Nearly three-fourths (72%) of Jatavs, two-thirds of Balmikis and two-thirds of the other Dalit castes reposed their faith in the party yet again. (Express Photo: Prem Nath Pandey)

Nearly three-fourths (72%) of Jatavs, two-thirds of Balmikis and two-thirds of the other Dalit castes reposed their faith in the party yet again. (Express Photo: Prem Nath Pandey)

Written by Shreyas Sardesai

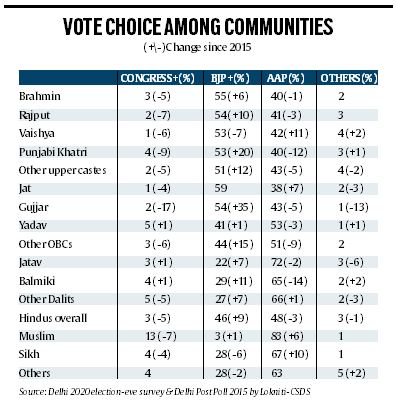

The AAP has emerged as Delhi’s catch-all party for the second successive election with the umbrella coalition of castes and communities. It has retained this characteristic from 2015, albeit with some minor dents made by the BJP in 2020. An analysis of the caste and community-wise voting patterns captured by Lokniti’s poll-eve survey shows that AAP has yet again swept the vote of the Dalit communities and religious minorities, who together account for one-third of the city’s total electorate.

Nearly three-fourths (72%) of Jatavs, two-thirds of Balmikis and two-thirds of the other Dalit castes reposed their faith in the party yet again. While these figures are impressive, there has been some erosion of Dalit support for AAP when compared with the 2015 elections, particularly among the Balmiki community.

The AAP’s strongest supporters for the second straight election have been voters belonging to the Muslim community, 83% of whom voted for it. This massive support for AAP among Muslims, who constitute 13% of Delhi’s population, is six points higher than the 2015 elections and comes amid protests against the Citizenship Amendment Act and talk of a possible National Register of Citizens.

This level of consolidation among Muslims in favour of AAP is perhaps the highest ever in Delhi, even greater than the support the Congress used to get among Muslims in elections held during Sheila Dikshit’s time. In fact, Muslim share in AAP’s overall vote is 20% this time, higher than even Dalits. In 2015, it had been 17%, two points lower than that of Dalits.

The AAP’s strongest supporters for the second straight election have been voters belonging to the Muslim community, 83% of whom voted for it.

The AAP’s strongest supporters for the second straight election have been voters belonging to the Muslim community, 83% of whom voted for it.Delhi’s other prominent religious minority, the Sikh community, 3-4% of its population, has also yet again rallied behind AAP, and in much higher proportions. Back in 2015, during the first AAP wave, 57% of Sikhs had voted for the party. This time around, the figure has gone up to 67%, the highest gains made by AAP in any community. The BJP, whose alliance with the Shiromani Akali Dal had run into trouble, saw its support among Sikhs decline by 6 points.

That being said, such an enormous vote share of AAP wouldn’t have been possible with just Dalit and minority support. The support received by the party from OBC and upper caste communities in the face of BJP’s Hindutva onslaught is equally significant. Among OBC communities, for instance, while the party lost some support among lower OBCs (roughly 12% of the electorate) to the BJP, among Gujjars and Yadavs (6% of the electorate), it more or less managed to retain its vote share.

The Gujjar vote, however, which had gone towards Congress and smaller parties in 2015, got completely polarised this time, with the BJP winning majority support among them. The gains for AAP as far as OBCs are concerned came among the Jats, 38% of who voted for the party as opposed to 31% last time. The BJP however retained its 2015 support among Jats, emerging as their most preferred party.

As far as upper castes are concerned, anywhere between 40-45% of Delhi’s electorate, the BJP made a comeback among them, winning majority of their support, but the AAP was not far behind. The collapse of the Congress saw the BJP gaining substantially among these communities, particularly the Punjabi Khatris, among whom its vote share increased by 20 percentage points.

The AAP, on the other hand, lost 12 points in support among Punjabis, who had been one of its biggest supporters in 2015. The BJP also made gains among both Brahmins and Rajputs, and these too seem to have come from the Congress’s kitty. The biggest setback for the BJP, however, came among the Vaishya community, which has been one of its strongest supporters in the past.

Even though the party secured 53% of their support, this was 7 points lower than the last assembly election. The BJP losses among Vaishyas directly benefited the AAP, which saw its vote share among the community, to which Arvind Kejriwal belongs, go up from 31% to 42%.

Overall, it could be argued that this election saw a polarisation of upper and middle caste groups in favour of BJP, and backward and minorities in favour of AAP — but the former was slightly weak compared to the strong polarisation of the latter.

(The author is associated with Lokniti-CSDS)