A dull white marble plaque on one column of the main entrance of the house reads ‘Hassan Suhrawardy’ in black lettering (Photo: Neha Banka)

A dull white marble plaque on one column of the main entrance of the house reads ‘Hassan Suhrawardy’ in black lettering (Photo: Neha Banka)

In the summer of 2017, a right-wing publication in India published a widely-shared article with the dramatic headline: “It’s A Crying Shame That ‘The Butcher Of Bengal’ Has A Road Named After Him In Kolkata”. The “Butcher” in question was Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy, whom the publication accused of engineering the “killings, maiming, rape and molestation of tens of thousands of Hindus in Calcutta back in 1946”. The publication demanded that the long stretch of road named Suhrawardy Avenue in south Kolkata be renamed. The catch was, the publication had picked on the wrong Suhrawardy.

For the road had not been named after Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy at all, but rather his uncle Hassan Shaheed Suhrawardy, who was among his many abilities, a Bengali diplomat, scholar and art-critic, but certainly not the ‘Butcher of Bengal’.

Hassan Suhrawardy (Photo credit: Wikipedia Commons)

“It is high time the name of the road is changed. Bengal does not lack heroes, and it is high time one of them is honoured instead of a criminal who caused so many deaths and such destruction in the city,” stated the article and went on to list the many crimes against humanity purportedly committed by Suhrawardy in detail.

It was hardly the first time that such demands to change the road’s name had been proposed. Some seven years ago, a petition on change.org was launched by a user, directed to the Government of Bengal, asking why “a communal minded anti-Indian” should have a road named after him.

Cases like these particularly highlight the necessity and importance of historical information and context, especially in the fraught socio-political climate of today’s India. The Suhrawardys were a prominent, wealthy family in Bengal during the British occupation of India and comprised of intellectuals who made significant contributions to political developments during India’s freedom struggle. In the book ‘Bengal Divided: Hindu Communalism and Partition, 1932-1947’, author Joya Chatterjee writes that the Suhrawardys were a “leading ashraf family of Bengal, which claimed ancestry going back to the first caliph”. In Islam, Abu Bakr was the first caliph and the father-in-law of the Prophet. Those who trace their lineage to the Prophet through Abu Bakr call themselves Ashrafs.

According to Chatterjee, the Suhrawardys did well for themselves during the 20th century because of the opportunities that the British had made available for “adept Muslims”. The family has a long line of well educated members, a list that includes surviving descendants in the present day.

Also Read | Streetwise Kolkata: Tiretta Bazaar, a Chinatown named after an Italian

Hassan Suhrawardy became the first Muslim Vice-Chancellor of Calcutta University. His sister, Khujastha Akhtar Banu was married to her cousin Justice Zahid Suhrawardy, a judge at the High Court at Calcutta and their son, Huseyn Suhrawardy was a noted lawyer and politician and an active member of the Muslim League. He went on to become the fifth Prime Minister of Pakistan and also acquired the name ‘Butcher of Bengal’ for his role in instigating communal riots in Bengal that led to one of the bloodiest days in the history of the country—Direct Action Day—on August 16, 1946. The uncle and nephew from the same family, with similar sounding names could not have been more different.

Huseyn Suhrawardy (Photo: National Portrait Gallery)

Huseyn Suhrawardy (Photo: National Portrait Gallery)

The Suhrawardy family’s prominence and their contributions, both positive and negative, in the subcontinent’s socio-political history is not challenging to find but requires the determination to conduct rudimentary research in the quest to publish truthful information.

The Calcutta Municipal Gazette of March 1933 mentions that the Calcutta Municipal Corporation held a meeting on March 8, 1933 and decided to christen as Suhrawardy Avenue “the new (100 ft.) road constructed by the C.I.T. (Calcutta Improvement Trust) from Park Circus to the junction of Kasaipara Lane (and lying north of the Park) on which stands the house of Sir Hassan Suhrawardy, Vice-Chancellor of the Calcutta University”. The new name of the road was notified through the Calcutta Municipal Gazette on April 20, 1933.

