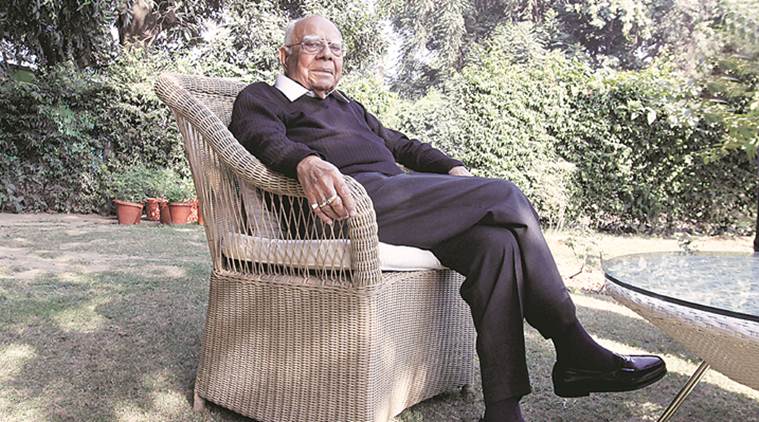

My dear, I don’t give a damn.’ When Margaret Mitchell made Rhett Butler say these words in Gone With the Wind, she had no idea that a formidable criminal lawyer in far away India would make this the anthem of his life. That man, born on September 14, 1923, was Ram Jethmalani.

Ram led a full life. An unconventional life. A life marked by acute ascent, immense popularity, paradoxes and controversies. Like most geniuses, he was a man of contradictions, but he was not contrived. He was constantly filtering new evidences, and then coming to new conclusions. He not only had the ring side view of some of the most significant socio-political events in Indian history, but has also contributed to some of them significantly. He saw India being born; any event, any person, any high profile case that makes up the collective memory of Indians, in some way featured Ram.

Ram packed in so much into his life that even attempting to fit his life into a few words is futile. He was a child prodigy. Within three months of entering his first school, Tekchand Pathshala, Ram was promoted to the third standard and not much later to the fifth standard. This made him the youngest, smallest boy in class. One day when Ram was bullied by a burly young man who lifted him by his collar, Ram struck the boy, leaving him confounded. He never caved in. In a moment he turned from the victim to the aggressor, a trait that marked much of his life.

A non-conformist, at every stage, Ram created a new normal — fighting his own case for admission at the bar at age 17, making a case for abolition of religion in his law college magazine, joyous libertine, crusader during the Emergency, observer of great piety to the rule of law; defending political radicals, reputed mob bosses, accused Godmen and alleged smugglers with equal ease and loyalty. A man with a hand in every pie, he was the famous protagonist of a case that peddle pushed the jury system out of India and acquired the halo of a Greek tragedy. But he was also the chief villain who came to the defence of Manu Sharma when all stood up in arms up against him.

He espoused various political ideologies and discarded them within the blink of an eye, always marching to the tune of his own inner drum. Ram was the force behind changing the definition of Hindutva and legitimising the ideologies of both the Shiv Sena and BJP within the constitutional framework. What’s more, he was open, unapologetic and irreverent about it. His single minded pursuit of what he believed in, his preternatural sense of right and wrong and his unrelenting doggedness stirred emotions, provoked moral judgments but never evoked ambivalence.

Ram’s achievements are enviable; some glorified and celebrated, and others understated. That Ram was a grand master of law, the undisputed champion of cross examination and rules of evidence is universally admired. Perhaps the least recognised is his contribution in setting up the National Law School of India University (NLS), Bangalore, India’s first five-year legal programme for students after intermediate. NLS was a culmination of Ram’s friendship with RK Hegde, Karnataka’s Chief Minister. Ram had represented Hegde’s son Bharat when the latter was accused in a corruption case and Hegde returned the favour by directing Bangalore University to allocate 14 acres of land for the law school on the outskirts of the city. He also ensured that the state of Karnataka parted with Rs 50,000,000 for the initial start up of the law school. It was a collective team of Ram, Upendra Baxi and Hegde who grandfathered the National University Act of 1986 which led to the NLS starting out as a full university founded by the state government. Ironically, when the NLS was inaugurated, Ram and his name were both missing. The school’s foundation stone was inscribed with the names of VR Reddy, the Chairman of the Bar Council at that time and Professor Madhav Menon. Ram remained an unsung and forgotten hero.

A few years down the line a young Kashmiri boy, who had failed the entrance for NLS, made his way to Ram, who ocured him an admission on unusual grounds. The boy reciprocated by acing his class. At the end of five years the boy secured a seat at Berkeley but was again struck by the weight of the expenses. This time too Ram showed up.

I had the good fortune of interacting with Ram Jethmalani on several occasions, not just for my book Courting Politics, in which I dedicate an entire chapter to him, but also on several other occasions. I remember asking him once how he would like to be remembered. His response was “ as a good teacher who could make a difference to the lives of the young.” And why not, till the very end Ram made every effort to share his legal genius with the young students across colleges in India. Even at 93, Ram flew every Friday evening after court to Pune to take a lecture at his most cherished Symbiosis College. The man who drank Cognac at home so he wouldn’t waste money on expensive liquor in hotels, chartered a plane at his own expense to take a lecture in Chandigarh because ,“the students were waiting to hear him.” The man who always courted attention and hype was vulnerable and generous to a fault when it came to legal education.

While his legal credentials are irrefutable, Ram’s political legacy is ambiguous. His political career was determined by his personal equations and several of his political actions were on a personal pique. He allowed personal disappointments to move him away from fixed positions, but he had the liver to take the consequences too, he was that sure of his moral radar and intellect. This is what made him invulnerable.

Ram was sui generis. I doubt there will be another quite like him. Sometimes the aggressor, sometimes the defender and at other both, Ram didn’t belong to anyone man, party, institution or idea. nd, when his best-laid plans seemed beyond his reach, he reminded himself of Ernest Hemmingway’s words from the poem, Invictus:

‘It matters not how strait the gate,

How charged with punishments the scroll,

I am the master of my fate:

I am the captain of my soul.

The “sinner with a clean conscience” has finally boarded onward from the “departure lounge”. Darlings, lets bow to his free spirit.

This article first appeared in the print edition on September 12, 2019 under the title “A Free Spirit”. Bansal, an IFS officer, is author of Courting Politics which profiles India’s top lawyer politicians. Views expressed are personal