Janardhan Patil (right) of Star Agriwarehousing at a warehouse. (Express Photo by Parthasarathi Biswas)

Janardhan Patil (right) of Star Agriwarehousing at a warehouse. (Express Photo by Parthasarathi Biswas)

Yogesh Thorat isn’t impressed with Union Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman’s latest budget announcement of creating new agri-warehousing capacities or augmenting bank credit to farmers against negotiable warehouse receipts (NWR) that would be integrated with the pan-India electronic National Agriculture Market (eNAM) trading portal.

“In all such announcements, the devil is in the details,” declares the 32-year-old managing director of MAHA-FPC, an umbrella organisation of Farmer Producer Companies (FPC) in Maharashtra. In this case, the devil lies not just in building warehouses that adhere to the norms prescribed by the Warehousing Development and Regulation Authority (WDRA). There are at present as many as 1,744 warehouses registered by this authority under the Government of India’s Department of food and public distribution.

According to Thorat, while the accreditation process itself takes more than six months and lot of paper work, the country has no dearth of warehouses or even storage capacity per se. The real problem is in the NWRs issued by warehouse operators. Despite being so-called negotiable instruments — giving the bearers title to the underlying produce stored in the warehouses — few banks are willing to accept them.

Thorat speaks from personal experience. In 2014, MAHA-FPC sought to get its godown near Karjat in Maharashtra’s Ahmednagar district accredited. “After spending about

Rs one lakh, we realised that it wouldn’t solve any problem. Even if our warehouse were to get accreditation, the NWRs issued by it will not guarantee bank loans to the FPCs storing the produce of their farmer-members,” he points out. His cynicism is borne out by official statistics.