Park Circus is a predominantly Muslim neighbourhood with more residential and public buildings than commercial enterprises. The seven-point crossing and the large A.J.C. Bose road flyover in the neighbourhood serves to connect the city of Kolkata with the East Kolkata wetland area, the neighbourhoods of Salt Lake, Tangra, Topsia, the rapidly developing suburbs of the metropolis and the airport beyond. As a result, regardless of the time of day, it is also one the most chaotic junctions in the city

Also Read | Street-wise Kolkata: How Park Street got its name

Park Circus is a predominantly Muslim neighbourhood with more residential and public buildings than commercial enterprises. (Photo: Neha Banka)

Park Circus is a predominantly Muslim neighbourhood with more residential and public buildings than commercial enterprises. (Photo: Neha Banka)

In the constant chaos of Park Circus, it took some time to find Sir Hassan Suhrwardy’s house. Most of the old buildings in the neighbourhood have been replaced with unappealing modern construction, devoid of history and characteristics. The greenery on what was once a tree-lined avenue is now diminished.

In the constant chaos of Park Circus, it took some time to find Sir Hassan Suhrwardy’s house (Photo: Neha Banka)

In the constant chaos of Park Circus, it took some time to find Sir Hassan Suhrwardy’s house (Photo: Neha Banka)

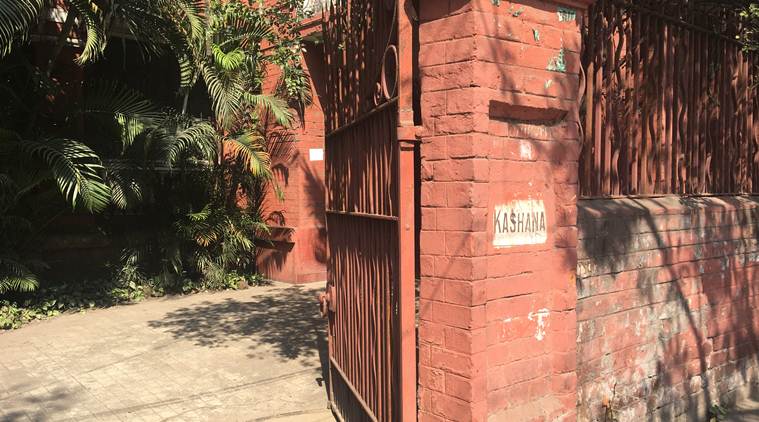

A few minutes from Arsalan, the famous biryani joint, towards Don Bosco School, is an old red brick building constructed in the colonial tropical style with Islamic architectural design influences, interspersed with patches of forest green, the former home of Sir Hassan Suhrawady. The building, the facade of which is almost hidden behind foliage and billboards, is a two-storey structure and today houses the Bangladesh High Commission Library and Information Center.

A dull white marble plaque on one column of the main entrance of the house reads ‘Hassan Suhrawardy’ in black lettering while the other reads ‘Kashana’.

Like most residential mansions built during colonial India, Suhrawardy’s home also has two main gates that served as entry and exit points on the same side. Another similar white plaque on the exit gate has Urdu lettering in black that also reads ‘Kashana’; meaning ‘ghar’, ‘home’.

The exit gate has Urdu lettering in black that also reads ‘Kashana’; meaning ‘ghar’, ‘home’ (Photo: Neha Banka)

The exit gate has Urdu lettering in black that also reads ‘Kashana’; meaning ‘ghar’, ‘home’ (Photo: Neha Banka)

Given the placement of the plaques on two adjacent pillars, perhaps they were deliberately placed so; to be read as ‘Suhrawardy’s Home’. On the exterior of the portico facing the road is a signboard in deep green that reads Bangladesh High Commission Library and Information Center. If a passer-by on the road were to attempt to read the signboard or even photograph the old building, the view would be obstructed by a large PVC billboard of a smiling Mamata Banerjee, the leader of the state of West Bengal.

PVC billboard of a smiling Mamata Banerjee outside the building (Photo: Neha Banka)

PVC billboard of a smiling Mamata Banerjee outside the building (Photo: Neha Banka)

The top floor of the building has architectural design elements similar to the Arabic mashrabiya, without enhanced projections commonly seen in bay windows, and partial lattice work in brick is painted white. The fronds of tall palm trees growing inside the boundary walls of the house provide it cover and stand in contrast to the brick red exterior.

