The World Bank’s estimates of extreme poverty — measured as .9/per capita/per day at purchasing power parity of 2011 — show a secular decline in India from 45.9 per cent to 13.4 per cent between 1993 and 2015. (Illustration: C R Sasikumar)

The World Bank’s estimates of extreme poverty — measured as .9/per capita/per day at purchasing power parity of 2011 — show a secular decline in India from 45.9 per cent to 13.4 per cent between 1993 and 2015. (Illustration: C R Sasikumar)

President Donald Trump applauded India’s achievements in his February 24 address at the crowded Motera stadium in Ahmedabad. These achievements ranged from religious freedom to reducing poverty to becoming an emerging giant economy. This should have made every Indian feel proud. However, the riots in Delhi around the same time have made us feel ashamed of our poor governance, lack of communal harmony and intolerance. But, here in this piece, we want to focus on the top three Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) of the United Nations, namely poverty elimination, zero hunger, and good health and well-being by 2030.

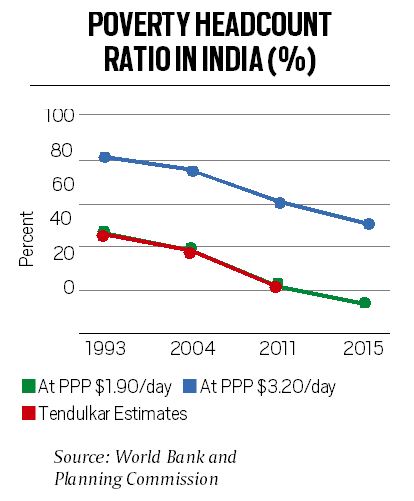

The World Bank’s estimates of extreme poverty — measured as $1.9/per capita/per day at purchasing power parity of 2011 — show a secular decline in India from 45.9 per cent to 13.4 per cent between 1993 and 2015 (See figure: Poverty headcount ratio in India).

Opinion | Parameswaran Iyer writes: Like Swachh Bharat, Jal Jeevan Mission will benefit the wider economy

If the overall growth process continues as has been the case since, say, 2000 onwards, India may succeed in eliminating extreme poverty by 2030, if not earlier. Also, given the overflowing stock of food grains with the government, and a National Food Security Act (NFSA) that subsidises grains to the tune of more than 90 per cent of its cost to 67 per cent of the population, there is no reason to believe that India can also not attain the goal of zero hunger before 2030. The real challenge for India, however, is to achieve the third goal of good health and well-being by 2030. India’s performance in this regard, so far, has not been satisfactory.

In 2015-16, almost 38.4 per cent of India’s children under the age of five years were stunted, 35.8 per cent were underweight and 21 per cent suffered from wasting (low weight for height), as per the National Family Health Survey (NFHS 2015-16). The situation in some states like Bihar, Jharkhand and Uttar Pradesh is even worse (See figure: Prevalance of child malnutrition in Indian states). No wonder, the Global Hunger Index (GHI) ranks India at 102 out of 117 countries in terms of the severity of hunger in 2019.

Source: World Bank and Planning Commission

Source: World Bank and Planning CommissionHow can India overcome this colossal challenge of malnutrition? The National Nutrition Strategy, 2017, aims to reduce the prevalence of underweight children (0-3 years) by three percentage points every year by 2022 from NFHS 2015-16 estimates. This is an ambitious target given the decadal decline in underweight children from 42.5 per cent in 2005-06 to 35.8 per cent in 2015-16 amounts to less than 1 per cent decline per year. Similar targets have been set by the National Nutrition Mission (renamed as POSHAN Abhiyaan), 2017, to reduce stunting, undernutrition, anemia (among young children, women and adolescent girls) and low birth weight by 2 per cent, 2 per cent, 3 per cent and 2 per cent per annum respectively.

Our research at ICRIER tells us to focus on four key areas, if India has to make a significant dent on malnutrition by 2030. First and foremost, is the mother’s education. It is one of the most important factors that has a positive multiplier effect on child care and access to healthcare facilities. It also increases awareness about nutrient-rich diet, personal hygiene, etc. This can also help contain the family size in poor, malnourished families. Thus, a high priority to female literacy, in a mission mode through liberal scholarships for the girl child, would go a long way towards tackling this problem.

Opinion | Rohini Pande , Charity Troyer Moore write: The budget relegated women’s economic participation to secondary importance

Second is the access to improved sanitation and safe drinking water. From that angle, the Swachh Bharat Abhiyan and Jal Jeevan Mission would have positive outcomes in the coming years. Third, there is a need to shift dietary patterns from cereal dominance to the consumption of nutritious foods such as livestock products, fruits and vegetables, pulses, etc. But they are generally costly and their consumption increases only by higher incomes and better education. Diverting a part of the food subsidy on wheat and rice to more nutritious foods can help.

Finally, India must adopt new agricultural technologies of bio-fortifying cereals, such as zinc-rich rice, wheat, iron-rich pearl millet, and so on. The Indian Council of Agricultural Research (ICAR) has to work closely with the Harvest Plus programme of the Consultative Group of International Agricultural Research (CGIAR) to make it a win-win situation for curtailing malnutrition in Indian children at a much faster pace — and, at a much lower cost than would be achieved under a business as usual scenario.

Global experience shows that with the right public policies focusing on agriculture, improved sanitation, and women’s education, one can have much better health and well-being for its citizens, especially children. In China, it was agriculture and economic growth that significantly reduced the rates of stunting and wasting among the population and lifted millions of people out of hunger, poverty and malnutrition. According to FAO, Brazil and Ethiopia have transformed their food systems: They have targeted their investments in agricultural R&D and social protection programmes to reduce hunger in the country. Despite India’s improvement in child nutrition rates since 2005-06, it is way behind the progress experienced by China and many other countries. According to the Global Nutrition Report, 2016, at the present rates of decline, India will achieve the current stunting rates of China by 2055. India can certainly do better, but only if it focuses on this issue.

This article first appeared in the print edition on March 2, 2020 under the title “Tackling the big three”. Gulati is Infosys chair professor for agriculture and Khurana is research assistant at ICRIER

Opinion | Puneet Bedi writes: Women’s health has never been an issue, not even with feminists in India, but we must make it an issue now