In 2015, then chief justice of India T S Thakur asked Ram Jethmalani, already a nonagenarian then, when he planned to retire. “Why is My Lord asking when I will die,” he retorted, as the courtroom erupted in laughter.

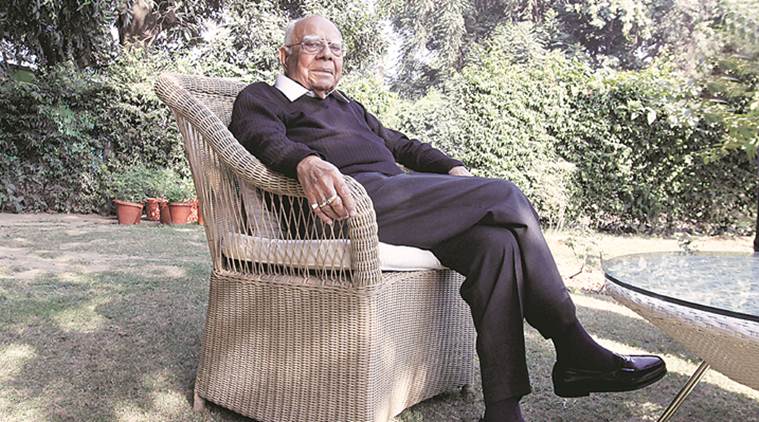

Veteran lawyer and former Union minister Ram Jethmalani, possibly a lawyer with the longest and perhaps most controversial career in the country, passed away Sunday morning. He was 95, and just two years into retirement from a practice going back to before Partition, during the course of which the non-conformist represented a long list of clients, from politicians accused of corruption and death row convicts to terror accused, accused in the assassinations of Indira and Rajiv Gandhi, and Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Home Minister Amit Shah in their legal battles. Jethmalani, who had not been keeping well for a few months, breathed his last at 7.45 am at his official residence on New Delhi’s Akbar Road, a few days before his 96th birthday on September 14. His last rites were held in the evening.

“In the passing away of Shri Ram Jethmalani Ji, India has lost an exceptional lawyer and iconic public figure who made rich contributions both in the Court and Parliament. He was witty, courageous and never shied away from boldly expressing himself on any subject,” Prime Minister Narendra Modi tweeted. Modi and Shah visited Jethmalani’s residence to pay their respects.

Born in Shikarpur (now in Pakistan) in 1923, Jethmalani was a brilliant student. He completed his matriculation by the age of 13 and began his career at 17 when he pleaded his own case against the minimum age rule for a lawyer to enrol at the bar, which was 21. Interestingly, he did not graduate in law but only obtained a two-year diploma — a condensed course introduced by Bombay University in 1939.

Opinion | He loved the law

Despite having spent six years at the bar in Sindh, Jethmalani had to qualify the Bombay bar once his family moved there after Partition. His first big break was the celebrated Nanavati trial, in which Jethmalani appeared for Prem Ahuja, the man killed by Naval Commander K M Nanavati. Ahuja’s sister roped in Jethmalani. Though he did not appear in the trial court, after Nanavati was let off by the jury and the judge referred the case to the Bombay High Court, Jethmalani assisted the public prosecutor for Maharashtra, Y V Chandrachud (later Chief Justice of India), secure a conviction for Nanavati.

During the Emergency, Jethmalani, as the chairman of the Bar Council of India, mobilised lawyers against the government. A group of around 300 lawyers, led by Nani Palkhivala and Soli Sorabjee, appeared before the Bombay High Court securing a stay on an arrest warrant issued against him.

Later, Jethmalani defended the men charged with assassinating Indira Gandhi, as well as the accused in the killing of Rajiv Gandhi seven years later. In fact, his on-off party BJP once expelled him for his decision to represent Mrs Gandhi’s killers, leading to acquittal of one of the accused given the death sentence, Balbir Singh.

Read | How Ram Jethmalani led the fight for people’s right to information

But in politics and his practice, Jethmalani remained a man of deep contradictions. While he wrote 10 caustic questions every day for then Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi on the front page of The Indian Express on the Bofors scandal for a few days, he also represented the Hinduja brothers, key accused in the same case, and secured an acquittal for them. When asked to respond, Rajiv had said he did not have to “respond to every dog that barks”. In response, Jethmalani said he was a “watchdog” and “watchdogs only bark at thieves”.

But, despite defending terror accused Afzal Guru and Khalistani terrorist Devinder Pal Bhullar, Jethmalani was in favour of retaining the death penalty law in terror and political violence-related cases.

Jethmalani’s decision to represent the Gujarat government was a turning point for the Modi-Shah duo in their legal battles. He defended Shah in the Sohrabuddin Sheikh alleged fake encounter case. Jethmalani argued that Justice Tarun Chatterjee, one of the two judges on the bench that ordered a CBI probe into the case, was under the scanner of the central agency in the multi-crore provident fund scam at that time. When Justices R M Lodha and Aftab Alam told Jethmalani that making allegations against judges could harm his reputation, he shot back in his trademark style, “I have no reputation to lose. If it is so, I don’t care.”

Also Read | From defending Advani to Asaram Bapu: A look at Ram Jethmalani’s notable cases

In 1977, Jethmalani first forayed into politics, defeating then law minister H R Gokhale from Bombay-North West constituency. In 1996, PM Atal Bihari Vajpayee appointed him the Union minister for Law and Justice. However, he resigned in 1999 following differences with then Attorney General of India Soli Sorabjee and then CJI A S Anand.

In 1998, he was given the portfolio of Urban Development and Planning and famously opened up the files in his ministry for public scrutiny. The move eventually contributed to the passing of the Freedom of Information Act in 2002, the predecessor of the Right to Information Act.

Jethmalani briefly floated own party, the Pavitra Hindustan Kazhagam, and even contested against Vajpayee from Lucknow in 2004, but lost. He later mended his relationship with the BJP by appearing for L K Advani in the Jain Hawala case. After he appeared for Shah in the encounter cases, he was rewarded with a Rajya Sabha seat by the party in 2010.

In just three years though, the relationship again soured and Jethmalani was expelled by the BJP for six years for “anti-party remarks”. He sued the party for damages and only “settled” the case after Shah formally expressed regret over his expulsion.

One of India’s highest paid lawyers, Jethmalani had since many years put up a board outside his house saying he would not be accepting any fresh cases and had upped his fee considerably to put off new clients. Still, lawyers, even seniors, would swarm already crowded courtrooms to witness Jethmalani argue whenever he did.

Such was his presence that during one hearing, Supreme Court judge U U Lalit, a criminal law expert himself, alternated between referring to the veteran as “Mr Jethmalani” and “Sir”.