As she leads us through the space, Rana Begum doesn’t refer to her works by any titles. Her third solo exhibition in Mumbai is eight days away and the empty walls and floors at the Jhaveri Contemporary art gallery in Colaba are slowly coming to life. There are four high tables; each features a dome, a smaller orange-shaped sphere, and cylindrical-shaped objects made from exquisitely striated marble in different colours — white, pine green, rust, and black. “These were inspired by floats used by fishermen in St Ives in Cornwall. They come in all sorts of shapes and they are so light. But I wanted to transform them into something heavy,” she says.

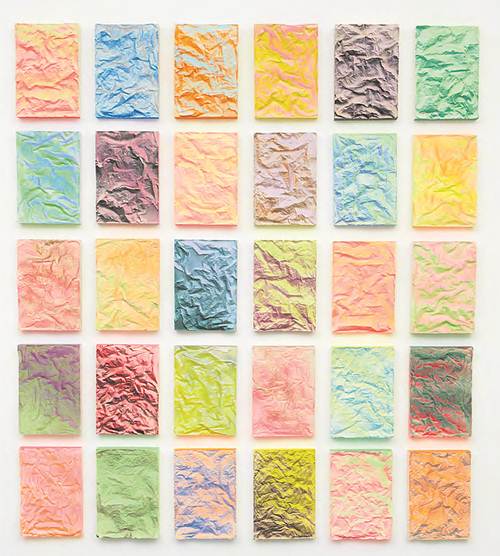

A wall near the window which looks out to the Gateway of India is filled with a grid of what, from a distance, looks like 30 pieces of crushed paper in bright hues but on closer inspection, is a mix of concrete and plaster, each one formed by hand to take on different shapes. We pause in front of a piece that has been made from spray paint on foil. Begum isn’t displeased to hear that the bright two-toned pieces recall a simpler time, that it reminds one of a candy wrapper, in the way the folds have retained their creases. “I enjoy listening to what the viewers make of the art. I feel uncomfortable to give it a name and to even have my name next to the artwork is unnecessary, because I don’t want to impose anything that can impact their interaction with it,” she says.

By doing so, the 44-year-old British artist, who was born in Sylhet, Bangladesh, and moved to the UK when she was eight, advocates the Barthesian argument that the author/artist’s work belongs to the reader/viewer to interpret, free from the creator’s meaning or intent. This makes Begum’s work rather transportive: it tugs at fragments of memories, giving the viewer an opportunity to place one leg in the past, and the other firmly in the present. This duality in her work stems from belonging to two distinct cultures, British and Bengali, as well as traversing the land that lies in between tradition and modernity.

For this exhibition, Begum has cast a fishing net wide across two walls and the floor — it’s been coated with different colours that bleed into each other quite harmoniously. “I bought the net when I was doing a residency in Istanbul but this work is based on my childhood memory of fishing in Bangladesh, where we’re surrounded by so much water. We used to go out in the boats, and look at how the light filtered through the nets, how it looked on the water. The work is very tactile and there’s movement in it because of the light. That’s what this show highlights: the relationship between surfaces, light and form, and the conversations we can have with them,” she says.

The interplay of light and surface has driven Begum’s work for a while now, in the form of coloured bars, folded stainless steel, powder-coated mesh and even drinking straws and UV lights. She traces her fascination with light, shapes and colours to her childhood in Bangladesh, when she read the Quran five times a day, sometimes in a mosque near her home. “It was constructed as a cube, with windows on either side and a water fountain at the centre — the light would just flood in, and I would simply stare at the sight for hours. For the longest time, I couldn’t connect those memories to my work, but once I did, my senses became more aware to everything around me,” she says.

Since she burst on to the global art scene a few years ago, Begum’s work has been described as ‘minimalist’; the term ‘optical illusion’ has been used as well. She maintains that there is no gimmickry at all. “As you interact with the work, it reveals itself to you, just as it has to me. I don’t begin a piece with a set idea, because I never know the way in which the light will interact with the surface,” she says. Where Begum exercises control is in the repetitive patterns that emerge in the works and in the exhibition as a whole. “I like repetition in my life, I like the routine and uniformity. It instills a sense of calm, and at the same time, I like to look for ways to create a chaos in the order,” she says.

Her two children, a 10-year-old son and seven-year-old daughter, love being in her studio. “Sometimes, I give them projects — take 10 photos a day, select one and tell me about why you’ve chosen it. And what they come up with is fascinating, I get to see the world through their eyes. That’s what I hope I can do with people who see my work too; when they step out, I hope they are more aware of their surroundings and all the ways in which relationships are formed with spaces,” says Begum.

The exhibition at Jhaveri Contemporary, Colaba, Mumbai, will be held from September 19 till November 2.