Porsche isn’t alone. Across the motor industry, companies large and small are using the same techniques to produce everything from prototypes or pattern parts for moulds to one-off, functioning components. They fall under the grand name of reverse engineering because they involve deconstructing a finished component to determine how to remanufacture it.

One company doing this work is A2P2, based in Nottingham. It’s at the back of a busy workshop that’s home to INRacing, a company specialising in the restoration, maintenance and sale of historic road and race cars and founded by a chap called Ian Nuthall.

When I visit, the workshop is filled with rare motors, including a 1959 Tec-Mec Maserati, a 1959 Lotus 15 once raced by Graham Hill, a couple of 1952 Cooper Bristols and a 1965 Autodelta Alfa Romeo GTA. A2P2 has had a hand in helping to keep them active, as I discover when I meet its founder, Alistair Pugh.

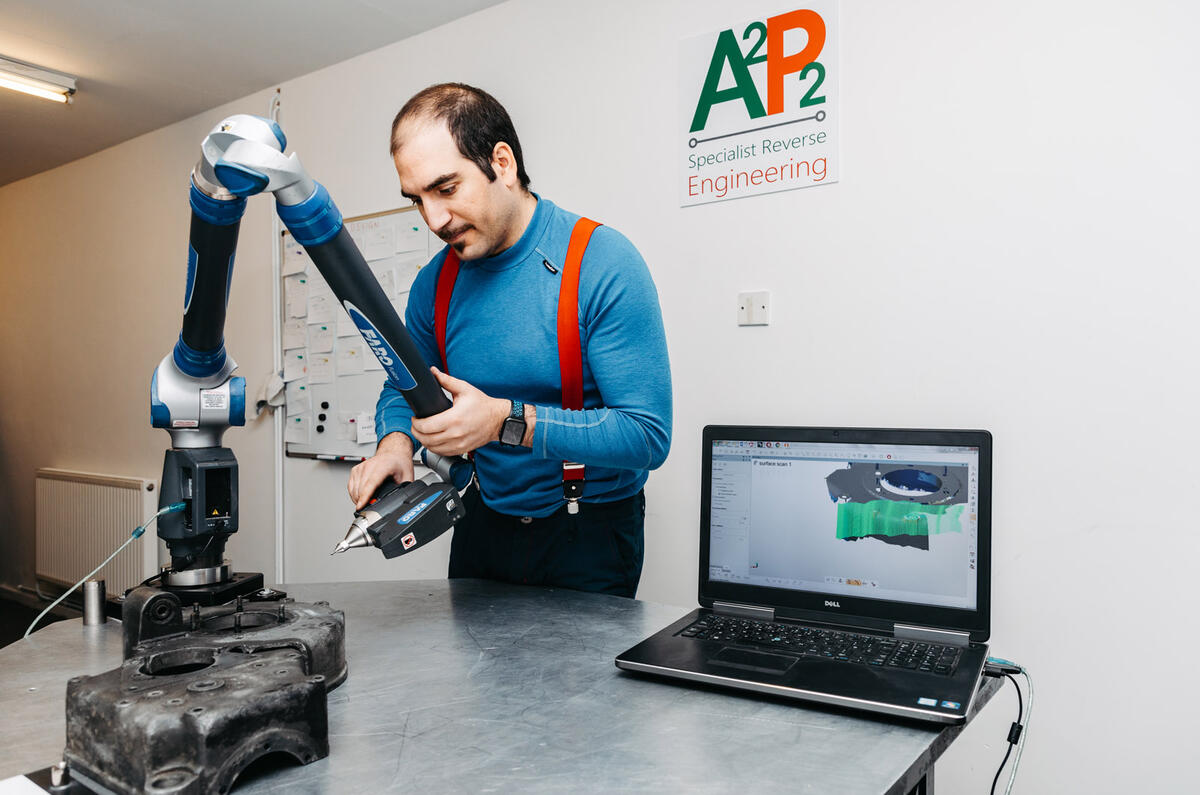

In contrast to INR’s workshop with its ramps, lathes and even a huge five-axis CNC milling machine, Pugh’s place is a high-tech oasis of calm. In one corner is a 3D printer, methodically layering up, in plastic, a bevel box for a pre-war, chain-driven Frazer Nash. Once completed, it will form the pattern for a sand cast moulding in metal. As it quietly goes about its business, Pugh draws my attention to the room’s other occupant: a 3D laser scanner. Looking like an angle-poise lamp but with a probe at the end rather than a bulb, it’s fixed to a sturdy metal table and connected to a laptop.

Pugh’s colleague, Alberto, shows how, by painstakingly moving the probe around a component – in this case, the diff casing from a 1952 Alta GP car – he can capture and digitise its every dimension, including the internal faces of the screw bores. The result is an accurate digital representation that can be converted into a CAD file for a 3D printer or into an engineering drawing for a machine shop to follow.

“‘From gaskets to gearboxes: scan it, draw it, make it’, we like to say,” explains Pugh. “Laser scanning and 3D printing have so many uses, from enabling classic car owners to have a digitised record of their car from which body panels, for example, can be recreated after a crash, to producing replica parts in plastic as a pattern for a sand cast or simply to test fit and function.”

On that point, he takes the other half of the Alta’s diff casing, produced earlier in plastic by the 3D printer, and inside it places the original crown wheel and pinion, and limited-slip differential so I can see how they fit snugly into their respective places.

But should it all look like just moving a probe and clicking a mouse, Pugh is quick to point out that interpreting the data and knowing what is possible from a manufacturing perspective are crucial. The former graduate engineer speaks from experience, having started out spannering for Nuthall before moving into contract work with Ford, Aston Martin and Jaguar. In fact, it was Nuthall who lent Pugh the £125,000 necessary to buy his first scanner.

Join the debate

Cersai Lannister

An answer!

I have been fretting about replacing components on my 959, which the writer helpfully tells us is a rare car. Now, we have an answer, 3D printing. But maybe someone can answer me three questions not considered in the article:

Add your comment