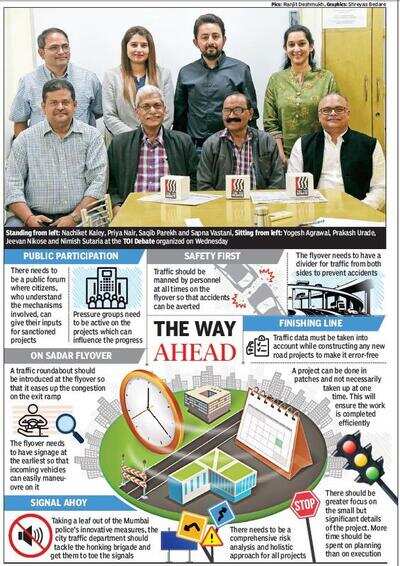

Infrastructure project announcements are never in short supply in the city — most of them grand enough to catch the eye. But the proof is in the pudding, and the recent Sadar flyover landing mess has highlighted the broad-as-daylight gap between project planning and successful execution. Panellists at the TOI Debate discuss how and why Nagpur’s project designs are incommensurate with ground reality

The demographics, underlying cultural strands and social issues of a city, must be at the heart of its project planning studies, believes architect Sapna Vastani. The way new projects shape up though makes one seriously doubt if these aspects are accorded any attention, she feels. Citing the example of areas like Manish Nagar, where hawker zones were not a part of the plan, she wonders why the powers-that-be do not learn from their mistakes.

Chartered accountant Nimish Sutaria finds many of the city’s original master plans astute but feels that their purpose is not well understood today, due to which they are being abused (encroachment of playgrounds being a case in point). “Why do we have so many hospitals in an already congested area like Dhantoli? Why aren’t we spreading out when we have enough space?” he says.

The prime stumbling block, responds former NMC chief engineer Prakash Urade, is the road width availability. “With no scope to increase the width of roads, we are often unable to accommodate plan revisions even if we want to,” says retired public works department (PWD) engineer Jeevan Nikose. The increasing floor space index (FSI) — which is a measure of the city’s population density — further compounds matters as the plan needs to be revised repeatedly to meet the changing needs.

Width is not the only thing that is wrong with roads. The levelling of newly-constructed cement roads is a big area of concern, as per Vastani. “We never experienced severe waterlogging in Nagpur earlier. The drainage system is not being properly looked into,” she says.

Vastani also finds the process of piling layer-after-layer on roads illogical when there is the option of building new roads instead. “It is not very easy to do that, as the soil erodibility factor (also known as the ‘K factor’) gets disturbed by it,” counters Urade.

Architect Priya Nair finds potholes to be a teething issue which affects the discharge rate of traffic, with haphazard management at busy intersections adding to the woes. “Junctions like Medical Square and Ram Nagar Square have traffic coming in from all four sides at once, causing utter chaos,” says businessman Yogesh Agrawal.

Projects keep getting greenlit with scarce planning for the small, key details, according to Sutaria. “There is no provision for last-mile connectivity. Public vehicles have no designated space for parking at the airport. Parking space is not available at any of the brand new Metro stations either,” he claims.

Nachiket Kaley, founder member of non-governmental organization (NGO) Civic Action Guild (CAG), agrees with Sutaria. “The planning occurs on a broad level. We do not work on the details. There is a lot of ambiguity in the minutiae of project implementation, since the documentation is often quite flawed,” says Kaley.

Businessman Saqib Parekh feels that there is no vision to assimilate rural and urban planning, and that the city needs short, five-year-long plans more than a 30-year vision statement for development to materialize. “Rural-urban coordination is conspicuous by its absence. Civic work is concurrently undertaken by different sets of employees, with scant regard for the big picture,” says Nikose.

Sutaria believes that there is a “multiplicity of cooks” that spoils many plans. Standard operating procedures are often found lacking, chimes in Kaley.

“The Japanese allocate 90% of the project time to planning, and 10% to execution. That is what makes the difference,” states Urade. “When a project is announced, it is not just the technical team’s prerogative to work on it. Everyone, including financers, architects and hawkers need to be involved in it,” he says.

The need for connecting projects to people finds the panel’s consensus. “Planners need to make projects people-friendly,” says Nikose. Nair feels that taking feedback from common people before going ahead with the project is necessary.

“The problem needs to be discussed holistically. Pressure groups can be instrumental in driving attention towards critical issues,” Urade adds.

Managing inputs from so many stakeholders, however, comes with its own challenges. “All engineers and planners come with their own perceptions, which may not align with those of others,” says Agrawal. To add to that, change is “very drastic” in today’s times, as per Nikose, which makes it tough for engineers to stay abreast.

A solution to that could be taking up project work in patches, suggests Kaley. “This would ensure that even if the scale of a project is small, it is done well,” he explains.

