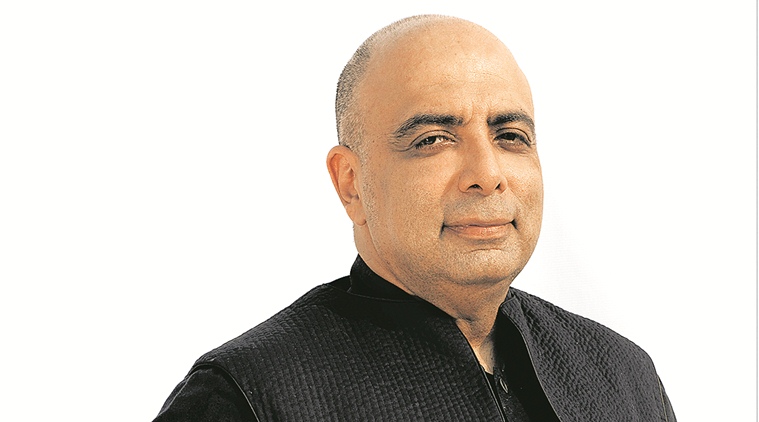

Fashion designer Tarun Tahiliani

Fashion designer Tarun Tahiliani

Chances are you hear Tarun Tahiliani before you actually see him. The contagious energy and voice of one of India’s foremost couturier’s will reach you before his looming six-foot presence does. As he moves through the room, greeting people, adjusting the drape on a mannequin, picking up a stray coffee cup and climbing up a platform to make a speech, Tahiliani’s infectious presence fills his Gurugram workshop atrium. It was a day-long event to celebrate 25 years of TT’s (as he is fondly called) formal entry into the world of fashion. Nearly 25 of his most iconic looks on mannequins showed his journey, how he took the traditional lehenga and turned it around with a flamboyant corset or a tang-pajama from the Mughal era, which he paired with a sheer golden cape. An emerald-gold duster jacket with cigarette-pants, is a favourite, which he says “one can wear to a wedding”, as he takes us on a tour.

“In India, fashion is still largely a mom-pop operation, where we don’t introspect or archive in a formal, organised fashion,” says Tahiliani, 57. Born and brought up in Mumbai, in a Sindhi family, armed with a Wharton degree, he began with the family business of oil-field equipments. Fashion happened in a serendipitous way, in which his wife, Sailaja (Sal) had a role to play. “We had just came back from the US, and we were broke. We lived near the Taj Hotel in Mumbai, and knew Pierre Cardin was doing a show. Sal, who went to be a usherer, was asked if she would audition as a model since she’s tall. And here I was watching all this and thinking this is a world I could be a part of,” says Tahiliani. He started the first multi-designer boutique of India, Ensemble in Mumbai in 1987, with his sister Tina and his wife. His eponymous label was later launched in 1995, with a stint at Fashion Institute of Technology New York, in between.

Drape and silhouettes always fascinated Tahiliani, and Indian embroidery held a special place in his heart. “Embroidery is something that the West can’t teach us. We have learnt it from our masterjis. India has a rich draping tradition, not a tailoring one. We drape our saris, our lungis, our pagdis. And the drape is a signature; a navvar from Saurashtra is different from the Konkan,” he says. “It took us 20 years to get a dhoti saree,” says Tahiliani. “But back then, there were no good tailors, they didn’t know what arm holes were. Now we have taken traditional handloom and paired it with fit and construction. We need to have solutions — the naada with a churidaar doesn’t work, that’s how they got zippers. Designers need to give solutions,” he says.

Tahiliani’s designs have always been about making the traditional, functional. “The idea of a bride wearing a 20 kg lehenga, in this hot, tropical country, and then walking and dancing in it. I couldn’t watch it,” he says. He got a bride to wear a cape with her lehenga, and even a veil, or a cloak-like blouse, held together by a fastening on the chest.

“A Tarun Tahiliani bride is a rebel at heart, just like him. I remember every sixth design would be an eclectic, crazy one, maybe not wearable by a chunk of brides,” says designer Amit Aggarwal, who was apprentice under Tahiliani for three years in early 2000s. “He has a distinct habit, perhaps something even he doesn’t register. We called it the ‘cheek test’. To approve a fabric, TT would feel it against his cheek, unlike the rest of us who would feel it with our fingers. His keen attention to detail, and his wicked sense of humour is what I always remember,” says Aggarwal.

Amidst all the celebrations, Tahiliani has made time to attend the various protests in the Capital, from those in Jamia Millia Islamia to Jawahar Lal Nehru University. While the Indian fashion fraternity has largely been aloof from the larger concerns of the world around them, Tahiliani comes as a welcome break. “A lot of people who work with me are Muslims, and a great part of our craft and embroidery traditions have Islamic roots. I think we are chipping away at our own social fibre. We have always been such a secular country, that’s what has made us what we are,” he says.