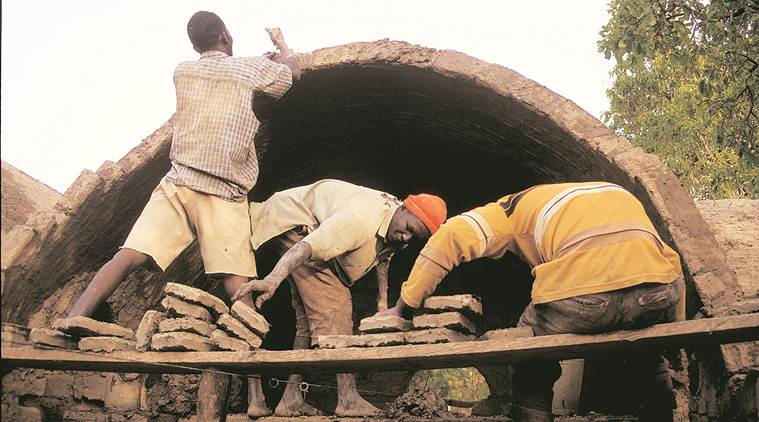

A Nubian vault home in Burkina Faso

A Nubian vault home in Burkina Faso

Had it not been for the announcement of the abrogation of Article 370, Delhi-based Peeyush Sekhsaria, an architect by training and photographer by choice, could have exhibited ‘A House for Mr Yabako’ in Ladakh last August. But Ladakh’s loss is the Capital’s gain. The 28 photographs — of grim ladies inside traditional vaulted houses, masons at work, gleeful men outside homes with Nubian vaults — are printed on handloom cloth (for easy travel, sourced from Andhra Pradesh weavers’ cooperatives), while little models made with upcycled shuttlecock boxes simulate the vault construction. The play of sun and shade in the images is reminiscent of his earlier works. And yet, the shots aren’t “stunning”, but each tells a story — they document the ordinariness of the ordinary at work.

The show is a throwback to his photographs from 2004-05, when, during his Master’s degree at CRAterre, France, Sekhsaria visited Mali to build schools for the Dogon ethnic groups in the Cliffs of Bandiagara, a Unesco World Heritage site. He recalled a meeting with members of the NGO La Voute Nubienne, who facilitate building Nubian vaults in Burkina Faso, just across the border from where he was. So, he slung his camera, hopped on to a second-hand vehicle with only windows for entry-exit, and had fermented non-alcoholic milk drink as “water supply” for four intense days of shooting. He travelled with the masons, site to site, to see how this technique was a success in a place where it seemed a little impossible.

Peeyush Sekhsaria

Peeyush Sekhsaria

Burkina Faso falls in the semi-arid Sahel region, south of the hot and dry Sahara desert, where stands Nubia (an ancient civilisation along the Nile; now in south Egypt and north Sudan), which birthed this construction method. The Nubian vaults (storerooms/granaries), built over 3,500 years ago at another Unesco World Heritage site, the Ramesseum temple in Luxor, Egypt, are still standing. The technique was revived in the ’40s by Egyptian architect Hassan Fathy, who built the New Gourna village to relocate an entire village from atop an archaeological site, from where people would otherwise steal artefacts and sell in the market.

Nubian vaults, which Sekhsaria, 45, calls “buildings in air”, look like any other vault but uses just mud, no formwork (the support frame/ structure) or timber (costly and unavailable). In India, he says, the Auroville Earth Institute has developed the Nubian technique to build other kinds of vaults (cloister and groined domes). It is a quick way to build structures with minimal maintenance. “Sure, it can be destroyed by heavy snow/ rains/ floods or earthquakes, but so does steel corrode and timber rots, and is eaten by termites,” says architect Sanjay Prakash, who opened the show.

Can Nubian vaults, suitable for extreme dry climates, resolve housing issues for the poor in certain parts of India? “It would be too generic to say that, no single technique can be a solution; there has to be a menu, and on that the Nubian vault definitely finds a place,” says Sekhsaria, who would be giving a talk on this subject, chaired by KT Ravindran, on Saturday at the IIC Annexe.

But, who is Mr Yabako? Yabako is an everyman, it is a common name in the Boromo region of Burkina Faso. “I use it in a very generic way, to demystify the construction style and see it as a home, to tell the human story: those building it, how they’re doing it, and who are living in it,” he says.

The exhibition is on display till February 18, 11am-7pm, at IIC Annexe