Red oxidised floors that were once a common sight in Calcutta residences, now exceedingly rare in the city, form the surface of a small flight of stairs to the entrance of the library. Old doors that must have once allowed access to the interiors of the Suhrawardy home have been stripped and replaced with a modern alternative, easy to maintain, with dirty glass panels through which nothing can be seen. The doors open to a large life-size black and white portrait of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, the first President of Bangladesh, who went on to later also serve as Prime Minister.

The doors open to a large life-size black and white portrait of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, the first President of Bangladesh, who went on to later also serve as Prime Minister. (Photo: Neha Banka)

The doors open to a large life-size black and white portrait of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, the first President of Bangladesh, who went on to later also serve as Prime Minister. (Photo: Neha Banka)

Just above that is another smaller framed portrait of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, below which is one of Sheikh Hasina, the current Prime Minister of Bangladesh, Rahman’s daughter. Also present is a photograph of current President of Bangladesh Abdul Hamid. A signboard beneath the portraits in Bangla says ‘Reading Room’, pointing to a boarded door that is at present closed. The ground floor of the house has been sectioned off to hold rows of books in the Bangla language, on everything pertaining to Bangladesh. A librarian sits behind a large desk in one room but doesn’t know much about the building’s history.

The history of the sub-continent remembers the two men of the Suhrawardy family very differently, depending on who is telling the story. Hassan Suhrawardy was the second Muslim from the Indian sub-continent to become a Fellow of the Royal College of Surgeons of England.

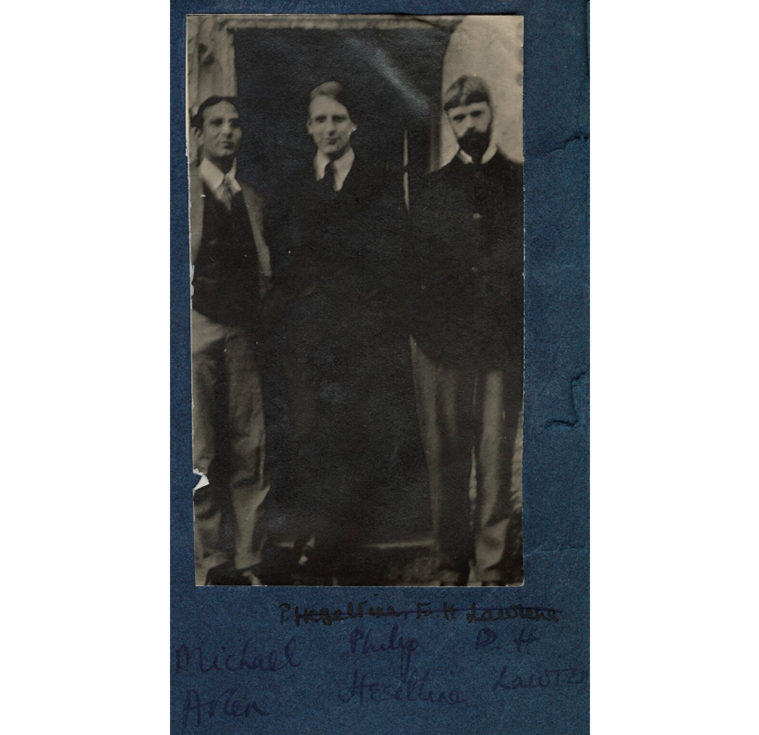

Hassan Shahid Suhrawardy standing with British music composer Philip Arnold Heseltine (pseudonym, Peter Warlock) and author D.H. Lawrence. According to the National Portrait Gallery, this photograph was taken by Lady Ottoline Morrell at the Garsington Manor, Oxfordshire, UK, in November 1915. (Photo credit: National Portrait Gallery)

Hassan Shahid Suhrawardy standing with British music composer Philip Arnold Heseltine (pseudonym, Peter Warlock) and author D.H. Lawrence. According to the National Portrait Gallery, this photograph was taken by Lady Ottoline Morrell at the Garsington Manor, Oxfordshire, UK, in November 1915. (Photo credit: National Portrait Gallery)

In 1945, he began teaching Islamic History and Culture at Calcutta University and served as Chair of Public Health and Hygiene at the institution. Among his many roles in the social and political scape of Bengal, he also founded the East Indian Railways’ ambulance and nursing division.

