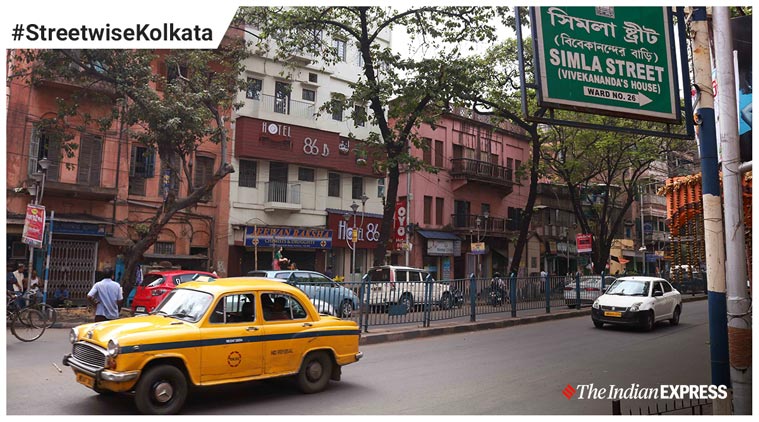

According to historical records, these trees may be considered the city’s oldest inhabitants and may have also lent their name to Simla Road, one of the oldest streets in Kolkata. (Express photo/Shashi Ghosh)

According to historical records, these trees may be considered the city’s oldest inhabitants and may have also lent their name to Simla Road, one of the oldest streets in Kolkata. (Express photo/Shashi Ghosh)

Every year during spring, patches of red blooms colour Kolkata’s cityscape, in stark contrast to the lifeless modern construction that has besieged the city during the last two decades. The deciduous trees on which these large, bell-shaped flowers grow, Bombax ceiba, are called simul in Bengali and are found across South Asia and parts of Southeast Asia.

Although now severely depleted in number, these simul trees once grew in abundance in the city. According to historical records, these trees may be considered the city’s oldest inhabitants and may have also lent their name to Simla Road, one of the oldest streets in Kolkata.

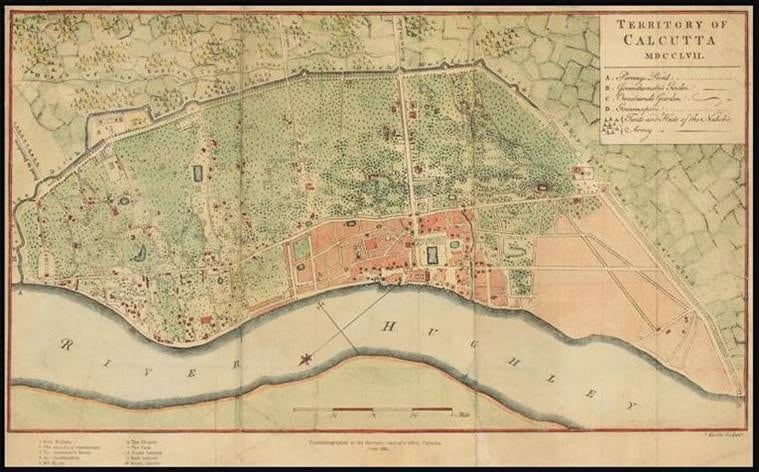

The neighbourhood of Simla Road lies close to Tangra, Topsia and Ultadanga, and was once a part of Dihi Panchannagram, a group of 55 villages that lay outside the Maratha Ditch, an approximately 5 kilometer ditch that had been excavated in 1742 to form a perimeter around the city of Calcutta to protect the British from an invasion by the Marathas that did not occur.

