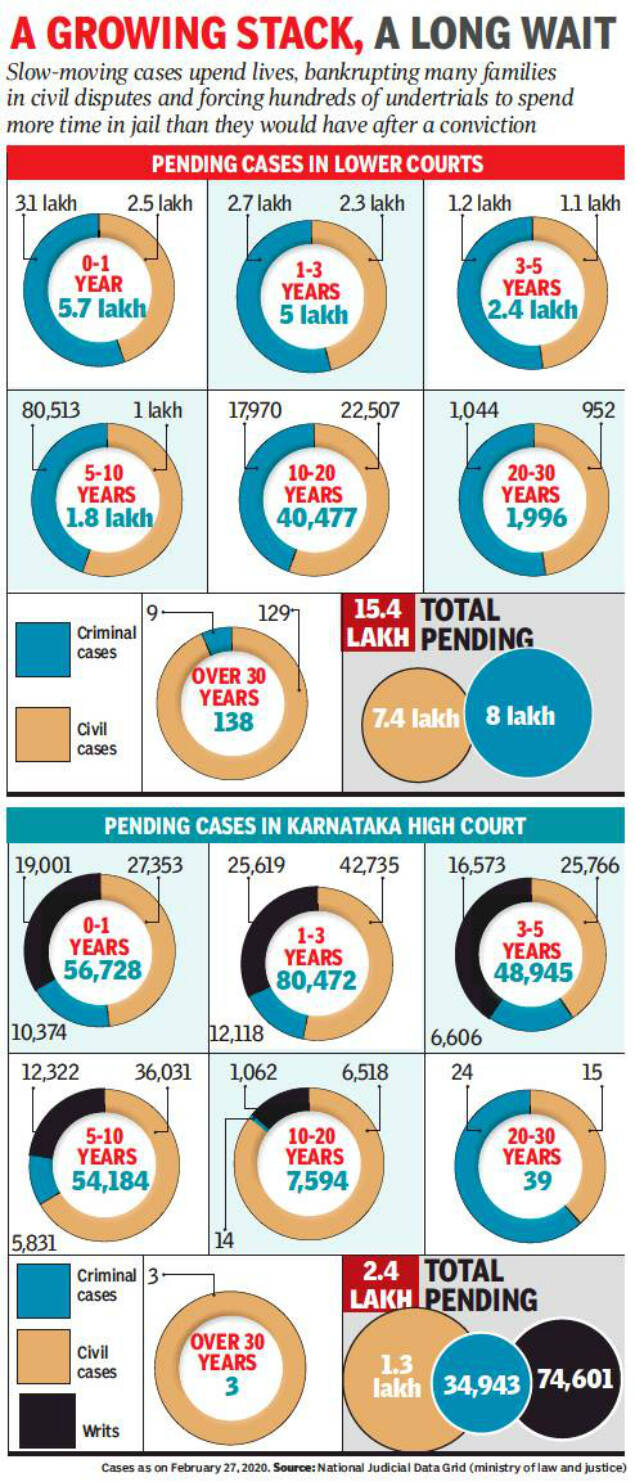

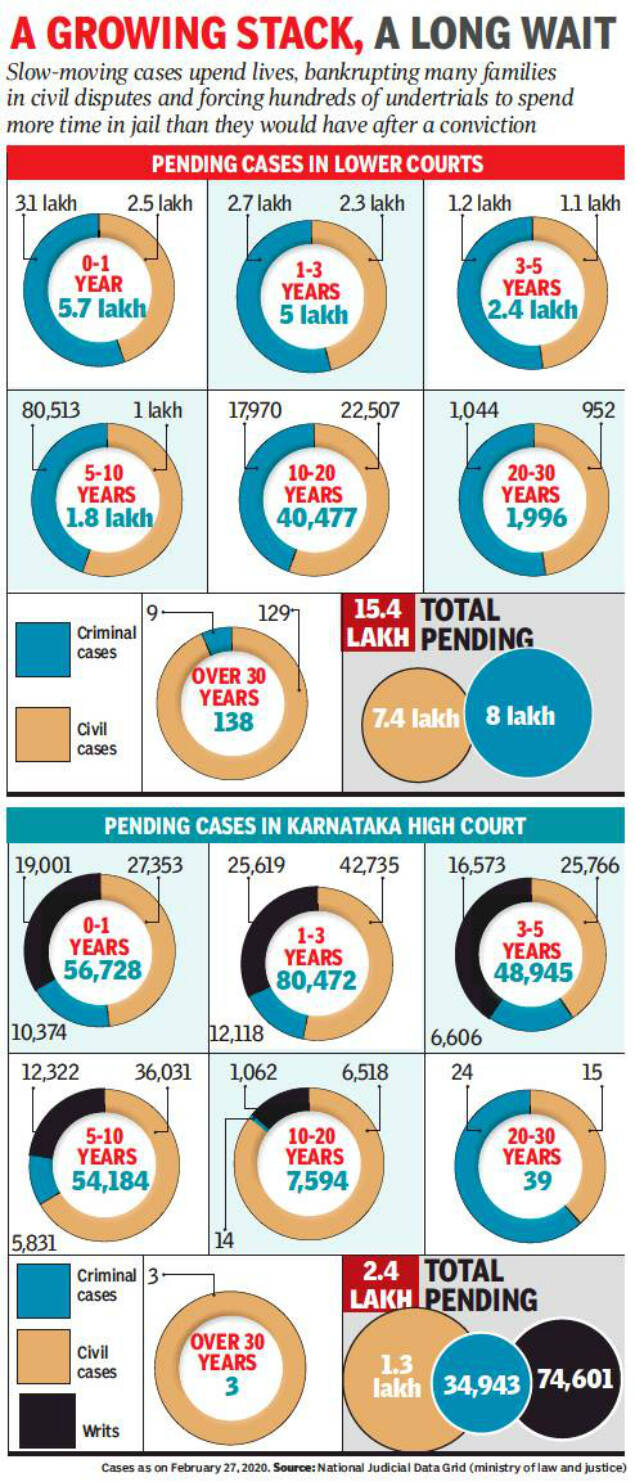

BENGALURU: Unlike wine, court cases don’t age well. The more they grind on, the more despair they bring for people hoping for a fair or reasonable outcome. Courts in Karnataka have more than their share of such cases. As of February 27, 2020, the backlog stood at nearly 18 lakh.

To put it in perspective: even if every judicial officer and judge of lower courts and the high court works for 365 days without a single leave, they will still have to dispose of at least five cases daily to clear the mountain of pending matters.

Add to this the number of new cases filed every month, and the task only gets more complicated. In January this year, 6,355 fresh cases — on average, over 200 every day — were filed in the Karnataka high court alone. Lower courts also receive hundreds of new complaints, applications and petitions daily.

Activists say slow-moving cases upend lives, bankrupting many families in civil disputes and forcing hundreds of undertrials to spend more time in prison than they would have after a conviction.

“The system has given a false hope to the litigants that even if they fail, they can take advantage of the long-drawn process, which leads to speculative litigation. That is, even if a litigant knows there’s no case, they move courts to harass the opponent. In my view at least 50 per cent of the cases are speculative,” former Supreme Court judge Santosh Hegde told TOI. “...if we have to reduce pendency, the government and the Supreme Court must sit together and come to consensus on how to go about reducing the number of appeals. As in the US, the high court must be the final court for all matters other than constitutional matters. In lower courts and high courts, speculative litigation must be scrutinised, and penalties must be levied.”

Of the 17.8 lakh pending cases, 15.5 lakh are in lower courts in Karnataka. The remainder are before the various benches of the high court. There are 1,104 judicial officers and judges across all courts in the state.

