Poet Akhil Katyal Gajendra Yadav.

Poet Akhil Katyal Gajendra Yadav.

Akhil Katyal suggests a walk in Lodhi Gardens when I ask to meet. Later, straining to hear each other over the cacophony of a kitty-party afternoon in a south Delhi cafe, one gets an inkling why. Like his poems collected in Like Blood on the Bitten Tongue: Delhi Poems (Context, Rs 499) , Katyal, 34, is a poet and activist most at home amid the chaotic rhythms of the city’s streets and public spaces. There — in the crush of bodies in the after-office Metro rush, in the touristy bubble of Humayun’s Tomb or the steely resistance of Jawaharlal Nehru University — Katyal captures the city’s many faces: “Aditya from Khanpur who was 19 sped/ his auto so breakneck I bet I’d be dead/ so I thought I’ll talk, that’ll slow him/ ‘Kab se chala rahein hain?’ to bore him/ ‘Aaj hi learner’s mila hai!’ he said. (Limerick for the Danger Boy)”; or, “You can chew the sun here and spit it out/You can make the mighty eat dust/ It’s a university that we’re talking about/ Not a king’s court where we must. (For JNU)”.

Cities have built him — first Lucknow, with its Ganga-Jamuni tehzeeb, where he grew up in a Punjabi family, and where his missionary school insisted on the use of the Queen’s English over all others, and then the cosmopolitanism of Delhi, where he had come for graduate studies. “In Lucknow, you were pretty much confined to your family and the city they opened for you, and the school had its own universe. You get to know a city, including your own, only after you leave home. Of course, depending on your gender and your caste, the city opens to you in different parameters, but the fact that a city can stretch, that you can get lost in it, that you can move about in very incipient ways was a revelation. Delhi fascinated me, it still does. Later, I read Ismat Chughtai’s autobiography, in which she spoke of chahalkadmi — rambling aimlessly through the city, mulling over ideas — and somehow, it just made a whole lot of sense,” says Katyal, who is an assistant professor at Ambedkar University’s School of Culture and Creative Expressions.

Like Blood on the Bitten Tongue — a hat tip to one of his favourite poets, Agha Shahid Ali — follows Katyal’s How Many Countries Does the Indus Cross (2019). Like a city of many parts, it is tender and hopeful, defiant and dramatic, and wears its politics on its sleeves. From Delhi’s landmarks to its many languages, from queer love to friendships to his disdain for the ruling right-wing party, Katyal’s bilingual poems — flitting easily between Devanagari and English and set to Vishwajyoti Ghosh’s artwork — reference a world that is determinedly situated in contemporary socio-politics but with an intimacy that is born of his life of assimilation.

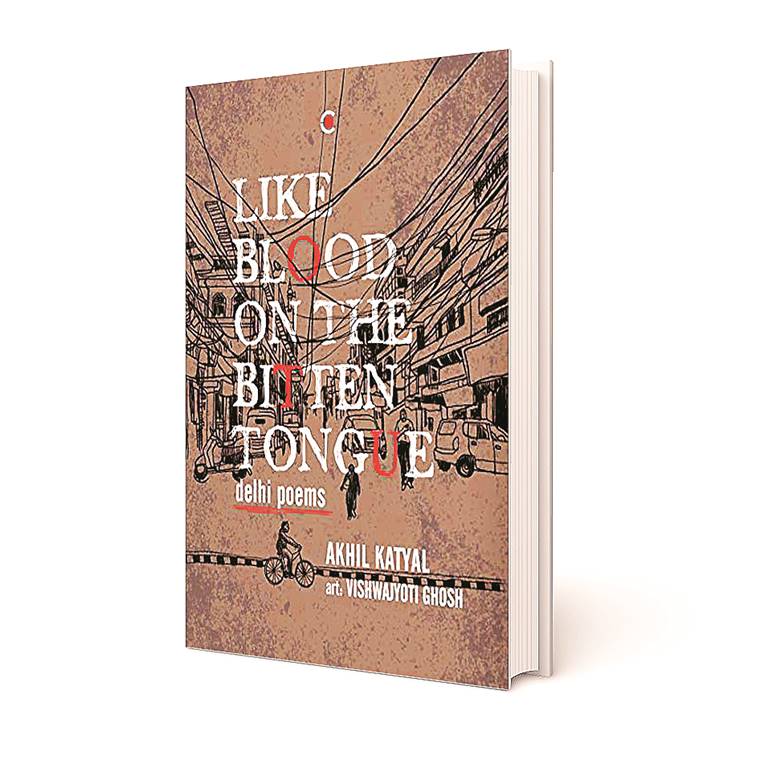

Cover of Like Blood on The Bitten Tongue: Delhi Poems

Cover of Like Blood on The Bitten Tongue: Delhi Poems

Over the last couple of years, Katyal, along with a bunch of contemporaries, that now include vernacular poets such as Hussain Haidry and Aamir Aziz, have responded to the ruptures in India’s community life with poetry on social media. Poetry has come to become one of the mainstays of dissent in the protests against the Citizenship (Amendment) Act and the proposed National Register of Citizens and against the crackdowns on students in universities. Dark times demand creative responses, says Katyal, and what can be more anarchic than poetry? “I was on duty during the Delhi assembly elections and one of the things I realised over the course of it was that this kind of core, ideological belief, driven by certainty, hatred and prejudice, is not as overwhelming as I’d imagined. There are lots of people who can be made to think with other vocabularies,” he says.

When he’d first landed up in Delhi, Katyal’s world had opened up in other ways, too. The university space taught him to debate and dissent, but also to listen in and to empathise. He’d known of his queer identity in Lucknow but it would be in university that he’d come out. “In class, we were discussing the imagery of (Christina Rosetti’s) The Goblin Market (often considered to be indicative of Rossetti’s feminist and non-heteronormative sexual politics) and I thought to myself, ‘Wait a minute, if we are talking about this, surely it’s okay to talk about how I feel.’ I had fabulous teachers who made it seem like it was not a big deal. The first person I came out to was my classmate, then my teacher, and, then, at the Rhodes interview,” he says, with a chuckle, before adding, softly, “Which is why, when university spaces are attacked, when students are told to just study and not concern themselves with the world, it feels strange. There’s a beautiful thing that Mukul Manglik, our history teacher at Ramjas College, used to say: ‘Where does the word university come from? From the universe, which means, surely, everything under the sun can be discussed here.’” He carries that universe in his poetry now, and in the novel that he hopes to write one day.