This rare photo-lithographic reproduction print of Thomas Kitchin’s map of Calcutta, titled ‘Territory of Calcutta MDCCLVII’, first issued in 1763, is one of the few mapped records of the Maratha Ditch, spelled ‘Morratoe Ditch’. (Source: Antique Maps Inc)

This rare photo-lithographic reproduction print of Thomas Kitchin’s map of Calcutta, titled ‘Territory of Calcutta MDCCLVII’, first issued in 1763, is one of the few mapped records of the Maratha Ditch, spelled ‘Morratoe Ditch’. (Source: Antique Maps Inc)

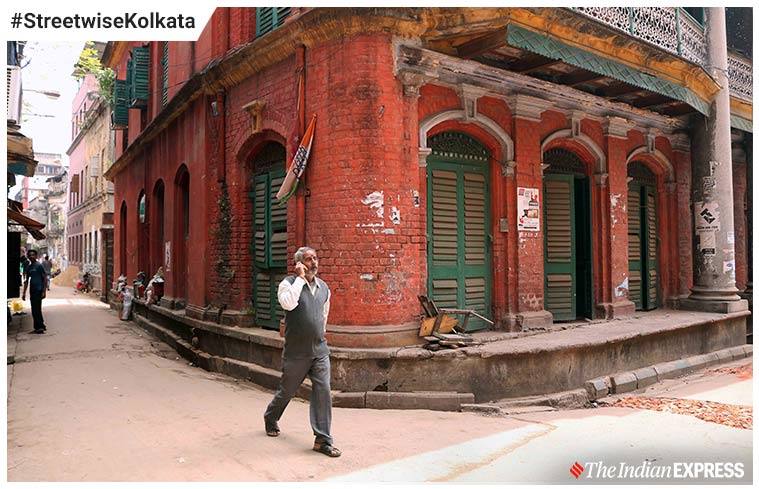

These villages that formed Dihi Panchannagram in 1758, fell outside the Maratha Ditch and marked the outer fringes of the city of Calcutta till 1893, when the ditch, having been a futile enterprise, was filled by the British. Writings by employees of the British East India Company indicate that the neighbourhood of Simla Road in its earliest days was sparsely populated, with largely forestland that had not yet been cleared for widespread habitation.

One of the earliest mentions of the neighbourhood can be traced, according to historian P. Thankappan Nair, to the December 1889 issue of the National Magazine, where Bengali scholar Sarat Chandra Mitra wrote: “The name Simla is derived from a great number of simul or silk-cotton trees (Bombax ceiba) which grew thereabouts and the place was therefore called Simulia. Simla is mentioned as existing so far back as 1742 though its site was occupied by jungles abounding with silk-cotton trees and stagnant ponds.” That the neighbourhood was uninhabited even during 1826 can be derived from Mitra’s writings where he indicates that “no native for the love of money could be got to go this way after sunset.”

“The name Simla is derived from a great number of simul or silk-cotton trees (Bombax ceiba) which grew thereabouts and the place was therefore called Simulia.” (Express photo/Shashi Ghosh)

“The name Simla is derived from a great number of simul or silk-cotton trees (Bombax ceiba) which grew thereabouts and the place was therefore called Simulia.” (Express photo/Shashi Ghosh)

English barrister and historian H.E.A Cotton, who lived and wrote extensively about Calcutta in his book ‘Calcutta, Old and New’ published in 1907, affirms that the “simul or cotton-trees gives its name to Simla.”

An interesting account of how the neighbourhood of Simla came to urbanised for settlement can be found in the book ‘Selections from Unpublished Records of Government for the Years 1748 to 1767 Inclusive Relating Mainly To The Social Condition Of Bengal, Vol.1’ by the Rev. J. Long. In a detailed entry for December 8, 1754, titled ‘Similia in Calcutta rented to Government’—‘Similia’ perhaps being a mispronunciation of the word ‘Simla’—it is stated in a despatch to court: “On the 8th August Mr. Holwell in a letter to the Board informed us he had been at some pains to prevail upon the Proprietors of a spot of ground called Similia to rent it to your Honors for the sum of Rs. 2,281 which he required our permission to take on your account as the situation (being part of Calcutta in a manner itself) had many advantages and its revenues yielded in its present management more than the sum we should pay, and he did not doubt would produce considerably more when in our hands. We have accordingly given him leave to take possession.” This entry goes on to indicate that it was a complicated matter and the Company officials experienced difficulties in completing acquisition of the land due to contesting claims by zamindars concerning it.

