs 21,860 crore in 2014-15 to Rs 36,677 crore in 2018-19) in the total agricultural credit (Rs 55,961 crore and Rs 67,914 crore, respectively for these two years). Commercial banks have practically taken over the term-lending segment.

Before any new crop season, farmers take loans from cooperatives, commercial banks and regional rural banks (RRB) to finance their input (seed, fertilisers and pesticides), labour, irrigation and energy requirements. The normal interest rate on such ‘peek karj’ is 7%. In case of timely repayment, farmers are entitled to an interest subvention of 3% from the Centre and 2% from the state government. That makes the effective interest rate at just 2%.

Commercial banks require farmers to provide their ‘7/12’ land revenue extracts and have two guarantors each time that they apply for a crop loan. If the loan is for cane cultivation, they have to additionally furnish a copy of the agreement signed with the sugar mill for offtake of the crop. The DCCBs, on the other hand, deal not with individual farmers, but village-level societies (such as the Bhimrao Anna multipurpose cooperative) that draw up the necessary agreements with mills and arrange for guarantors on behalf of their members.

“With commercial banks, I can approach them directly and they will pass the loan application if my papers are right. With cooperatives, you have to be in the right camp and they also take their own time to process the application,” claims Patil. Maharashtra has 21,102 primary agricultural cooperative societies affiliated to 31 DCCBs. The directors on their boards are elected from its members, which also makes these bodies vulnerable to political headwinds.

Latest data from the National Bank for Agriculture and Rural Development reveals that commercial banks currently have 2,761 rural branches in Maharashtra, which is higher than the 2,761 of DCCBs and 444 of RRBs. Even among the 31 DCCBs, only 8-10 are believed to be financially strong to sustain credit growth.

“The ones that are still alive are struggling to remain relevant as commercial banks are looking to increase their physical presence and offering better services. And rural banking is not just limiting yourself to agriculture,” points out a cooperative bank official based in Pune.

Take the relatively better-performing Sangli DCCB. In 2018-19, it made crop loan disbursements of Rs 1,304.95 crore, as against Rs 1,022.43 crore the previous fiscal. However, Mansing Patil, general manager (banking and loans), is visibly worried. “Yes, there is year-on-year growth, but our customer base isn’t increasing. The younger rural folk are turn to commercial banks that provide better technology-based solutions,” he admits.

Between 2016-17 and 2018-19, the DCCB has seen the number of loanee farmers attached to its 4,133 village societies shrink from 1.66 lakh to 1.43 lakh. The 92-year-old bank is at present facing problems due to four out of the region’s 17 sugar mills defaulting on loans given by it. “We are keen to introduce mobile banking, but the Reserve Bank of India has not granted permission because of our high non-performing assets, which touched 11.83% (of gross advances) at the end of 2018-19,” he adds.

Over-dependence on crop loans and lending to agri-based industries is another issue. The Islampur-headquartered Rajarambapu Sahakari Bank operates 33 branches that are largely in the peri-urban and rural areas of Sangli, Kolhapur, Satara, Pune and Solapur districts. This cooperative bank lends to farmers as well as micro, small and medium enterprises in these areas. According to its managing director Rajaram Jakhale, over 51% of the bank’s

Rs 1,489.80 crore loans disbursed last fiscal was for housing, MSMEs, vineyards, drip irrigation and other long-term agricultural investments. “But we cannot easily compete with commercial banks. They have access to much cheaper funds and are offering home loans at 8-8.5%, whereas we can give only at 9.5%,” he notes.

For the farmer, whose loan needs now go beyond agriculture, the choice is clear. Pravin Patil, 40, owns eight acres at Bahe village in Sangli’s Walva talika, on which he grows sugarcane in four and soyabean and groundnut in the rest. “I go to the cooperative society only to avail crop loan. But for other needs, I prefer either Union Bank of India or the Bank of Maharashtra,” he declares. And he doesn’t mind going the extra distance to Islampur.