The panel also has some solutions for the Sadar flyover landing mess, which includes signalling and surveillance at the flyover, with traffic police personnel to man it at all times.

Not everyone agrees with these propositions. “What is the use of a flyover if one needs to halt in between?” says Sutaria. “The flyover should be permanently divided with a non-rigid divider,” he suggests.

Vastani wants efficient routing of traffic and signage to be put up at Sadar flyover. “There should be comprehensive risk analysis of the project, after which the process of ideation should commence,” Urade signs off.

The demographics, underlying cultural strands and social issues of a city, must be at the heart of its project planning studies, believes architect Sapna Vastani. The way new projects shape up though makes one seriously doubt if these aspects are accorded any attention, she feels. Citing the example of areas like Manish Nagar, where hawker zones were not a part of the plan, she wonders why the powers-that-be do not learn from their mistakes.

Chartered accountant Nimish Sutaria finds many of the city’s original master plans astute but feels that their purpose is not well understood today, due to which they are being abused (encroachment of playgrounds being a case in point). “Why do we have so many hospitals in an already congested area like Dhantoli? Why aren’t we spreading out when we have enough space?” he says.

The prime stumbling block, responds former NMC chief engineer Prakash Urade, is the road width availability. “With no scope to increase the width of roads, we are often unable to accommodate plan revisions even if we want to,” says retired public works department (PWD) engineer Jeevan Nikose. The increasing floor space index (FSI) — which is a measure of the city’s population density — further compounds matters as the plan needs to be revised repeatedly to meet the changing needs.

Width is not the only thing that is wrong with roads. The levelling of newly-constructed cement roads is a big area of concern, as per Vastani. “We never experienced severe waterlogging in Nagpur earlier. The drainage system is not being properly looked into,” she says.

Vastani also finds the process of piling layer-after-layer on roads illogical when there is the option of building new roads instead. “It is not very easy to do that, as the soil erodibility factor (also known as the ‘K factor’) gets disturbed by it,” counters Urade.

Architect Priya Nair finds potholes to be a teething issue which affects the discharge rate of traffic, with haphazard management at busy intersections adding to the woes. “Junctions like Medical Square and Ram Nagar Square have traffic coming in from all four sides at once, causing utter chaos,” says businessman Yogesh Agrawal.

Projects keep getting greenlit with scarce planning for the small, key details, according to Sutaria. “There is no provision for last-mile connectivity. Public vehicles have no designated space for parking at the airport. Parking space is not available at any of the brand new Metro stations either,” he claims.

Nachiket Kaley, founder member of non-governmental organization (NGO) Civic Action Guild (CAG), agrees with Sutaria. “The planning occurs on a broad level. We do not work on the details. There is a lot of ambiguity in the minutiae of project implementation, since the documentation is often quite flawed,” says Kaley.

Businessman Saqib Parekh feels that there is no vision to assimilate rural and urban planning, and that the city needs short, five-year-long plans more than a 30-year vision statement for development to materialize. “Rural-urban coordination is conspicuous by its absence. Civic work is concurrently undertaken by different sets of employees, with scant regard for the big picture,” says Nikose.

Sutaria believes that there is a “multiplicity of cooks” that spoils many plans. Standard operating procedures are often found lacking, chimes in Kaley.

“The Japanese allocate 90% of the project time to planning, and 10% to execution. That is what makes the difference,” states Urade. “When a project is announced, it is not just the technical team’s prerogative to work on it. Everyone, including financers, architects and hawkers need to be involved in it,” he says.

The need for connecting projects to people finds the panel’s consensus. “Planners need to make projects people-friendly,” says Nikose. Nair feels that taking feedback from common people before going ahead with the project is necessary.

“The problem needs to be discussed holistically. Pressure groups can be instrumental in driving attention towards critical issues,” Urade adds.

Managing inputs from so many stakeholders, however, comes with its own challenges. “All engineers and planners come with their own perceptions, which may not align with those of others,” says Agrawal. To add to that, change is “very drastic” in today’s times, as per Nikose, which makes it tough for engineers to stay abreast.

A solution to that could be taking up project work in patches, suggests Kaley. “This would ensure that even if the scale of a project is small, it is done well,” he explains.

The panel also has some solutions for the Sadar flyover landing mess, which includes signalling and surveillance at the flyover, with traffic police personnel to man it at all times.

Not everyone agrees with these propositions. “What is the use of a flyover if one needs to halt in between?” says Sutaria. “The flyover should be permanently divided with a non-rigid divider,” he suggests.

Vastani wants efficient routing of traffic and signage to be put up at Sadar flyover. “There should be comprehensive risk analysis of the project, after which the process of ideation should commence,” Urade signs off.

Get the app