Book cover of History Men, Jadunath Sarkar, G S Sardesai and Raghubir Sinh and Their Quest for India’s Past

Book cover of History Men, Jadunath Sarkar, G S Sardesai and Raghubir Sinh and Their Quest for India’s Past

Title: History Men, Jadunath Sarkar, G S Sardesai and Raghubir Sinh and Their Quest for India’s Past

Author: TCA Raghavan

Publication: HarperCollins

Pages: 427

Price: Rs 800

The discipline of history is confronted by a paradox today. On one hand, there seems to be a renewed interested in the past, testified by the publication of biographies of personalities who lived a few centuries ago. Though written, by and large, for the non-academic audience, such literature can stand scrutiny and the test of historical methods. Cinema, too, has drawn on themes and episodes in history, though its fidelity to research remains questionable. It seems to feed into the other aspect of the paradox – the evocation of history in ideological battles. Of course, the past has rarely been a territory unaffected by the predilections of the present. But a difference ought to be made between professionals trained in the nuances of the discipline and those who trace genealogies of plastic surgery to elephant deities or reduce personalities of yore to communally-loaded caricatures.

The three protagonists of the work under review would have found this situation interesting. TCA Raghavan’s History Men is about a trio with a commitment to writing history with the conviction that the study of the past had a value in itself. It’s about the friendship between three medievalists, two of them rather well-known and closer in years, Jadunath Sarkar and GS Sardesai, and the lesser-known and younger Raghubir Sinh. It was friendship that began, rather appropriately, in the quest for sources of the past.

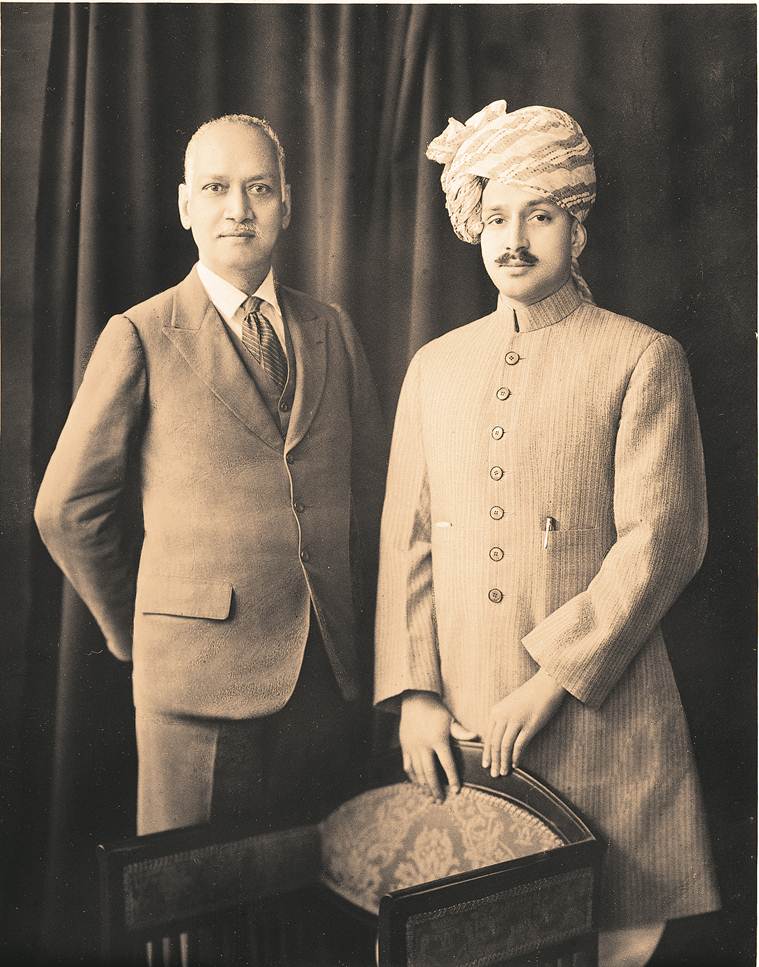

Jadunath Sarkar and Raghubir Sinh in a photo from December 1937. (Courtesy: HarperCollins)

Jadunath Sarkar and Raghubir Sinh in a photo from December 1937. (Courtesy: HarperCollins)

Sarkar, whose felicity with Persian sources was well-known in the early years of the 20th century, received a suggestion from his colleague, Gopal Rao Deodhar, that a knowledge of Maratha sources would be useful for his research. He was directed to Sardesai with the suggestion that the association would prove mutually beneficial: to Sarkar for Maratha documents and to Sardesai for Mughal and Persian sources. The two corresponded first in 1904 and met in 1909. The five-decade long friendship between the ‘Mughal’ and the ‘Maratha’ was important in locating new sources and enriching the knowledge of the late 17th, 18th and 19th centuries.

The third figure in this triad is Maharajkumar Raghubir Sinh, “scion and heir to the small princely state of Sitamau in Central India”. The heir to a princely state, wanting to conduct serious historical research, writes Raghavan, was unusual for the times. Sinh became Sarkar’s student in the 1920s and the relationship turned to friendship after the Rajput scion submitted his thesis to the Agra University, ‘Malwa in Transition or a Century of Anarchy (1698-1766)’. Through his mentor, he was drawn to Sardesai and became an equal participant in the endeavours of his seniors — Sinh, committed to the widest dissemination of history, wrote in Hindi, and founded a public library. For historiography, this association meant the enlivening of the Mughal, Maratha and Rajput interface during a time of immense political flux in the country.

The pursuits of the trio inevitably linked with a particularly fraught aspect of Indian historiography. They wrote at a time when history was beginning to get caught up in ideological positions. Sarkar’s understanding of Aurangzeb’s bigotry has come to be regarded as the forebearer of communal history. But the historian’s unequivocal fidelity to his sources has been acknowledged by even his most trenchant critics. “National history,” he wrote in a letter to Rajendra Prasad, “like every other history of the name and deserving to endure must be true as regards the facts and reasonable in the interpretation of them. It will be national not in the sense that it will try to suppress or whitewash everything in our country’s past which must be disgraceful, but because it will admit them, and, at the same time, point out that there were other and nobler aspects in that stage of our nation’s evolution, which offset the former.”

But Sarkar’s unrelenting pursuit of facts could be deemed “politically incorrect” in his times and his assessment of Aurangzeb was viewed as divisive and negative. It seems that the reception made Sarkar bitter towards a large section of his professional community. He avoided the Indian History Congress, though he was invited to it on more than one occasion — in fact, he was once elected president in absentia, a post which he spurned. Sardesai and Sinh, in contrast, delivered presidential lectures to the History Congress. Sarkar, in fact, on one occasion, was rather caustic about Sardesai’s optimism about the History Congress’s ability to bring the Jaipur royal archives to the light of the day.

There were other instances when these historians differed. Sinh’s views on the Marathas in Malwa, for example, was at difference with that of Sardesai’s. The Maratha expansion, he argued, was because of their superior military force rather than any sense of religious affinity with the Rajputs. “What is interesting,” writes Raghavan, is “how on account of these different perspectives, the same manuscript source was read differently by the two historians — an excellent introduction of an essential feature of history writing”.

With history writing rightly forsaking its Rankean approach to political history, the works of the trio were overtaken by social and economic histories. Interestingly, this seems to have exonerated Sarkar, at least implicitly, of communal inclinations — his fault, instead, was emphasising too much on the frailties of personalities. With Sardesai and Sinh, he shared a single-minded pursuit of facts. The History Men animates this quest. It showcases three historians cooperating, debating and disagreeing in order to hone their craft — that’s something that should be salutary to today’s conversations about the past as well.