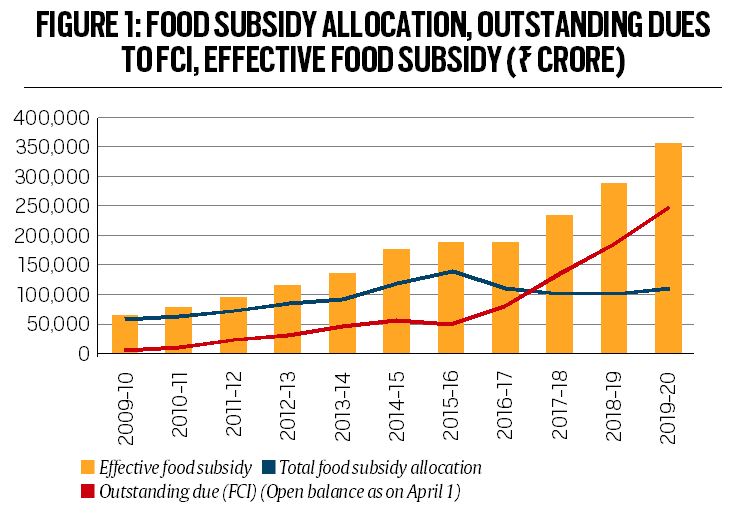

If there is one thing that bewilders a reader of the Union budget for 2020-21 in the agri-food space, it is the massive reduction in food subsidy. The revised estimates (RE) for food subsidy for 2019-20 have been slashed by a whopping Rs 75,552 crore — from the budgeted estimate (BE) of Rs 1,84,220 crore to Rs 1,08,668 crore (RE). For the next fiscal year, the budget estimate has been kept at Rs 1,15,570 crore. One wonders whether any major reforms have been undertaken in the grain management system or in the National Food Security Act such that this massive reduction in budget estimates is feasible. Alas, it’s only a sleight of hand by our financial experts at the ministry of finance. The Food Corporation of India (FCI) has been asked to borrow more from a myriad sources, but most importantly from the National Small Savings Fund (NSSF). An item that should have been in the budget, is now getting reflected as outstanding dues of FCI.

If there is one thing that bewilders a reader of the Union budget for 2020-21 in the agri-food space, it is the massive reduction in food subsidy. The revised estimates (RE) for food subsidy for 2019-20 have been slashed by a whopping Rs 75,552 crore — from the budgeted estimate (BE) of Rs 1,84,220 crore to Rs 1,08,668 crore (RE). For the next fiscal year, the budget estimate has been kept at Rs 1,15,570 crore. One wonders whether any major reforms have been undertaken in the grain management system or in the National Food Security Act such that this massive reduction in budget estimates is feasible. Alas, it’s only a sleight of hand by our financial experts at the ministry of finance. The Food Corporation of India (FCI) has been asked to borrow more from a myriad sources, but most importantly from the National Small Savings Fund (NSSF). An item that should have been in the budget, is now getting reflected as outstanding dues of FCI.

Figure 1 gives the implications of this. In order to gauge how much is the effective food subsidy in the country, the budget numbers are becoming totally irrelevant. One needs to add the actual subsidy numbers reflected in the budget to the outstanding dues of FCI. If one does that, the effective food subsidy turns out to be Rs 3,57,688 crore. By not provisioning for it fully in the budget, and not undertaking any reforms in the foodgrain management system or the NFSA, the government is only postponing the crisis.

While the Economic Survey clearly states that the coverage under NFSA needs to be revisited, and brought down to say 20 per cent of population, the budget did not bite this bullet. Maybe something will come up later in the year. In the meantime, it is worth noting that the expected cost of rice to FCI in 2020-21 is going to be about Rs 37/kg, and for wheat it will be Rs 27/kg. The issue price, that covers 67 per cent of the population, is just Rs 3/kg and Rs 2/kg respectively. Can 67 per cent of the Indian population not afford even basic food? If so, what is the development that we have been talking about all these decades?

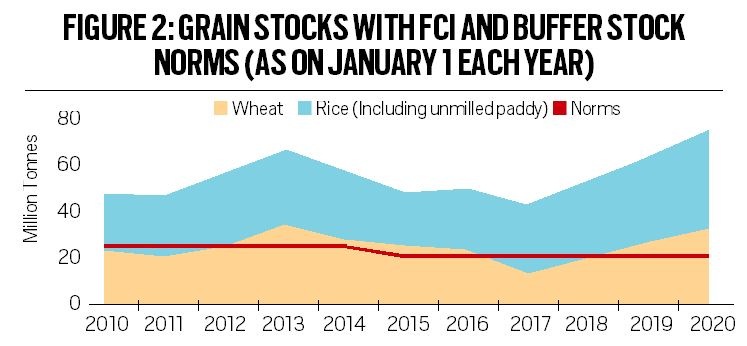

Now, look at the grain situation in the country. Compared to a buffer stock norm of 21.4 million tonnes, actual stocks with FCI (including unmilled paddy) were 3.5 times higher. It speaks of a colossal waste of scarce resources, especially when tax revenues have been sluggish.

Given that Skymet has predicted that the coming wheat crop is going to be one of the best in many years — it is likely to touch 113 million tonnes — and with procurement prices being above global prices, the chances of wheat exports are bleak unless there is a subsidy for exports. And that will be challenged in the WTO. So, one should expect a piling up of grains stocks with a record procurement of wheat. FCI may run out of storage capacity. Stock levels may touch 85-90 million tonnes, or even more, by July 1, 2020.

This raises some fundamental questions. One, is the government ignorant of the impending crisis of plenty? Second, does it realise that the policy of procurement prices (50 per cent above cost A2+FL), without looking at the demand side, is likely to create more troubles for the government? Third, does the government have any plan to reform the public distribution system under NFSA?

The budget does not give any indication of reforms in the grain management system that may be ushered in in months to come. In their absence, one wonders what is the game plan of the government. Reforms in foodgrain management have to start with reforming the PDS system, and gradually moving away from grains to cash transfers. The policy of procurement prices, with open-ended procurement in the Punjab-Haryana belt is doing more damage by depleting the water table and not letting crop diversification take place. This is very unfortunate as the “dead loss” in grain management runs to more than Rs 1,00,000 crore. This does not speak good of the government. It looks like the government’s attitude is like an ostrich with its head in sand, nay grain.

Interestingly, when the Narendra Modi 1.0 government came in, a high powered committee was set up to reform the grain management system under the former Union food minister, Shanta Kumar. The report is on the website of FCI. What is needed is the courage to bite the bullet. The Economic Survey talked of moving in the direction of cash transfers, but the government seems to have developed cold feet. Public money is being wasted year after year, and that runs into thousands of crores. At a time when the government is scratching its head desperately to raise revenue, nothing can be more ironical that this.

The other part related to this is the fertiliser subsidy, which is largely used in wheat and rice. The budget estimates for 2020-21 show a reduction in the subsidy, while dues of the fertiliser industry keep on piling. The fertiliser industry estimates that by April 2020, the dues will be roughly Rs 60,000 crore. While FCI has been asked to borrow, the fertiliser industry does not have that type of window. It is feeling totally demoralised. No private player wants to come and invest in this sector. No wonder all new plants are being set up by the public sector, which will be another major problem in years to come. And this is happening when the budget speaks of zero budget natural farming. One wonders whether the left hand of the government realises what the right hand is doing.

Gulati is Infosys Chair Professor for Agriculture and Das is senior consultant at ICRIER