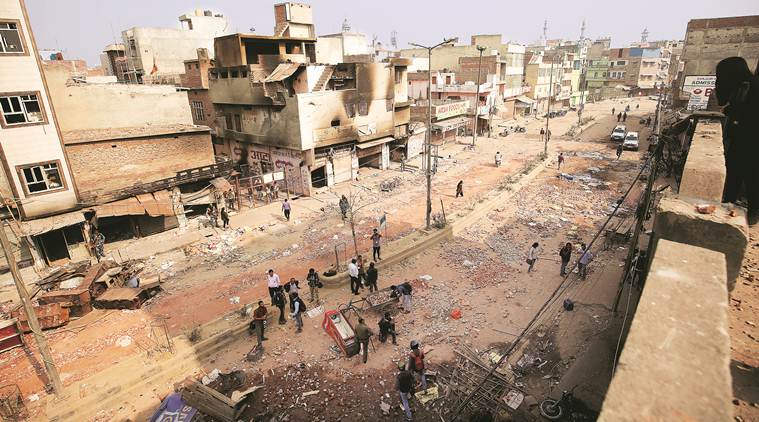

Delhi 2020 has already gone beyond Delhi 1992, even though the numbers are not yet final. (Express photo: Praveen Khanna)

Delhi 2020 has already gone beyond Delhi 1992, even though the numbers are not yet final. (Express photo: Praveen Khanna)

In the historical scale of rioting, where do the recent Delhi riots belong? And what is their larger political significance?

The first question is statistical. During early to mid-1990s, Steven Wilkinson, now teaching at Yale, and I, set up a database for all recorded Hindu-Muslim riots between 1950-1995. We did not know then that our dataset would become standard statistical reference for scholars and journalists. We simply put together the best available numbers to lend a systematic empirical base to our own books, published by Yale and Cambridge University Presses in the 2000s. Our dataset, since then, has been extended till the 2010s by younger scholars, based in the US and UK.

These statistics show that the recent riots — let me call them Delhi 2020 — are Delhi’s biggest Hindu-Muslim riots since 1950. During Partition, the city was the site of gruesome communal violence, and we also have narratives about leaders like Nehru jumping into rioting crowds trying to stop the violence. But we don’t have reliable numbers. After 1950, we do.

Opinion | P B Mehta writes: The Delhi darkness — Our rulers want an India that thrives on cruelty, fear, division, violence

During the Nehru years, Delhi had several small riots, but given how resolutely the state fought what it called the “communal poison”, the sparks did not become fires. It is only in November 1966 and May 1974 that riots led to more than 5 deaths. Delhi’s largest Hindu-Muslim riots took place after the destruction of the Ayodhya mosque. We recorded 39 deaths in December 1992.

Delhi 2020 has already gone beyond Delhi 1992, even though the numbers are not yet final. Its scale is only exceeded by Delhi 1984, when horrific anti-Sikh violence rocked the city. Scholars are convinced that the anti-Sikh riots were pogroms, defined by social sciences as a special class of riots when the police, instead of acting neutrally to crush riots, looks on while mobs go on a rampage against minorities, or it explicitly aids such violent mobs.

This takes us to the larger political significance of Delhi 2020. A raging issue in the ongoing debate is whether Delhi 2020 is a pogrom, not simply a riot. To some, this is a merely academic debate, which will not alleviate the pain and suffering of the victims. There is considerable merit in this claim, but only if we only confine our analysis to the current victims. If we think of the future, the significance of how to categorise the riots will become transparent. In case Delhi 2020 is a pogrom and it reappears elsewhere, let us be clear that the future victims will be abjectly helpless. Those committed to a pluralistic India must be ready for an eventuality of the worst kind.

Opinion | P Chidambaram writes: Many suspect that BJP wants people to take to the streets and polarisation to be complete

After reading and watching about 50 reports, I am convinced that the first day of Delhi violence was not a pogrom. Rather, it met the classic description of a riot, defined by conflict scholarship as a violent clash between two groups or mobs, in this case one in favour of the Citizenship Amendment Act and another against. But the next two days began to look like a pogrom, as the police watched attacks on the Muslims and was either unable to intervene, or unwilling to do so, while some cops clearly abetted the violence. Luckily, before such behaviour turned into the gruesome horrors of Delhi 1984, the violence came to a halt.

Three elementary political points are worthy of note. First, outside Kashmir, Delhi is India’s most heavily policed city. Delhi is also extensively covered by the media, national and international, capturing every newsworthy slice of the unfolding reality. Delhi is not comparable to the villages of Muzaffarnagar where, in September 2013, rioters could overwhelm the meagre police presence. If such violence can happen in Delhi, it can easily take place elsewhere. Muslims in the BJP-ruled states are especially vulnerable. Leaving aside Delhi, India’s police is under state, not central, control. If the BJP states push the police against the Muslims, only the conscientious and brave police officers will resist. Can one imagine the cruelties and the suffering, especially in the distant outposts, away from the media gaze?

Second, the argument about police failure, raised in some quarters, is highly suspect. It implies that the cops were committed to neutrality as a functioning principle, and to maintenance of law and order as a professional imperative, but could not deliver, even though they tried. This is hardly an inference one can draw, if cops allowed the lower-level politicians of the ruling party to spew hateful provocations in their presence and also told the reporters they had no instructions to act, even as violence took control of the streets. Legally, no instructions from the government are necessary for the cops to stop killings. The police can intervene on its own.

Opinion | Tavleen Singh writes: Modi’s image as world statesman has taken battering since his second term began

Third, why would India’s top leadership allow riots in its great moment of diplomatic glory? The leader of the world’s most powerful nation was in the country to pay tribute to India, the pictures of Trump, his family and India’s leader were on the front pages, and it seemed as though India’s rising power was given an exuberant broadcast all over the world. Even Beijing was paying attention. Within the next 48 hours, Delhi’s riots ruled the front pages. Glory quickly metamorphosed into concern, even shame. Is this how a rising India deals with its citizens?

We witnessed what social scientists call the principal-agent problem in its ugliest form. When bigoted leaders are chosen to lead state governments, when terror-indicted foot soldiers are picked to run for Parliament, when ministers shouting in campaigns “goli maaro saalon ko… (shoot the traitors)” go unpunished, a recognisably clear incentive structure is created within the party. Those displaying larger communal bigotry, those publicly abusing political dissenters as seditious traitors, think that they will be rewarded by the party. The tap can be turned off by the bosses, as happened after three days last week, but the agents below can also turn on the tap without any explicit instructions from the principals above.

Violence is thus built into a project that legitimates bigotry and equates dissent with national disloyalty. India’s rulers want to overturn the constitutional order. Regime partisans are already calling it a “civilisational war” — to hell with the Constitution, they imply. India’s citizenry is well and truly into a battle for constitutional values, which must be fought, most of all, with non-violent determination and vigour.

This article first appeared in the March 2, 2020 print edition under the title ‘Delhi and after’. The writer is director, Center for Contemporary South Asia, Sol Goldman Professor of International Studies and Social Sciences, professor of political science, Watson Institute for International and Public Affairs, Brown University

Opinion | Meghnad Desai writes: Why Delhi CM should be in charge of police