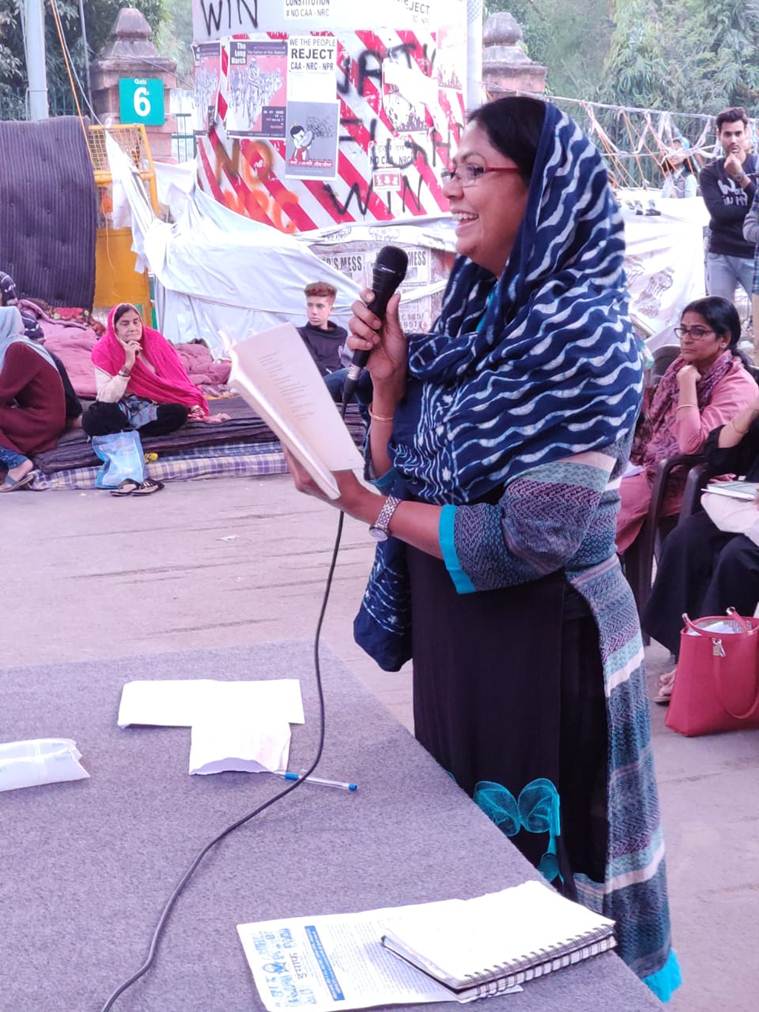

Mamta Sagar, Anitha Thampi and Salma at the Jamia protest site (Express Photo)

Mamta Sagar, Anitha Thampi and Salma at the Jamia protest site (Express Photo)

Outside the Jamia Milia Islamia University campus, a few hundred metres from where a gunman opened fire last month, protesters Monday gathered near gate number 7, to listen to three renowned women poets—Mamta Sagar, Salma, and Anitha Thampi.

In solidarity with those holding a sit-in against the Citizenship Amendment Act, the NPR and the proposed NRC — even as students went about their usual classes — the three poets used art to talk about resistance. Despite the language barrier, the meaning wasn’t lost.

Mamta Sagar, a Kannada poet, Salma, a Tamilian, and Anitha Thampi from Kerala enthralled the audience with their recitations. The three poets also happen to be friends and had been planning to travel and “have fun” for the past 10 years. “We didn’t expect it would happen this way,” Anitha said.

“We are leaning on the Constitution as a backbone,” said Mamta. “Our generation has seen all kinds of protests — Dalit movements, women movements, protests by the marginalised, LGBTQ movements. The Constitution talks of diversity. It is, after all, about inclusiveness,” she maintained.

Invoking Periyar, Salma sang Path and Closer, translating every stanza in English (Express Photo)

Invoking Periyar, Salma sang Path and Closer, translating every stanza in English (Express Photo)

Salma, who had faced virtual imprisonment by a conservative family since she was 13, has long fought for women rights, seeking to break taboos and stereotypes in her work. She is currently a member of the DMK. Her contribution to Tamil literature as a woman Muslim poet who fought her way to freedom is well documented, and her two books of poetry — Oru Maalaiyum Innoru Maalaiyum (An Evening and Another Evening) and Pachchai Devathai (Green Angel) — have established her name in the literary circles of India.

“Bertolt Brecht wrote poems about the dark times. These are the dark times,” she said. Expressing her unwavering support to the protesters, she asserted “art is always political.”

“When artists love and care about their society, they write about it. This time, artists have joined the people who are fighting for their land, for democracy. Like us, they love their country,” she said.