While Vice-Chancellor of the University of Calcutta, in 1932, he acquired his knighthood and the title of ‘Sir’ by chance after saving the life of Governor Stanley Jackson while a Calcutta University student and Indian revolutionary Bina Das opened fire at him on the grounds of the university. For the remainder of his life, he remained a member of the Muslim League. A month before his death in 1946, he renounced his knighthood, the Order of the British Empire. Suhrawardy had dedicated his life to medicine, education and public service.

In contrast, Huseyn Suhrawardy is remembered for his infamy. After studying at St. Xavier’s College, Huseyn Suhrawardy attended Oxford University where he read Political Science and Law. After his graduation from Oxford, Suhrawardy was called to bar at the Gray’s Inn, one of the four Inns of Court in London, where he trained to be a barrister-at-law. After his return to Calcutta, Huseyn Suhrawardy used his legal expertise to champion the causes he believed in, including the Khilafat Movement and the Pakistan Movement.

In 1943, he was appointed to lead the Ministry of Civil Supply that coincided with the famine of 1943. While many historians lay the blame of the famine directly on the head of Winston Churchill, there are others who accuse Suhrawardy of having caused it or of having prior information of the possibility of the famine but doing nothing to prevent it. Another group of historians believe that Suhrawardy’s aggressive policy measures caused even more difficult circumstances, resulting in the death of millions of ordinary people.

In August 1946, Suhrawardy and several other leaders of the Muslim League were accused of delivering provocative speeches, stoking communal clashes and division on religious lines. On August 16, 1946, what came to be known as Direct Action Day, one of the most violent dates in the history of the nation, riots broke out in Calcutta and in other parts of Bengal between Hindus and Muslims. Critics accuse Suhrawardy of not doing enough to stop the violence and of further stoking communal tensions through continued provocation and deliberate interference with police duties that were aimed at controlling the disturbances.

After the Partition of India in 1947, Suhrawardy remained in Calcutta for two years before eventually moving to Pakistan in 1949, where his political career did not suffer greatly. In 1956, he became the Prime Minister of Pakistan, a post he retained only for one year. In 1960, he retired from politics and left Pakistan for Beirut, Lebanon, where he died of cardiac arrest in 1963.

There were no records available for verification, but perhaps the entire Suhrawardy family lived in the same complex prior to the Independence of India. The Kolkata Municipal Corporation has designated Suhrawady’s house as a protected heritage building and the Bangladesh High Commission looks after the basic upkeep of the premises. According to Md. Mofakkharul Iqbal, First Secretary, Press Wing, Deputy High Commission of Bangladesh, today the Waqf board owns Suhrawardy’s house that the Bangladesh government uses on lease.

Perhaps sometime after Huseyn Suhrawardy left for Pakistan in 1949, the ownership of the house was transferred to the Waqf board but there were no records immediately available and the Deputy High Commission of Bangladesh did not have information regarding property rights or even detailed information concerning the history of what was formerly the Suhrawardy residence.

A 15-minute drive on a low-traffic day, and a stone’s throw from the two La Martinere Schools on Rawdon Street, is another red brick building where Hassan Suhrawardy stayed on rent for an extended period of time. Md. Mofakkharul Iqbal at the Deputy High Commission of Bangladesh is aware of the historical importance of the site where a shopping complex now stands but does not have more information to offer. The heritage status of this building was disputed and sometime during the last decade, a local real estate developer managed to secure the land’s rights from the Kolkata Municipal Corporation to demolish the structure and replace it with yet another shopping complex.

Somewhere in the annals of India’s history, many have forgotten about the Suhrawardy family. The descendants of the Suhrawardy family are spread across the world from Pakistan to Jordan. The house on Rawdon Street where Hassan Suhrawardy once lived does not exist any more. Inside the complex of the building that is now the Bangladesh High Commission Library and Information Center, there are no images of Hassan Suhrawardy. The Suhrawardys do not live here anymore.