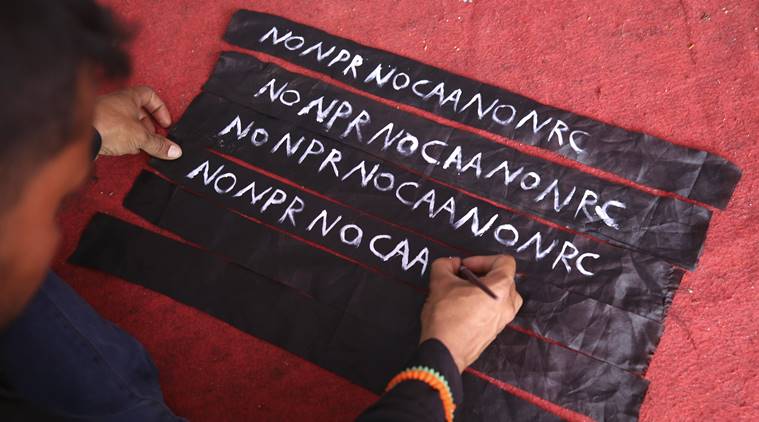

At a protest in Bengaluru on February 12, 2020. (AP Photo: Aijaz Rahi)

At a protest in Bengaluru on February 12, 2020. (AP Photo: Aijaz Rahi)

The standard defence of the CAA being trotted out by the BJP’s “outreach” programme is the claim that the rights of no existing Indian citizens will be affected. The most recent instance of this “reassuring” claim is the letter to the “grandmothers” of Shaheen Bagh by Firoz Bakht Ahmed, (‘ IE, February 21). This claim, particularly when seen in conjunction with the NPR — due to start on April 1 — and the still-shadowy NRC, is almost certainly false.

Of course, it may also be technically/legalistically true. After all, if all that was being proposed was a faith-based denial of citizenship to some refugees, people who are already “Indian citizens” would be exempt from its purview. Of course, whether or not they are “Indian citizens” would be subject to the determination of the NPR/NRC. And when the CAA helpfully removes some of those deemed “non-citizens” from the category even of eligible refugees — well, the “non-existent” detention camps will accommodate them. To say further that the CAA is only conferring rights on some refugees is beneath contempt — because even a child knows that a selective conferring, whether of sweets or citizenship, is implicitly a denial for the ones who are excluded.

If, on the other hand, we are to take the prime minister at his word — that the NRC has not been so much as a gleam in the government’s eye — then what are we to make of the home minister’s oft-repeated threat — ghar-ghar mein ghus ke maarenge?

The official defence of the CAA, the reassurance given to Indian Muslims, is that the law is only concerned with the rights of others — potential refugees from neighbouring countries — and that consequently their rights are unaffected. This very reassurance, even beyond its likely falsehood, exposes the moral emptiness of the ruling dispensation. Because, plainly speaking, a concern with the rights of others is fundamental to being a moral, morally engaged person. After all, even dogs bark — as dog-whistlers must know. Rats squeal. Speaking — barking, growling, squealing — in defence of one’s self-interest is something we share with the rest of the animal world. Human, humane moral conduct begins where mere self-interest falls off. People must learn to become human — to be concerned with the rights of others, to be capable of sympathy and empathy, beyond the domain of individual or collective narcissism. And mature societies create institutions — families, schools — in which children learn what it means to be human. Or, on the evidence of the violent adults swarming our streets, fail to learn. Learn elsewhere. Because, of course, the extremes of both human altruism and human monstrosity are unknown in the natural, animal world. Both Mother Teresa and the lynch-mobs are uniquely human phenomena.

One of the many bizarre things one heard about the conduct of the Muzaffarnagar police was the report that they had charged some parents under some juvenile protection act because the parents had brought their children with them to attend a protest against the CAA — even though, clearly, their rights were unaffected. Indeed, the children might have been too young to even understand what rights mean — rather like the UP police, in fact. And of course, given that the UP police were there, the children could easily get hurt, right?

At about the same time that this curious story about the concern of the UP police for children’s rights appeared, my daughter sent me a picture of a small anti-CAA demonstration in Oxford: Some 40-odd people, standing on the cobbles outside the Radcliffe Camera, shaking their fists in protest in the winter air. And there, part of the conscientious gaggle of protestors, was my elder grandson, blowing away on his trombone, a musical accompaniment to the demonstrators’ slogans. And my younger grandson, not yet five, looking baffled, standing beside his mother. Alas, he wasn’t up to understanding the intricacies of the CAA, but he still picked up a crucial cry — Inquila’ Zindaba’! Of course he doesn’t understand what it means, but one day he will. And meanwhile, he will have learnt an important moral lesson: It is a concern for the rights of others — unknown, distant others — a willing to undergo some discomfort and, in Muzaffarnagar, some danger too — that makes us human, humane beings. So, honourable (and dishonourable) apologists, please desist — I speak not merely although my rights are unaffected, but even because my rights are unaffected.

And yet, strictly speaking, that’s not even true. I have a constitutionally guaranteed right to my country, a right — indeed, a responsibility — to be concerned about my country, and about the fate of my country. That right supersedes any alleged “mandate”, and is rooted in the democratic Constitution of my country.

The Constitution is not simply a document. Grammatically speaking, it is the record of an act and a process, a heroic endeavour of self-making through which, in the midst of a million difficulties, the Republic of India was created — democratic, secular, socialist, committed to principles that were spelt out in the Preamble. It is to the Preamble that we turn to remind ourselves of who we were, and what we set out to become, in that blood-stained moment, over 70 years ago.

So if the Sangh Parivar wish, now, to create a new kind of India then they will have to begin at the beginning: Convene a new Constituent Assembly, and let’s see if we can agree on another viable India. But if we should fail, the responsibility for that failure will rest squarely on their shoulders, who have, patiently and assiduously, worked to hollow out and undermine the Constitution. Writing in The Guardian, the novelist Amit Chaudhuri expressed with clarity and eloquence what is at stake in the deceitful phrasing of the CAA, as well as in its devious concert with the NPR and the “as-yet-undiscussed” NRC: “What’s being put to death here with the omission of a single word is what it means to be Indian: part of a fraught but great experiment that has no parallel anywhere in the world. Every Indian has contributed to creating India, and we — not just Muslim refugees — are suddenly being denied access to what we’ve created.” So.

This article first appeared in the print edition on March 4, 2020 under the title ‘The rights of others’. The writer taught at the Department of English, Delhi University and lives in Allahabad.