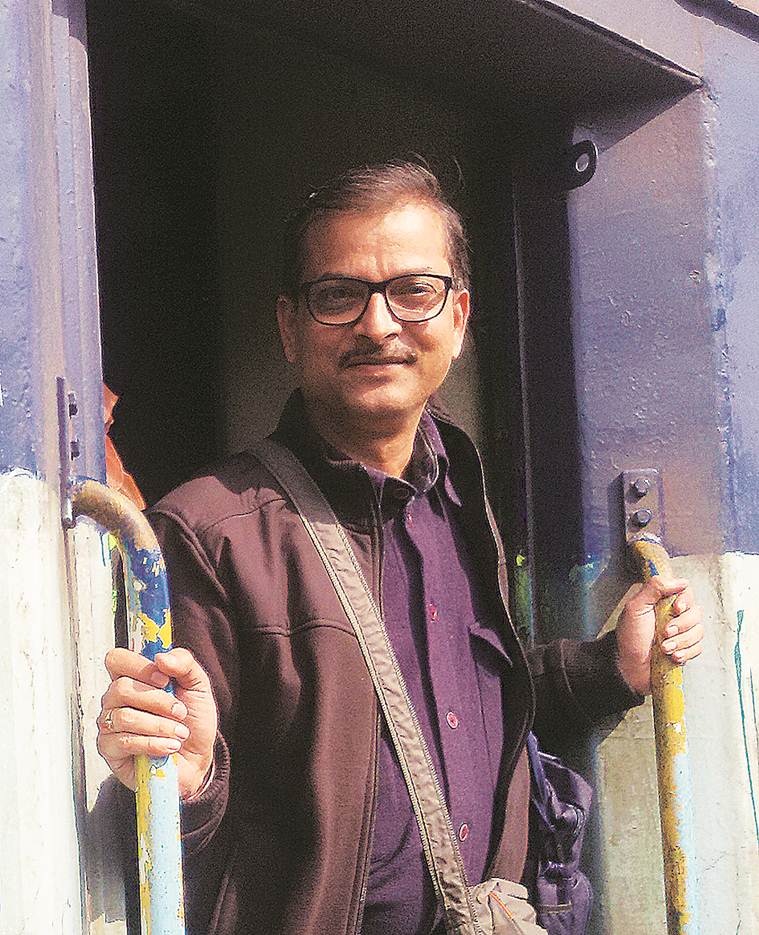

The demolition of a Guru Ravidas temple in Delhi on August 10, mandated by the Supreme Court, led to widespread protests in parts of Punjab and Haryana. In Delhi, a protest last month took a violent turn. Vehicles were burnt and broken: ninety-six men, including Bhim Army chief Chandrashekhar Azad, were arrested on charges of rioting. Santosh K. Singh, associate professor of sociology at Ambedkar University Delhi, who has spent a decade studying the 16th century poet-saint of the Bhakti movement, explains why the Ravidassia community is fighting this battle of pride. Excerpts:

Tell us about the assertion of Ravidassia identity in the 21st century.

To understand the recent protest in Delhi, one has to visit Varanasi and Vienna through Jalandhar. I am not kidding. In today’s world, a heavily networked society is mediated by technology. To understand the phenomenon, one has to understand the history of 19th-20th century Punjab, especially the Doaba region, where the consolidation of the Ravidassia identity began, and picked up momentum in the 1920s. Things, however, gradually changed in recent decades, when a more aggressive articulation of Ravidassia identity began under the leadership of some of the deras (temples) of Punjab.

Sant Ravidas was born in a Chamar community, one of the untouchable castes, in UP’s Varanasi in the 15th-16th century. The sant belonged to the nirgun tradition and advocated for “Begumpura”, a world without sorrow and inequality. He was enormously popular in his time because of his gentle yet profound egalitarian philosophy. In Punjab’s Doaba, which in the colonial times was the centre of the leather and boot industry, there is a large concentration of the Ravidassia. A large number of people who made a living out of this leather-based work migrated to many parts of Europe, Canada and the US.

One must recognise that the people who make Sant Ravidas so visible and relevant today are not necessarily the Ravidassia of UP or MP. It’s the rich, numerous and prosperous Ravidassia of the Doaba region and their diasporic segment who used its — what I call — rich ‘diasporic dividend’ to not just rework this identity but network globally. A large number of the early flush of migrants from Doaba were those who earned a respectable position in alien lands through sheer industriousness. The second generation and the next are now into white-collar professions, and they are very rich and upwardly mobile.

