Daad-o-tahseen ka ye shor hai kyun/Ham to khud se kalaam kar rahe hain (Why is there a crescendo of applause and praise/I’m merely talking to myself), wrote iconoclastic Pakistani poet Jaun Elia. A lot of poetry may spring from the poets’ conversations with the self, but when the bards gather for a mushaira, they have to find a meeting point with their variegated audience. At mushairas, poets hanker for daad with the intensity of a lover longing to hear from the beloved. Delhi will see such a gathering of poets vying for vigorous waah waahs from the audience on Friday, when the curtain rises on the 21st edition of Jashn-e-Bahar (Celebration of Spring), which has become an annual fixture on the city’s cultural calendar.

The mushaira mirrors the works of established as well contemporary practitioners of Urdu poetry and also serves as a microcosm of India’s syncretic cultural tradition and its diversity. Poets from Washington DC (Abdullah Abdullah), Houston (Nausha Asrar), Osaka (So Yamane), Doha (Aziz Nabeel) and Abu Dhabi (Syed Sarosh Asif), along with many from across India, will participate in the event organised by Jashn-e-Bahar trust, founded by Kamna Prasad. The Indian participants include veteran poet Wasim Barelvi, young poets like Iqbal Ashhar and Azhar Iqbal, and lyricist and poet Aalok Shrivastav, who will conduct the mushaira.

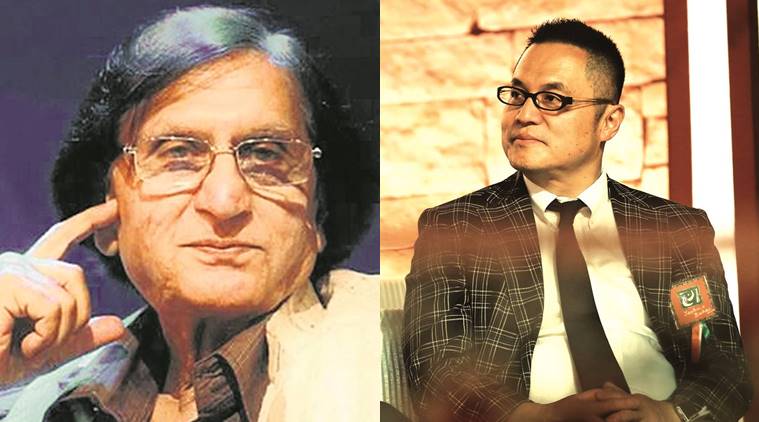

These poets, through their verses, will appeal to the audience’s core humanity and voice their joys and sorrows. Barelvi, 79, who has been regularly attending the event, says his poetry is the voice and realisation of his being that reflects in his words. “I have not written a single line for the heck of writing or by employing artifice. I never write poetry while sitting on a desk or a chair. I write poetry even while I am walking or talking. The harvest reaped thus reaches the masses or finds its way to journals and anthologies,” he says. In one of his shers (couplets) that he will recite at the mushaira, he talks about life’s ups and downs: “Jinhe aapas mein takrane se hi fursat nahin milti/unhin shakhon ke patte lahlahana bhool jaate hain (the branches that use all the time colliding with each other/it’s on them that the leaves forget to flourish).”

The mushaira, says Barelvi, is an institution of paband aazadi (bound freedom) and aazad pabandi (free bound), where you establish the order through self-assessment. He describes it as a consensus or synchronicity between saut-o-samaat (voice and the perception of sound). “It is a cultural act that harks back to, and is a shining example of, the age-old tradition of India,” he says.

Urdu, the language the mushaira aims to promote, is not just adab (literature), it is also about aadab (morals), says Prasad. She adds, “It’s not just a language, but also a culture that we’ve inherited.” Urdu has always taken everyone together, she says, adding that it’s the language of yakjahti (unity) and bhaichara (brotherhood). “Urdu ki bastiyan poori duniyan mein aabad ho gayin hain ab (The settlements of Urdu have mushroomed around the world),” she says. Barelvi echoes: “The public democracy (awami jamhooriat) of Urdu has reached all corners of the world.”

Prasad tries to invite poets writing ghazals as well as nazms to the mushaira, bringing together younger poets with the seniors, and voices from different regions. The poets, meanwhile, perhaps come here to seek solace in the camaraderie, connect with the audience and, most of all, in anticipation of daad. They thrive on it. Even Jaun Elia did.