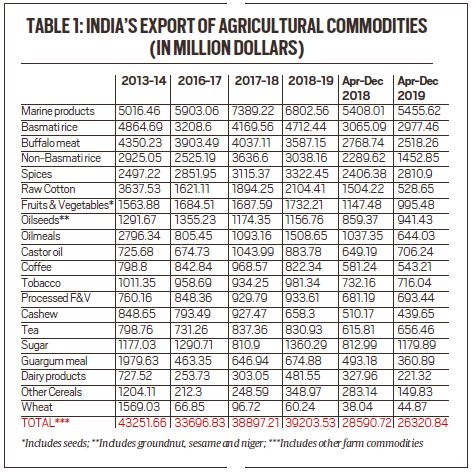

India’s agri exports peaked at $ 43.25 billion in 2013-14 and plunged to $ 33.70 billion by 2016-17.

India’s agri exports peaked at $ 43.25 billion in 2013-14 and plunged to $ 33.70 billion by 2016-17.

India’s agricultural trade surplus has narrowed in the current fiscal, with exports falling alongside rising imports.

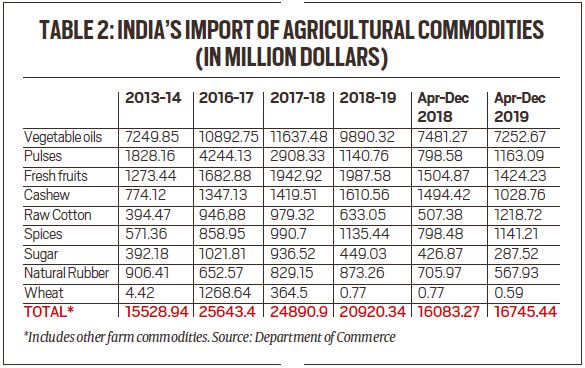

According to the latest Commerce Ministry data, total farm exports during April-December 2019, at $ 26.32 billion, stood 7.9% lower than the $ 28.59 billion for the first nine months of 2018-19. At the same time, imports went up 4.1% from $ 16.08 billion to $ 16.75 billion. As a result, the country’s agricultural trade surplus has reduced from $ 12.51 billion in April-December 2018 to $ 9.58 billion in April-December 2019.

India’s agri exports peaked at $ 43.25 billion in 2013-14 and plunged to $ 33.70 billion by 2016-17, following a crash in international commodity prices. The same period also witnessed a jump in imports from $ 15.53 billion to $ 25.64 billion and a corresponding shrinkage in the farm trade surplus from $ 27.72 billion to $ 8.05 billion. This trend was partly reversed thereafter. By 2018-19, exports had recovered to $ 39.20 billion and with imports, too, dropping to $ 20.92 billion, the surplus widened to $ 18.28 billion. But that revival has been reversed yet again in the first three quarters of 2019-20.

Table 1 shows that shipments of most agri-commodities from India have registered a decline during April-December 2019 relative to the previous year. The sharpest dip has taken place in cotton and rice, especially non-basmati grain. In cotton, the country has, for the first time since 2004-05, turned a net importer. Imports of the fibre, at $ 1.22 billion (table 2), exceeded exports of $ 528.65 million. This is a far cry from the all-time-high exports of $ 4.33 billion achieved in 2011-12, which plummeted to $ 1.62 billion by 2016-17 and edged up to $ 2.10 billion in 2018-19, before nose-diving afresh.

As far as rice goes, the best year for India was 2017-18, when it shipped out 128.75 lakh tonnes (lt). That included 88.18 lt of non-basmati (valued at $ 3.64 billion) and 40.57 lt of basmati ($ 4.17 billion, below the 2013-14 high of $ 4.86 billion).

However, this fiscal has seen a dip in both basmati and non-basmati exports. Basmati rice exports have taken a hit, particular to Iran due to payment problems arising from US sanctions. The uncertainty — Iran accounted for $ 1.56 billion out of India’s $ 4.71 billion basmati exports in 2018-19 — has worsened after the killing of the Islamic nation’s top military commander by a US airstrike early last month. Indian non-basmati rice goes mainly to African countries, which have, of late, found it cheaper to buy from China, Vietnam and Thailand. The situation should improve somewhat with the ongoing Coronavirus epidemic, which has revived demand for grain from India.

India, in 2011-12, emerged as the world’s No. 1 rice exporter and also came close to attaining that status in cotton (after the US). Further, in 2014, the country became the biggest bovine meat exporter. While India is still the largest shipper of rice, it has now been relegated to No. 3 position in cotton (behind the US and Brazil) as well as bovine meat

(after Brazil and Australia). Buffalo meat exports, which surged from a mere $ 341.43 million to $ 4.78 billion between 2003-04 and 2014-15, have since slipped to $ 3.59 billion in 2018-19 and continued their slide this fiscal. Even marine products, which had a good run and reached $ 7.39 billion in 2017-18, have lost momentum. Guar-gum and oil-meals are the other major exports that are today a pale shadow of their peaks of $ 3.92 billion and $ 3.04 billion, respectively achieved in 2012-13.

The only two agri-commodities to have posted significant growth in 2018-19 as well as the current fiscal are sugar and spices. Sugar exports in 2019-20 are on course to match their previous 2011-12 record of $ 1.84 billion — thanks largely to a government subsidy of up to Rs 10,448 per tonne (it was approximately Rs 11,500 in the 2018-19 season). In spices, India has, interestingly, emerged as both a big exporter as well as importer of spices. The top three contributors to the country’s spices exports in 2018-19 were chilli (valued at Rs 5,411.17 crore), mint products (Rs 3,749.33 crore) and cumin (Rs 2,884.80 crore). In contrast, its imports of so-called traditional plantation spices — pepper and cardamom — now exceed exports.

The increase in farm imports so far in 2019-20 has been driven primarily by pulses. Pulses imports soared from $ 1.83 billion in 2013-14 to $ 4.24 billion in 2016-17. With higher domestic production, in response to hikes in MSPs, the Modi government clamped quantitative restrictions, apart from raising tariffs, on imports. It led to pulses imports falling to $ 1.14 billion in 2018-19. A lower 2019 kharif crop has prompted the government to allow more imports, which is also reflected in the data for April-December. However, edible oil imports are set to decline for a second consecutive year, from the $ 11.64 billion level of 2017-18.