After a few decades, they started coming back, and they are nostalgic, as diasporas always are, about their roots. Now that they have arrived in every sense of the term, they have come back to invest in Ravidassia deras. They are investing in Ravidas music; they are connected on social media. They say ‘Our guru was as enlightened as others, then why doesn’t he get his due? Is it because people still practise untouchability?’ Many of Guru Ravidas’s disciples were princesses, including the Rajput princess Mirabai. Such was his presence and acceptance at the time. ‘So, what happened later? We hear about Kabir but not Ravidas. Why?’ ask the younger Ravidassias.

Sant Ravidas was born in the 15th-16th century and the assertion of identity can be seen in the 20th century. What happened in the middle?

Many things, but most significantly, Sikhism emerged as the most formidable counterpoint to Hinduism’s orthodoxies and casteism. A large number of lower-caste communities joined Sikhism because it promised an equal, non-caste world. Later, caste hierarchies emerged in Sikhism, too. In Punjab today, you will find separate Dalit gurudwaras and Ravidassia gurudwaras. There are also separate marriage halls and cremation grounds.

Guru Granth Sahib, the holy book of the Sikhs, includes 40 shabds by Ravidas. The verses of many others, such as Kabir, Baba Farid and other contemporary sants, have been part of it. These sants are called bhagat, an equally respected word but considered below the guru. With a weakening of syncretic ethos of the past, there are newer questions being articulated, such as why are our sants not gurus?

In the 20th century, the Ravidassia community became more self-aware. The emergence of a Ravidassia dera, called Dera Sachkhand Ballan, in the 1920s in Ballan village, became a turning point. In the 1950s, Sant Sarwan Das of this dera sent his disciples to visit Banaras where Ravidas was born. The followers, under his instruction, found a tamarind tree near the Banaras Hindu University campus that he had a divine dream about. It’s here that the Guru Ravidas Janam Asthan temple is constructed in Seer Govardhanpur.

The Dera Sachkhand Ballan also came into prominence when one of its seers was killed in Vienna by radical groups in 2009. The death triggered the demand for a separate Ravidassia religion by the dera.

Why did Sant Ravidas not get his due?

India has traditionally been a caste-oriented society, it is an unequal society and maybe that’s why Ravidas didn’t get his due. When I meet Ravidassia families in Punjab, they take me to their prayer room — I see a photograph of Guru Nanak, a statue of Durga Maa, and a photo of Ravidas. They tell me, ‘We are equally respectful to everybody but we challenge you to find a photo of Ravidas at any other house.’ I have no reply to this. Our caste privilege decides what becomes mainstream and what is left on the periphery.

What is the community’s relevance in Delhi?

There is a strong Ravidassia community in Delhi. For instance, you will see tiny photos of Sant Ravidas placed on the pavements, on trees under whose shade the community work on leather. This is one end of the community, which then extends to many businesses and other high-profile jobs. Earlier, they were not so visible but now in a new networked society and through social media, the community is becoming conscious of itself, its history and traditions. This new world connects Punjab, Varanasi, Delhi and Vienna in a fraction of a second.

The recent congregation of the community in the national capital had a huge symbolic value. They want to stake their claim, be visible. If you look at Punjab demographically, almost 32 per cent of the population belongs to the Scheduled Caste — which is the highest in India — and within that the Ravidassia is the most dominant group. And, over the years, they have networked massively through Varanasi to forge a pan-Indian umbrella, and even a global Ravidassia identity.

From Bhim Army chief Chandrasekhar Azad to folk singer Ginni Mahi, the Ravidassia community is today represented by the young.

In UP, there’s a new paradigm of caste being imagined. Caste politics has gone for an overhaul. So, newer aspirants are trying to capture that space. Azad is one of them. He says, ‘We are proud of being from the Chamar community’. This is no different from what Mahi’s songs portray, where putt chamara di is pitted against putt jatta di. In Mahi’s videos, there are muscular men, fancy cars and open jeeps. The Jatts pride themselves on their masculinity and the videos by the Ravidassia community are an assertion of the same. Mahi represents that younger, no-holds-barred kind of Ravidassia identity. The salutation of the Ravidassia community is ‘Jo bole so nirbhai, Guru Ravidas ji ki Jai,’ meaning those who follow Ravidas are fearless.

I once travelled in the annual special train called ‘Begumpura Express’ that starts its journey from Jalandhar to Varanasi on Ravidas Jayanti and know it too well that the pilgrimage train journey is as much temporal as sacred. It unites not just a fellow Ravidassia from Saharanpur in UP to Saharsa in Bihar; it also connects them to their global fraternity in a big way.