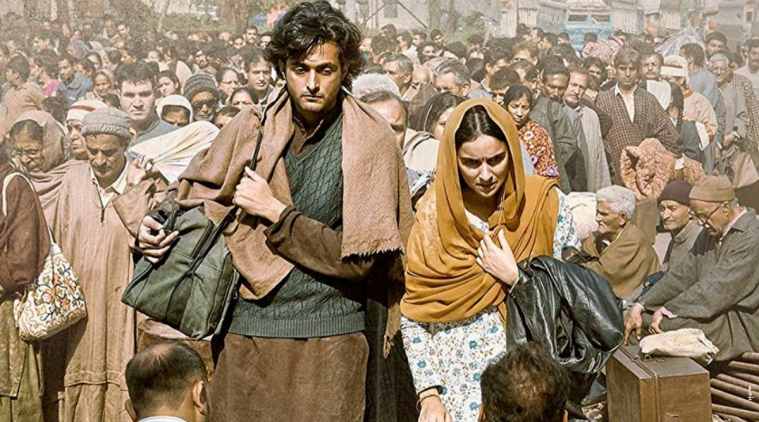

A still from Vidhu Vinod Chopra’s film Shikara.

A still from Vidhu Vinod Chopra’s film Shikara.

Writer-director Vidhu Vinod Chopra on the film Shikara, his connect with Kashmir, the Pandit exodus and why the only solution to hate is love.

You have been working on a movie on Kashmiri Pandits for 12 years. Why did you take so long to make Shikara?

I started work on Shikara after the demise of my mother (Shanti Devi Chopra) in 2007. It’s a tribute to her. The Kashmiri Pandit exodus is a known issue but the complexities and the events that led to it are not known. This movie required significant research so that we could tell an engaging story, which helps in bringing this conversation to the fore. This was perhaps my most challenging work as I had to remain dispassionate to depict the truth and yet make a compelling argument that the only solution to hate is love and that is at the centre of my movie. The love between Shiv Kumar Dhar (played by Aadil Khan) and Shanti Dhar (Sadia) forces us to think beyond hate. The shooting was done mostly in Kashmir, which was under heavy security. The writing also took time as I had to sift through tons of documentation and video footage to bring reality to celluloid.

To what extent did your mother’s memory of Kashmir and her life influence you?

In 1989, my mother came to Bombay for the premiere of my film Parinda, but couldn’t go back to Kashmir. Shikara is about her home, my home and how we lost that home. So, it’s a deeply personal story. Despite all that, she only had love for the people, the valley, our home, and that love truly overpowered every other emotion — be it disappointment, anger or loss. That’s why I made this movie. The other important aspect is that people across the world need to know what led to the Pandit exodus. The aim was to give their suffering and sheer neglect, a platform.

How much do you borrow from your personal life, family and friends, for Shikara?

I have lived in and experienced a heaven on earth called Kashmir. I was born and raised in the valley, I saw the political and ideological shift first hand. I could sense the scenarios changing but never ever imagined that it would lead to driving out of an entire community. The pain cannot be explained when people had to leave everything and run for their lives within minutes.

Friends turned foes overnight. Fundamentalism overpowered people’s connection and love for each other. External forces drove the agenda and brought death and destruction in the valley. I have lived through the pain. Hence, most of what you will see in the movie are my personal experiences told through the eyes of Shanti the character, and also Shanti my mother. I also had Rahul Pandita, whose book Our Moon has Blood Clots (Penguin, 2013), is a narration of the horror of the exodus and documentation of several stories. Screenwriter Abhijat Joshi also worked with me.

You showed the film to Kashmiri Pandits. How do they look back at the events of 1990s?

The film screenings have left them speechless. I could see emotions of anger, betrayal, nostalgia and pain of leaving their beloved Kashmir but they were hopeful that this movie will tell their story, of grit and determination and love, and that things will resolve. The movie shows how we should engage in samvad (discussion) and not vivad (disagreement).

Do you see things changing after the abrogation of Article 370? Do you see any real prospect of Kashmiri Pandits returning to their native land?

For 70 years, we had Article 370. It did nothing good for the people, the economy and their overall well-being. Now, the current government has shown courage and removed Article 370 to bring these regions into the mainstream. Let us see what it does. I want to see Kashmiri Pandit’s return with dignity and pride to their homeland and their status restored.

Do you think that the state administration and subsequent governments — both at the state and centre — have failed Kashmiri Pandits?

It deeply saddens me and leaves me angry that successive governments, media, civil society, and intellectuals have turned a blind eye to the Kashmiri Pandit issue. The insurgency and our inability to handle the internal conflict within Kashmir, kept the focus on Kashmir as a troubled state. So, the question of their return was lost in discussion. Had the Kashmiri Pandits returned, the region would have been better, more peaceful, and economically powerful because local people want communities to come together.

You have shot with real refugees. How do they look back at their displacement? Are they still yearning to go back home?

Yes, I shot with real Kashmiri Pandit refugees for Shikara because I wanted the film to look real. If I was to cast artistes from Mumbai to play the refugees, the film would lose its authenticity. It was incredibly generous of the inhabitants of Jagti refugee camp and all the other camps, to agree to be part of this film. They spent days and nights in difficult conditions. They were more driven than me. They look at this movie with renewed hope that finally someone will hear their plight and pave a path for their return. They want to be home.

For full interview, visit www.indianexpress.com