Writings by employees of the British East India Company indicate that the neighbourhood of Simla Road in its earliest days was sparsely populated, with largely forestland that had not yet been cleared for widespread habitation. (Express photo/Shashi Ghosh)

Writings by employees of the British East India Company indicate that the neighbourhood of Simla Road in its earliest days was sparsely populated, with largely forestland that had not yet been cleared for widespread habitation. (Express photo/Shashi Ghosh)

Some explanation for why in 1754 the Company was attempting to acquire this land can be found in the book ‘Old Fort William in Bengal; Vol. II’, published in 1906, it is mentioned that John Holwell, a British East India Company employee who served as a member of the Council of Fort William in Calcutta, wrote a letter to the Company that the district of Simla consisted of about 1,000 bighas of land and fell outside company jurisdiction.

In 1755, the Company succeeded in its quest and the Fort William Council wrote to the Company of Directors in December that year, explaining how Raja Kissenchand, Raja Krishna Chandra Roy of Nadia, had attempted to lay claim to Tengra (that later came to be known as Tangra) and parts of Simla. In the letter to the Company of Directors, the Fort William Council went into an elaborate explanation of how dramatically a local zamindar had assisted Company officials in forcefully dispossessing the servants of Raja Krishna Chandra Roy. The force with which the Company officials compelled Raja Krishna Chandra Roy left him no alternative but to agree to their demands. “We have heard no more of it from Raja Kissenchand with whom we live at present in a very good understanding,” says the entry by the Fort William Council.

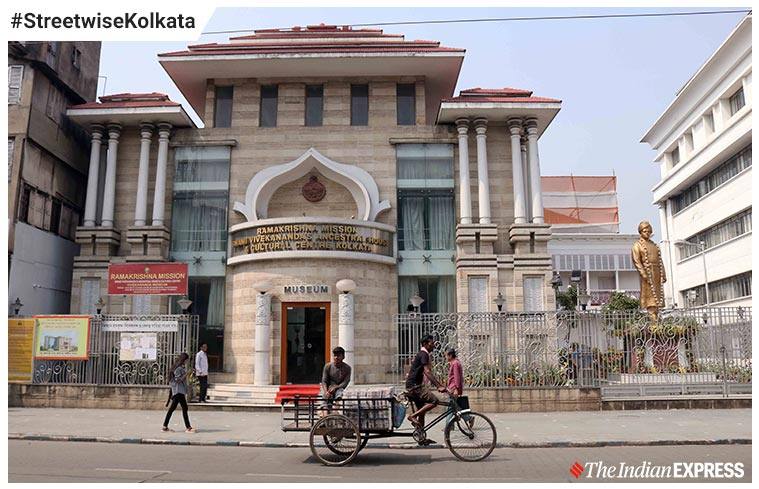

The most well-known residents of the neighbourhood of Simla however, was undoubtedly Swami Vivekananda, whose ancestral home still stands on the corner of Simla Road. (Express photo/Shashi Ghosh)

The most well-known residents of the neighbourhood of Simla however, was undoubtedly Swami Vivekananda, whose ancestral home still stands on the corner of Simla Road. (Express photo/Shashi Ghosh)

That was how the British came to fully acquire and incorporate the land of Simla into the city of Calcutta. Simla Road finds mention in some of the oldest maps of the city of Calcutta, including Wood’s map of 1784 and Upjohn’s map of 1794. Once the British took over the neighbourhood of Simla, the area began developing in earnest.

The most well-known residents of the neighbourhood of Simla however, was undoubtedly Swami Vivekananda, whose ancestral home still stands on the corner of Simla Road. According to the Ramakrishna Mission that manages the property today, the house that Swami Vivekananda once lived in had been overtaken by tenants and other individuals renting rooms for commercial enterprises and had remained in a dilapidated condition for years. The legal tussle between the Ramakrishna Mission and tenants who refused to vacate the property went on for years till in the early 2000s, the matter was resolved by the courts in Kolkata that the West Bengal government would acquire the property from the tenants in cohesion with the Ramakrishna Mission.

