In one of the most affecting scenes in The Sky Is Pink, a bereaved husband and wife take refuge in the solace of a restaurant washroom to discuss the aftermath of their daughter’s death. The husband offers moving to a different country as a solution. Astounded, the wife asks, “What will we do with her clothes? Her paintings?” This brief moment stands out in Shonali Bose’s film because, for once, it goes beyond what seems to be its central theme: embracing death rather than feeling betrayed by it. With this scene, it no longer remains preoccupied with the act of letting go but delves into how much to let go of, asks who decides it and — mainly — how to. It closely examines the different contours of grief and provides delicate portraits of mourning and melancholia

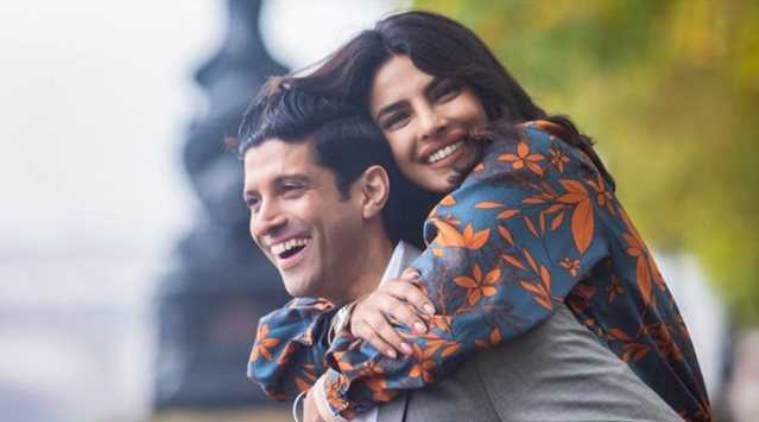

Based on a true story, it revolves around a couple — Aditi and Niren Chaudhary (Priyanka Chopra Jonas and Farhan Akhtar)– who lost their teenage daughter to complications rising out of congenital severe combined immunodeficiency. The tragedy had struck expectantly, making it more brutal. Aisha’s days were numbered from the outset. The struggle then was to prolong her stay; the fight was to make her survive than to just let her live.

For a film withholding such a premise, every act, every line threaten to throb with self-aware despair, the kind that tugs at your heartstrings knowing fully well that it is doing so. An emotional outburst is not just a natural reaction but an expected — often manipulated — one. Bose’s awareness of this is reflected in the way she chooses to tell a wider tale where a dying girl tells her story but does not put herself first. Where it is at once about her struggle to live and the constant wrestling of her parents with fate to evade an eventuality they know will befall. Departing from a narcissism that an apprehended death inadvertently enables the victim, Aisha’s caregivers — her parents and brother — are as much in the foreground as she is. The film constantly flits between different timelines and, by doing so, edges the most sombre moments with a carefree past; offsetting pathos with love. The Sky Is Pink then is also a heartwarming love story of a Chandni Chowk boy and a South Delhi girl, their midnight phone conversations, their accidental pregnancy, their shared jealousy and struggle and their eventual tragic triumph.

But this carefully thought-out approach which allows her not to overburden the narrative with pain also steers the film perilously close to the path it so deliberately seeks to avoid. The involvement of Aisha’s parents, her brother spreads the grief where it is not stretched thin and its impact is lessened but where it multiplies and outlives her death. Aisha’s death also becomes about her parents losing their daughter, a brother letting go of his confidante. It becomes about leaving and being left behind.

Theoretician and psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud explores the different ways of coming to terms with such losses in his 1917 essay Mourning and Melancholia and identifies these as the two responses. Although seemingly similar, he argues that they are, in fact, antithetical. Mourning is natural, he writes. It is time-bound and ultimately comes to an end. “Mourning as we know, however painful it may be, comes to a spontaneous end,” he notes in his 1916 essay, On Transience. Melancholia, on the other hand, is pathological. It is not a process but a continuous state of being where the loss is not recovered from. It is denied. To put it simply, he suggests that either one gets over the loss or gets subsumed by it. But his identification of mourning as a process also implies that when done together it becomes a sorrow comparing competition, lending the grief that follows a divisive quality.

Reema Kagti craftily underlines this dual ruinous quality of death in her 2012 film Talaash where a married couple struggle to grapple with the sudden loss of their son in their own ways and end up being embittered and estranged with and from each other. It is in this context that the scene mentioned at the beginning assumes such importance. Although it starts out as a comforting gesture, it pits the parents’ remorse against each other. Thus, when Aditi asks Niren what to do with Aisha’s clothes, she is actually asking, how can he leave those behind; how could he move ahead so soon leaving her behind. It is almost like Niren was done mourning and Aditi was not. Or maybe, as Freud writes, she was immersed in grief.

With all the limitations of the essay, chief among them being treating all losses uniformly and not accommodating for the various dimensions of grief, it is interesting to note how it has continued to serve as a common template in popular narratives, and, sometimes, even in life. In Talaash the couple find their way to each other after, what Freud would say, they are done mourning. In The Sky Is Pink, Bose does not let mourning sever ties by making us invested in their lives and love before the presence of Aisha, something Kagti does not do. Surjan (Aamir Khan) and Roshni (Rani Mukerji) were always parents. It seems only natural then that their son’s death robs their lives of meaning. Not only do we not know who they were before, they too seem to have forgotten. There is reconciliation at the end of both the films but they differ in texture. It is not acceptance that brings Aditi and Niren together but the shared promise they had extracted in youth to stay with each other come what may. They do not fall back on who they have become but on who they were.

One can read this as wish fulfillment, a cinematic rectification from the director whose own marriage collapsed after the death of her son. It can also be a cop out, a fervent wish to eke out a happy ending from aching adversity and thereby compromising on reality. But what she really does is finding a midway between the different stages of mourning — between mourning and melancholia if you will — and stopping at love. The ending affirms that contrary to what the theoretician had written mourning never ceases, that some losses stick to our feet and follow us around. But Bose embalms them with love. Their accidental encounter on the streets of London might as well be how they had first met. A lanky Chandni Chowk boy awkwardly smiling at a pretty South Delhi girl, amazed at his fate of finding her so. This time, they are older and more broken but still willing to give love another chance. Dipped in the folly of youth, they still believe that the sky can be of any colour they want. Even if it is pink.