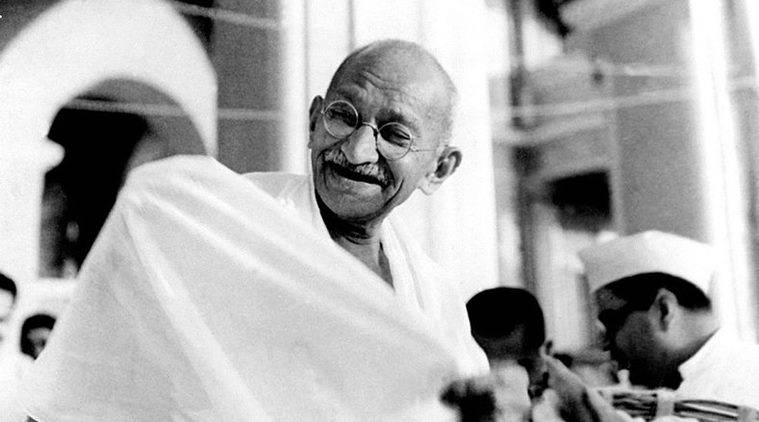

Mahatma Gandhi. (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

Mahatma Gandhi. (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

‘Mahatma Gandhi’s Clock’ is the title of a recent poem by the noted Hindi poet, Rajesh Joshi. The poem starts by telling Gandhi that his clock has stopped. The next few lines, in rough translation, are: “We are citizens of a period which has neither memories nor dreams/ The tidal waves raised by a fistful of salt/ have retreated/ Dead fish, snails and crabs litter the sand”. The despair is not difficult to explain.

Joshi lives in Bhopal. As a city, it received more generous state support than any other city for artistic and literary activities. Historically too, Bhopal had inherited a unique ethos of cultural confluence. None of this could help Bhopal survive the onslaught of polarising politics. In the latest parliamentary election, Bhopal’s choice of its representative was not affected by the candidate’s declared appreciation of Gandhi’s murder. Silence and fear descended on the city’s creative people. Joshi is among the few that have broken this silence through poetry. His despair is understandable, but his idea that Gandhi is no longer a living memory may not be true. Things happening in different parts of India suggest that Gandhi is enjoying an afterlife.

Throughout the 150th year of Gandhi’s birth, event organisers have been asking invited panelists to address the question: “Is Gandhi still relevant?” At school programmes, children have been asking supplementary questions like: “Is there any proof that non-violence still works?” or “Did Gandhi always stick to the truth?” or “Why was he against modern technology?” Answers to such questions are not easy to formulate, but one can sense a common answer in the voices of youth these days.

Three voices from Pondicherry University come to mind. At its 27th convocation held on December 23, 2019, the president of India was the chief guest. A student, Karthika B Kurup, who was to receive a gold medal for obtaining the top rank in M.Sc. in electronic media, decided to boycott the function as a gesture in support of students’ protest in other campuses. She said: “The government must understand how strong the sentiment is by seeing people like me, students, foregoing our valuable, hard-earned moments.” Another student, A S Arun Kumar, who was to receive his Ph.D. decided to miss the convocation because he felt he could not rejoice when so many young people were so angry. A third student to stay away from the convocation was S A Mehala who was to receive her Ph.D. in anthropology. Referring to the protests, she said, “This is why we are educated. We study so we can reason and question”.

No statement about the aim of education could be more succinct. That is why Pondicherry University should feel proud of having such students. More likely, they will be criticised as being politically motivated. Anticipating such criticism, Debsmita Chowdhury, a gold medalist of Jadavpur University, made it clear that she had never been associated with any politics. She tore up a copy of the Citizenship Amendment Act while on the dais to receive her gold medal for topping her subject, international relations. She justified her action by saying that the Act is against humanity and the Constitution.

The statements made by these students carry an unmistakable imprint of Gandhi. His arguments against the exercise of power without adequate moral consideration were quite similar. The students are also reminding us what Gandhi meant by truth. As a word, “truth” is so familiar, and its customary meaning, that is, fidelity to facts, so common, that we seldom stop to consider the purpose it served for Gandhi. He used it as an encompassing ethical concept, a symbolic representation of an amalgam of certain values. Some of these are derived from tradition; others reached him through his education, legal practice and political experience. In the first category, we can recognise values like honesty, gratitude and courage to follow one’s conscience. To the second category belong justice, equality, rule of law and dignity of the individual. The two categories come together in Gandhi’s idea of truth and its association with non-violence.

His statements like “Truth is God” convey, on the one hand, the importance of continuous struggle to pursue these values, and, on the other hand, the necessity of undying faith in them. Why non-violence was so crucial a factor in Gandhi’s politics has to do with the status that truth enjoys in it. If truth is a desirable common pursuit, the struggle it involves cannot be sustained in an atmosphere of violence and fear. The ethical contest Gandhi invites all sides to enter forbids the use of fear: Arousing it is as bad as becoming its victim. The victor must prove moral superiority to the satisfaction of the loser. That is why Gandhi’s politics is essentially an educational activity.

In circumstances when faith in these values is facing repeated blows, it helps to remember and study Gandhi. Indeed, it is hard not to miss Gandhi these days, as a source of solace and the energy to maintain one’s faith in these values. You feel as if someone had imagined our present pain and had worked out a cure for it. It is not easy to articulate the nature of this pain. Those who feel it can’t understand the others who don’t. Our political system is negotiating a difficult bend. There is great volatility everywhere, and the new, speedy technology of communication has exacerbated it.

The terrible clash between competitive nationalist identities that led to the holocaust has not slowed down or stopped. Infected by this competition, India is busy reorganising its self-projection. Gandhi’s attempt to grasp and define the meaning of being Indian faced serious obstacles in society and politics. The values he had used as basic elements of his vision of India’s future faced relentless conflicts. They continue, and so does Gandhi’s search and struggle.

The author is an educationist and a bilingual writer