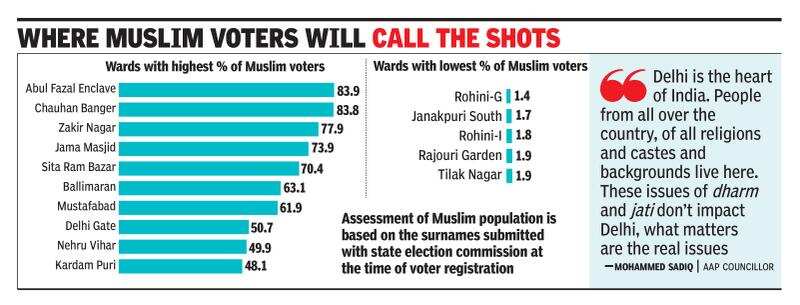

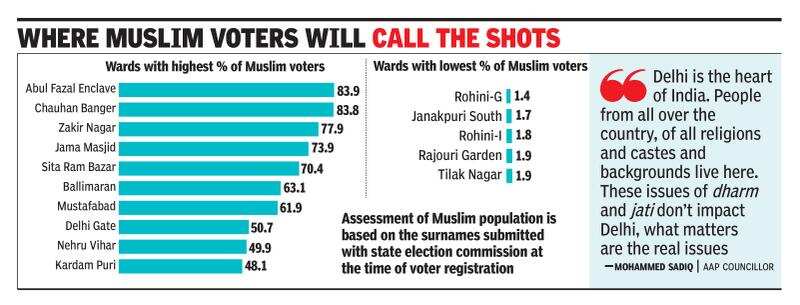

NEW DELHI: In polarised times, three is a crowd. Fully aware of the perils of a triangular contest, the capital’s 25 lakh Muslims who want to hold back BJP know they have to choose between AAP and Congress.

“Sabka apna rujhan hota hai, but the wave seems to be for AAP,” says 70-year-old Mohammed Tehsin, a vendor from Mustafabad in northeast Delhi. He has voted for Congress his whole life, including in the last Lok Sabha election, but most of the neighbourhood is voting for AAP, he says. “It is difficult to choose in the voting booth, ungli dagmaaga jaati hai, but it is important to make a clear decision,” he says.

Two boys on a bike speak up loudly for Congress, pointing out that the candidate’s father, Hasan Ahmed, had built these roads and the nearby graveyard, and had worked hard. But they also admit they would probably persuade their families to vote for AAP so that the community’s vote could be ektarfa. Last time, BJP had coasted to power with 58,388 votes in the constituency, which was split between Congress at 52,357 and AAP at 49,791.

While Congress has leapt in to defend Muslims in the CAA-NRC resistance and police excesses, AAP has steered largely clear of the issue.

Even at Batla House chowk near Jamia Millia Islamia, one of the epicentres of the recent violence, there is more vocal support for AAP. While Nasim Ahmed, a Congress supporter, claims that his candidate, Parvez Hashmi, “has never lost an election from here, and has done most of the work to build the area”, he is outnumbered by the others, who say that Congress has not put up a damdaar CM candidate this time. “In the 2015 elections, when AAP won, it was all decided in the last three days, paasa palat gaya. This time though, the leher is clearly with Arvind Kejriwal,” says Aas Mohammed. Many of these men used to work at a 30-year-old steel fabrication business that shut down, because of GST and rising costs.

Voters are eloquent on the dangers of NRC and CAA, of Modi government’s economic record, its sale of PSUs, and so on. This, however, is an existential crisis, they say. “It is only the bhaichaara of old that now sustains us, the nai fasal does not seem to understand that,” despairs Aas Mohammed. But this struggle for the Constitution, it is larger than the Delhi elections, he says.

Sitting on the steps of Jama Masjid at a protest against CAA-NRC, 34-year-old Nida (who doesn’t want to share her last name), says: “Matia Mahal will see a sweep for jhadoo — I say this with 98% confidence.”