Invoking Periyar, Salma sang Path and Closer, translating every stanza in English. Before she began to sing, she emphasised: “Tamil Nadu is with you.” The DMK leader also assured the protesting crowd of her party’s support.

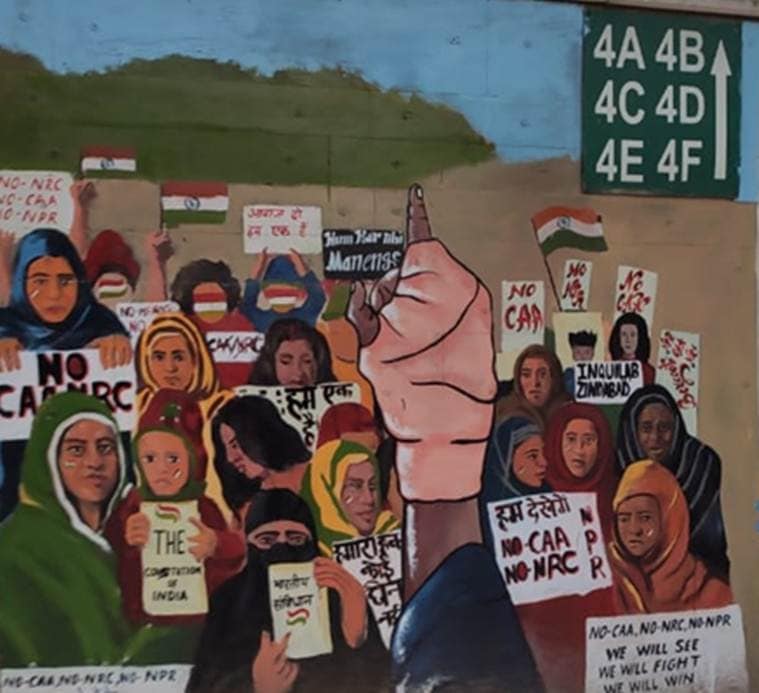

Women have been at the forefront of anti CAA protests, as represented here in a graffiti outside the university campus (Express Photo)

Women have been at the forefront of anti CAA protests, as represented here in a graffiti outside the university campus (Express Photo)

A round of applause later, Anitha, whose first book Muttamatikkumbol (Sweeping the Courtyard), has been translated into various languages within and outside of India, recited her Malayalam poem Illah, and The Lost Needle.

Anitha confessed she had never before explicitly confronted politics in her work

Anitha confessed she had never before explicitly confronted politics in her work

Anitha confessed she had never before explicitly confronted politics in her work. “That is because I could afford to do it,” she explained, “thought the act of writing in itself is political, even if it is meditative writing or personal.” But “that was until now”.

“The times have changed. Every time there is an instance of violence, we pinch ourselves to believe it. Every time, we think this is an exception, and it boomerangs. But artists cannot keep silent anymore. We have reached a point where we are being forced to speak out loud,” she said.

Mamta Sagar castigated ‘religion that divides us’ in a thought-provoking poem ‘Dharma adharma in the house’. “Religion can never take the frontline in this country. Caste is a problem, we never address that. Religion divides people,” she said.

“Art has often been misunderstood, and has also maintained its eliteness. There has been a gap between the masses and producers of art. But history has it that literature has thrived wherever it has mingled with the masses, like Karnataka’s Vachana movement against hierarchy in the 12th century — the hierarchy that is created by dharma. Only art that is connected through the times sustains,” she said.

Mamta’s tribute to slain journalist Gauri Lankesh in a set of poems titled For Gauri and her translation of Faiz Ahmad Faiz’s Hum Dekhenge into Kannada reverberated in protests held against the Citizenship Amendment Act in Karnataka. The same could be seen at the Jamia protests.

Mamta Sagar castigated ‘religion that divides us’

Mamta Sagar castigated ‘religion that divides us’

The three poets together ended their poetry presentation by with Faiz’s Hum Dekhenge in Urdu overlapped with Kannada, Tamil and Malayalam versions of the same.

The protest in Jamia broke away with binaries and barriers. Women took centrestage, no longer just footsoldiers in their fight against the government’s new law; artists — women again — sang in Kannada, Tamil, and Malayalam to a mainly Hindi-speaking crowd, as people from all religions stood in support.

“The voices of violence have always used language to portray lies as truths and dismiss the historical resonance of everything. Language is a tool of resistance. The freedom of language can transform the country,” said Anitha.

When asked if she sees hope, Salma welled up. “I want to but I don’t think so.” “But hope is why we are here, why everyone is here,” Anitha and Mamta said emphatically. “We are clinging on to hope, and we will,” they said.