Atiku, 51, spoke about using his body as sculpture and healing through art.

Atiku, 51, spoke about using his body as sculpture and healing through art.

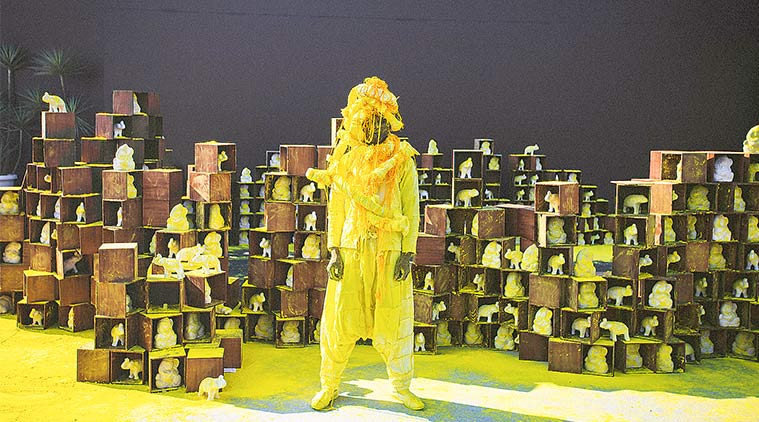

One of Nigeria’s pioneering performance artistes, Jelili Atiku is known to address sociopolitical and human-rights issues through his work. Conferred with the 2015 Prince Claus award, for his attempt to “…open up dialogue and influence popular attitudes”, he has performed at various prestigious platforms, including the 2017 Venice Biennale and the 2018 Manifesta. At his maiden performance in India at the India Art Fair last month, he emphasised on the need to embrace differences through his work Nobody is Born Wise. Atiku, 51, spoke about using his body as sculpture and healing through art. Excerpts:

Could you tell us about Nobody is Born Wise, for which you smeared turmeric on more than 100 Ganeshas and elephants?

I work with objects ontologically and try to incorporate their essence in my work. Ganesha is sacred and, through the performance, I was attempting to explore the inner connection people feel with religion. When I was invited to perform at the fair, my first thought was how could I respond to the national discourse. I was interested in the discussions on the CAA (Citizenship Amendment Act). I feel it is related to colonialism, and the manner in which the country was divided into separate entities. Postcolonialism comes with a lot of complex issues, just like the characteristics of Ganesha. The elephant figures represent how the animal moves in huge groups; similarly the diverse population of India should also stand united. Nigeria, too, has more than 200 ethnic groups. We should embrace our diversity and find strength in it.

The audience were an important part of the performance. You invited them to join you, just like you have in several of your earlier performances.

I don’t perform for the camera. The audience are an element in my work, they are participants. I want to get them to think about the issues. Each individual has her own distinct energy and when they come together, it leads to collective consciousness. In some of my preliminary sketches, I imagine where my audience will be. It is similar to the traditional performances in Yoruba, where the audience is indispensable.

Last month, during the performance of The Night Has Ears in Gropius Bau museum in Berlin, you did a healing ritual in the streets where the Holocaust took place.

I was looking at the history of the museum building and its neighbourhood, which is deeply connected to Nazism. We need to yield back memories of those days because the instances that are happening now are quite similar to what was happening back then — white supremacy in the US, pervading fascist ideologies, or even Brexit. We need to heal some of those memories and that is what I intended.

At his maiden performance in India at the India Art Fair last month, he emphasised on the need to embrace differences through his work Nobody is Born Wise.

At his maiden performance in India at the India Art Fair last month, he emphasised on the need to embrace differences through his work Nobody is Born Wise.

In 2016, you were charged with felony and arrested in Lagos for your performance Aragamago Will Rid This Land of Terrorism, that angered the king. You were released after six days at the intervention of the international human rights community. What had happened?

In 2014, three women were sodomised publicly in the market place in Ejigbo, Lagos. During the brutal assault, a concoction of wine and chilli pepper was poured into their private parts. Several people did not know about the incident for a year, after which people began to appeal to the king to respond to this act of abomination. I tried to book an appointment with the king, but he refused. So I conceived a performance to address the issue. The piece referenced Aragamago (the myth where energy is conferred onto the wife of Orunmila, the Yoruba God of wisdom) and the enormous power that women have to save the whole world. The king complained that we entered the palace and tried to destroy things, whereas we were on the streets. We were thrown in the prison and members of Oodua People’s Congress (OPC) destroyed my studio and terrorised members of my family. It was terrible. I had to go through six months of trial in court before I was cleared of all charges.

You trained as a sculptor but chose to pursue performance art, projecting your body as a sculpture. At times, self-harm becomes a part of your performance, like in 2017, when you poured used oil on yourself during Come Let Me Clutch Thee.

I was trained as a sculptor, but while competing my master’s studies I felt the need to use my body as a medium. My own body becomes a live sculpture. The performance is an intimate dialogue between me and the audience. There is an organic fluidity in the conversation. Performance art is among the most ancient practices in Yoruba. During the egungun (Yoruba masquerades), the artist creates colourful costumes, incorporates poetry, dance, culture, and for me that is a complete art form. At times, it becomes important to use my body to make the audience feel pain. Thousands of people live in poverty and die due to the effects of oil spillage and clashes over land. So when oil was discovered in the Cape province in South Africa, I was concerned. In preparing for the performance, I asked the organisers to get some used car oil that I could use. They said that it was dangerous to the body, but I wanted the audience to feel the pain I underwent. They must be able to experience real emotions. I poured the oil directly onto my body. Later, I had to undergo treatment for the exposure.

How would you describe the state of art and culture in Nigeria?

We are a nation with a strong historical, artistic culture but today no one values that. Most of our leaders still have colonial mentality. For the British, our culture and history were not a priority, it is the same with our present leadership. We don’t feel connected to our past. The entire Artists’ Village in Lagos was destroyed in 2016, no one protested because people don’t even know the value of those works.