AAP candidate Shoaib Iqbal has just hopped over from Congress and commands great clout in the area, having won every election (except the last) under various party banners. “My father is a kattar Congressi, but even he understands, why waste a vote this time,” she says.

In nearby Ballimaran, AAP MLA and minister Imran Hussain, a businessman who was an independent councillor before joining the party, is visibly popular. His office handles Aadhaar cards, ration cards, caste certificates and other paperwork, hospital referrals, and so on. “We have a daily footfall of 300-400 people here, and 10 staff members. Meanwhile, Congress candidate Haroon Yusuf (former minister and party heavyweight who had been elected five times from Ballimaran) does not even have an office in the neighbourhood,” claims AAP councillor Mohammed Sadiq.

He is dismissive about BJP’s polarisation campaign. “Delhi is the heart of India. People from all over the country, of all religions and castes and backgrounds live here. These issues of dharm and jati don’t impact Delhi, what matters are real issues”. AAP volunteers claim to have constructed 100 borewells, and replaced 80% of the sewerage network in the area. There is a mohalla clinic close by, and three schools are being built. “The borewell work began with Haroon Yusuf, he has also worked. But with him, ek- zamana-tha wali baat ho gayi — I think he should have sat out this election,” says Mohammed Asif, who runs a spectacles shop in Ballimaran.

He makes a clear distinction between the Lok Sabha election, where “bigger internal and international issues matter”, and this one, which is about service delivery, about gullies and sewers, water and electricity, schooling and health. AAP has worked hard on all fronts, he says. Fees have been waived for minority students who can produce an income certificate, says Nazma Bari, an ad hoc teacher in a municipal school in Matia Mahal.

For many voters, it is not just a tactical choice between the Lok Sabha and Vidhan Sabha, there is a genuine satisfaction with AAP’s redistributive work. The slashing of electricity and water bills means more to the poor than abstract “development” work like flyover-construction that Sheila Dikshit used to talk up, they say. “I used to pay Rs 1,000-1,200 for electricity, Rs 2,500-3,000 sometimes for water. Now, it is nothing. I also got my GPS SIM free,” says Zamir Ahmed, an auto driver.

Meanwhile, an e-rickshaw driver, Mohammed Salim says that his 80-year-old mother sends duas for Arvind Kejriwal. “He won my heart when he spoke about getting corrupt officials suspended. He gets the pain of ordinary people.”

In northeast Delhi’s Seelampur, young Mohammed Javed, a tailor, says there is no contradiction between supporting Congress and AAP — “this time, it’s definitely Kejriwal for many of us”. His friend, Amit Verma, is an ardent BJP supporter, and they rag each other mercilessly over politics. “He’s a worm, but I love him,” says Javed. “We don’t fight, only stupid people are made to fight over religion and politics,” says Verma.

“Sabka apna rujhan hota hai, but the wave seems to be for AAP,” says 70-year-old Mohammed Tehsin, a vendor from Mustafabad in northeast Delhi. He has voted for Congress his whole life, including in the last Lok Sabha election, but most of the neighbourhood is voting for AAP, he says. “It is difficult to choose in the voting booth, ungli dagmaaga jaati hai, but it is important to make a clear decision,” he says.

Two boys on a bike speak up loudly for Congress, pointing out that the candidate’s father, Hasan Ahmed, had built these roads and the nearby graveyard, and had worked hard. But they also admit they would probably persuade their families to vote for AAP so that the community’s vote could be ektarfa. Last time, BJP had coasted to power with 58,388 votes in the constituency, which was split between Congress at 52,357 and AAP at 49,791.

While Congress has leapt in to defend Muslims in the CAA-NRC resistance and police excesses, AAP has steered largely clear of the issue.