The high court has a sanctioned strength of 62 judges; about 36 per cent of the posts are vacant. There are 1,064 judicial officers in district and subordinate courts as against the sanctioned strength of 1,303, a shortfall of 19 per cent. While the figure of high court vacancies is current, that of lower courts was last updated in December 2019.

The individual burden of work is much higher for high court judges. To shrink the pile of pending cases, each judge would have to dispose of at least 16 cases every day for the next full year without breaks.

Karnataka (all courts put together) has the highest number of pending cases among southern states (Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Kerala and Tamil Nadu).

Of the nearly 18 lakh cases in Karnataka, 49 per cent pertain to civil matters, while 47 per cent are criminal ones. The rest are writ petitions. Thirty-three per cent of the total cases have dragged on for one to three years. While 2,035 have been pending for 20 to 30 years, another 141 have pending for over 30 years.

Twenty-one per cent of the pending cases, or nearly 3.9 lakh, were filed by senior citizens and women. A former high court judge had told TOI that while vacancies must be filled up on a war footing, one must ensure that advocates being appointed as judges had practised both civil and criminal law.

Advocate KV Dhananjay also recommended that positions of judges should be filled up and the number of appeals should be reduced. “I think we are not too far away from getting artificial intelligence in judiciary. There has been some movement in this direction in other countries. For instance, IBM has demonstrated a robot which can make live arguments using AI in the US. While nothing concrete has happened so far, we could be on the cusp of a revolution and I think India won’t lag in this aspect when there is enough evidence that technology would work,” Dhananjay said.

He said AI could help decrease the time taken to resolve cases, thereby preventing piling up of matters.