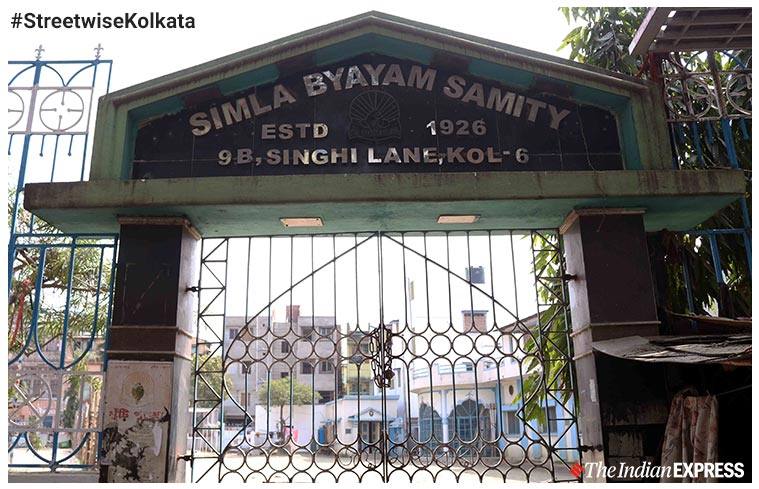

A five-minute walk from Swami Vivekananda’s house is the 94 year-old Simla Byayam Samiti, a local fitness club started by Atindra Nath Bosu, a freedom fighter who lived in the neighbourhood. (Express photo/Shashi Ghosh)

A five-minute walk from Swami Vivekananda’s house is the 94 year-old Simla Byayam Samiti, a local fitness club started by Atindra Nath Bosu, a freedom fighter who lived in the neighbourhood. (Express photo/Shashi Ghosh)

The property has been restored over the years and has been converted into a research and cultural centre and museum. A handful of old houses remain in the neighbourhood although much is changing, like elsewhere in the city. A five-minute walk from Swami Vivekananda’s house is the 94 year-old Simla Byayam Samiti, a local fitness club started by Atindra Nath Bosu, a freedom fighter who lived in the neighbourhood.

According to Somnath Dutta, a manager of the Simla Byayam Samiti today, the fitness club was started by Bosu as a gymkhana to provide physical fitness training for freedom fighters in their war against British rule. Not only were young men given training in sports, but they were also provided training in basic weapons and defence, much like other underground gymkhanas that operated during that time. Dutta says club records show that leaders in India’s freedom movement, like Subhash Chandra Bose and Bidhan Chandra Ray, regularly visited the gymkhana.

According to Somnath Dutta, a manager of the Simla Byayam Samiti today, the fitness club was started by Bosu as a gymkhana to provide physical fitness training for freedom fighters in their war against British rule. (Express photo/Shashi Ghosh)

According to Somnath Dutta, a manager of the Simla Byayam Samiti today, the fitness club was started by Bosu as a gymkhana to provide physical fitness training for freedom fighters in their war against British rule. (Express photo/Shashi Ghosh)

The Simla Byayam Samiti is not only unique for its contributions during India’s freedom struggle. It also gave Bengal the first ‘Sarbojanin’ Durga Puja; the term ‘Sarbojanin’ meaning ‘for everyone’. Prior to the start of the concept of Sarbojanin Durga Puja, the autumn festival would be held in private spaces within homes or in the rajbaris of rich zamindars who usually sent out invites only to family and friends. This new form of celebrating the festival allowed common people to gather in public spaces to celebrate the biggest and most important festival in Bengal, in forms that are still widely prevalent in the state and elsewhere in the world where the festival is celebrated.

Simla Street’s contributions to Calcutta’s history and culture don’t end there. A local street food and favourite that possibly only the most devoted epicurean can know about, is the fish kochuri, a food so well loved that Bengali restauranter Anjan Chatterjee ensured that it found mention in his Oh! Calcutta Cookbook.

The trees in the neighbourhood of Simla Street are fewer these days and old houses are holding on for as long as they can. In the season of spring in Kolkata, if one looks up while walking down Simla Street, blooms of red simul burst into view, sometimes falling onto the pavements below, coating the ground with their disintegrating florets. Not many know that these trees are some of the oldest inhabitants of Simla Street.