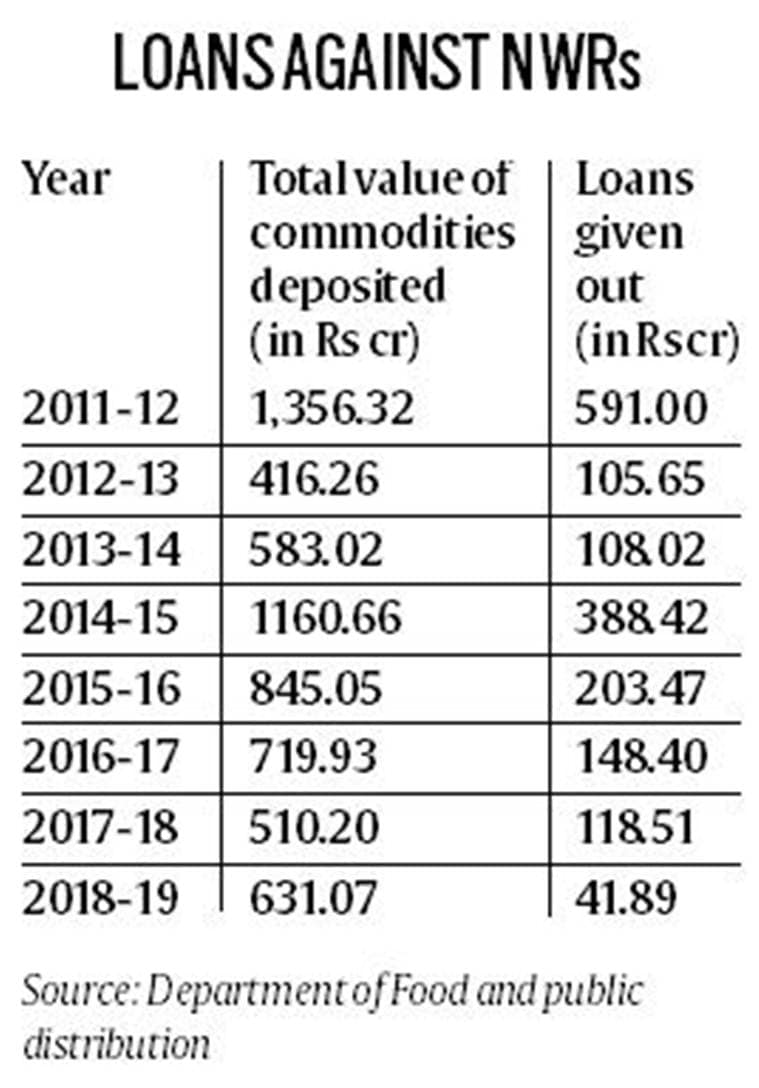

The Warehousing (Development and Regulation) Act was passed in 2007 during the term of the then United Progressive Alliance government. The WDRA was subsequently, on October 26, 2010, constituted as a regulator for warehouses in India. But as the accompanying table shows, the cumulative value of commodities deposited against NWRs over eight years, from 2011-12 to 2018-19, was just over Rs 6,200 crore. The total loans given out against these receipts stood even lower at about Rs 1,705 crore. Further, the value of NWRs issued as well as loans extended has actually fallen in the last few years. “The number of farmers borrowing from banks through this route won’t fill up even one room in my building,” remarks Thorat.

In her 2020-21 Budget speech, Sitharaman said that the Centre will provide viability gap funding for construction of WDRA-compliant warehouses on public-private-partnership mode at the block/taluka level, provided state governments make the required land available. The WDRA has, since September 2018, also launched issuance of electronic NWRs by registered warehouses. The depositors — traders or farmers — can now use e-NWRs to get loans against their underlying commodities from banks, while the lender’s claim or lien will be marked by a repository storing that data in electronic form. Sitharaman stated that the e-NWRs “will be integrated with e-Nam”. That would make them more secure, liquid and tradable, making it easier to obtain bank finance.

The basic idea of NWRs is appealing. Farmers typically sell their crop immediately after harvest. Since all of them bring almost their entire produce simultaneously to the market, it tends to depress prices. One way to prevent such sales — a result of farmers’ desperation for liquidity, necessary to pay off old crop loans and buy inputs for the next planting season — is to encourage farmers to stock their produce with warehouses. The latter would, then, issue NWRs, which farmers can use to obtain loans from banks. These could be up to, say, 70 per cent of the prevailing market value of the underlying stored commodities.

In practice, though, things haven’t quite worked that way. According to WDRA’s annual report for 2018-19, the country has an aggregate warehousing capacity of 162.71 million tonnes (mt), of which 77.68 mt are with private players and the rest with government or cooperative institutions. But barely a fourth of the accredited warehouses are currently issuing NWRs. Even the ones keeping their stocks with them are largely traders.

“The number of farmers storing their crop in warehouses and taking loans against NWRs would be insignificant. The bulk of commodities against which there are outstanding loans are held in warehouses owned or hired by Food Corporation of India, the Central and State Warehousing Corporations, and other state/cooperative agencies. Besides, there are traders undertaking delivery against futures contracts at platforms such as the National Commodities and Derivatives Exchange. They have to mandatorily transact through e-NWRs,” explains a Mumbai-based private warehouse operator.

At a 2,000-tonne capacity warehouse in Tanang village of Sangli district’s Miraj taluka, managed by Star Agriwarehousing and Collateral Management Ltd, its manager Janardhan Patil readily admits that few farmers are aware about e-NWRs or the scheme of availing pledge finance against them from banks. “Our customers are all traders,” states Patil. His company operates over 800 warehouses across 16 states with a total storage capacity of 1.5 mt. Only 50 out of these warehouses, however, are WDRA-accredited. And even that has been more in order to comply with the requirement of clients dealing in commodity futures exchanges.

MAHA-FPC, back in 2011-12, tried to raise loans against some 20 tonnes of moong (green gram) produce from its FPCs. “State Bank of India straightaway refused and we ultimately got a loan at 12% annual interest from RBL Bank. Very few banks feel confident to lend against NWRs,” claims Thorat. Nor does WDRA inspire much as a regulator, although it is supposed to be one on the lines of Securities and Exchange Board of India or Reserve bank of India. “Ours is probably the only industry that is calling for strengthening the regulator, but nothing’s being done,” says a warehouse operator tongue in cheek.

Jaya Prakash Guraja, chief operating officer of Star Agriwarehousing, one of the biggest industry players, is somewhat more optimistic. He believes that e-NWRs, which are more secure compared to paper-based NWRs, would add to the credibility of the warehouses issuing them. Since the information, including pertaining to the quality of underlying commodities, is stored in electronic form with repositories, they will enable greater transparency in trading of produce and also regulation by WDRA. “Being already-established collateral managers, banks find it easier to deal with us. They will feel even more so, once e-NWR issuances pick up,” he sums up.