ST Ramesh, a former Karnataka director general of police, lamented the lack of progress. “There has been a lot of talk on the issue, but very little action by the government and other stakeholders. First, the ratio of judges to the population and cases must be scientifically determined. As it is, in India, many people have no access to justice and even if you look at those who have access, the ratio of judges is not enough. Second, there has been a delay in digitisation in the judiciary. These issues must be addressed,” he said.

Every section of the system — police, forensics, courts — must be connected and the method to deal with cases should change, he said.

“Not all the fault is with the judiciary. Police and prosecutors must also understand that some cases do not merit time in the court, and they must be firm on making decisions in such matters,” he added.

To put it in perspective: even if every judicial officer and judge of lower courts and the high court works for 365 days without a single leave, they will still have to dispose of at least five cases daily to clear the mountain of pending matters.

Add to this the number of new cases filed every month, and the task only gets more complicated. In January this year, 6,355 fresh cases — on average, over 200 every day — were filed in the Karnataka high court alone. Lower courts also receive hundreds of new complaints, applications and petitions daily.

TimesView

The numbers are staggering, laying out an incontestable case for reforms, which have not moved very far from the debate circuit. Not just in Karnataka, courts across the country are grappling with a huge backlog of cases, a problem which causes unimaginable anguish to citizens seeking justice and resolution. It’s understandable that courts are cautious about embracing technology, whose use in courthouses and their processes around the world has been mostly experimental. But there are some steps which can be taken promptly: ensuring the sanctioned strength of judges and judicial officers and preventing cases with no merit from clogging up the system.

Activists say slow-moving cases upend lives, bankrupting many families in civil disputes and forcing hundreds of undertrials to spend more time in prison than they would have after a conviction.

“The system has given a false hope to the litigants that even if they fail, they can take advantage of the long-drawn process, which leads to speculative litigation. That is, even if a litigant knows there’s no case, they move courts to harass the opponent. In my view at least 50 per cent of the cases are speculative,” former Supreme Court judge Santosh Hegde told TOI. “...if we have to reduce pendency, the government and the Supreme Court must sit together and come to consensus on how to go about reducing the number of appeals. As in the US, the high court must be the final court for all matters other than constitutional matters. In lower courts and high courts, speculative litigation must be scrutinised, and penalties must be levied.”

Of the 17.8 lakh pending cases, 15.5 lakh are in lower courts in Karnataka. The remainder are before the various benches of the high court. There are 1,104 judicial officers and judges across all courts in the state.

The high court has a sanctioned strength of 62 judges; about 36 per cent of the posts are vacant. There are 1,064 judicial officers in district and subordinate courts as against the sanctioned strength of 1,303, a shortfall of 19 per cent. While the figure of high court vacancies is current, that of lower courts was last updated in December 2019.

The individual burden of work is much higher for high court judges. To shrink the pile of pending cases, each judge would have to dispose of at least 16 cases every day for the next full year without breaks.

Karnataka (all courts put together) has the highest number of pending cases among southern states (Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Kerala and Tamil Nadu).

Of the nearly 18 lakh cases in Karnataka, 49 per cent pertain to civil matters, while 47 per cent are criminal ones. The rest are writ petitions. Thirty-three per cent of the total cases have dragged on for one to three years. While 2,035 have been pending for 20 to 30 years, another 141 have pending for over 30 years.

Twenty-one per cent of the pending cases, or nearly 3.9 lakh, were filed by senior citizens and women. A former high court judge had told TOI that while vacancies must be filled up on a war footing, one must ensure that advocates being appointed as judges had practised both civil and criminal law.

Advocate KV Dhananjay also recommended that positions of judges should be filled up and the number of appeals should be reduced. “I think we are not too far away from getting artificial intelligence in judiciary. There has been some movement in this direction in other countries. For instance, IBM has demonstrated a robot which can make live arguments using AI in the US. While nothing concrete has happened so far, we could be on the cusp of a revolution and I think India won’t lag in this aspect when there is enough evidence that technology would work,” Dhananjay said.

He said AI could help decrease the time taken to resolve cases, thereby preventing piling up of matters.

ST Ramesh, a former Karnataka director general of police, lamented the lack of progress. “There has been a lot of talk on the issue, but very little action by the government and other stakeholders. First, the ratio of judges to the population and cases must be scientifically determined. As it is, in India, many people have no access to justice and even if you look at those who have access, the ratio of judges is not enough. Second, there has been a delay in digitisation in the judiciary. These issues must be addressed,” he said.

Every section of the system — police, forensics, courts — must be connected and the method to deal with cases should change, he said.

“Not all the fault is with the judiciary. Police and prosecutors must also understand that some cases do not merit time in the court, and they must be firm on making decisions in such matters,” he added.

Get the app