Even at Batla House chowk near Jamia Millia Islamia, one of the epicentres of the recent violence, there is more vocal support for AAP. While Nasim Ahmed, a Congress supporter, claims that his candidate, Parvez Hashmi, “has never lost an election from here, and has done most of the work to build the area”, he is outnumbered by the others, who say that Congress has not put up a damdaar CM candidate this time. “In the 2015 elections, when AAP won, it was all decided in the last three days, paasa palat gaya. This time though, the leher is clearly with Arvind Kejriwal,” says Aas Mohammed. Many of these men used to work at a 30-year-old steel fabrication business that shut down, because of GST and rising costs.

Voters are eloquent on the dangers of NRC and CAA, of Modi government’s economic record, its sale of PSUs, and so on. This, however, is an existential crisis, they say. “It is only the bhaichaara of old that now sustains us, the nai fasal does not seem to understand that,” despairs Aas Mohammed. But this struggle for the Constitution, it is larger than the Delhi elections, he says.

Sitting on the steps of Jama Masjid at a protest against CAA-NRC, 34-year-old Nida (who doesn’t want to share her last name), says: “Matia Mahal will see a sweep for jhadoo — I say this with 98% confidence.”

AAP candidate Shoaib Iqbal has just hopped over from Congress and commands great clout in the area, having won every election (except the last) under various party banners. “My father is a kattar Congressi, but even he understands, why waste a vote this time,” she says.

In nearby Ballimaran, AAP MLA and minister Imran Hussain, a businessman who was an independent councillor before joining the party, is visibly popular. His office handles Aadhaar cards, ration cards, caste certificates and other paperwork, hospital referrals, and so on. “We have a daily footfall of 300-400 people here, and 10 staff members. Meanwhile, Congress candidate Haroon Yusuf (former minister and party heavyweight who had been elected five times from Ballimaran) does not even have an office in the neighbourhood,” claims AAP councillor Mohammed Sadiq.

He is dismissive about BJP’s polarisation campaign. “Delhi is the heart of India. People from all over the country, of all religions and castes and backgrounds live here. These issues of dharm and jati don’t impact Delhi, what matters are real issues”. AAP volunteers claim to have constructed 100 borewells, and replaced 80% of the sewerage network in the area. There is a mohalla clinic close by, and three schools are being built. “The borewell work began with Haroon Yusuf, he has also worked. But with him, ek- zamana-tha wali baat ho gayi — I think he should have sat out this election,” says Mohammed Asif, who runs a spectacles shop in Ballimaran.

He makes a clear distinction between the Lok Sabha election, where “bigger internal and international issues matter”, and this one, which is about service delivery, about gullies and sewers, water and electricity, schooling and health. AAP has worked hard on all fronts, he says. Fees have been waived for minority students who can produce an income certificate, says Nazma Bari, an ad hoc teacher in a municipal school in Matia Mahal.

For many voters, it is not just a tactical choice between the Lok Sabha and Vidhan Sabha, there is a genuine satisfaction with AAP’s redistributive work. The slashing of electricity and water bills means more to the poor than abstract “development” work like flyover-construction that Sheila Dikshit used to talk up, they say. “I used to pay Rs 1,000-1,200 for electricity, Rs 2,500-3,000 sometimes for water. Now, it is nothing. I also got my GPS SIM free,” says Zamir Ahmed, an auto driver.

Meanwhile, an e-rickshaw driver, Mohammed Salim says that his 80-year-old mother sends duas for Arvind Kejriwal. “He won my heart when he spoke about getting corrupt officials suspended. He gets the pain of ordinary people.”

In northeast Delhi’s Seelampur, young Mohammed Javed, a tailor, says there is no contradiction between supporting Congress and AAP — “this time, it’s definitely Kejriwal for many of us”. His friend, Amit Verma, is an ardent BJP supporter, and they rag each other mercilessly over politics. “He’s a worm, but I love him,” says Javed. “We don’t fight, only stupid people are made to fight over religion and politics,” says Verma.

Download The Times of India News App for Latest Elections News.

more from times of india news

Get the app