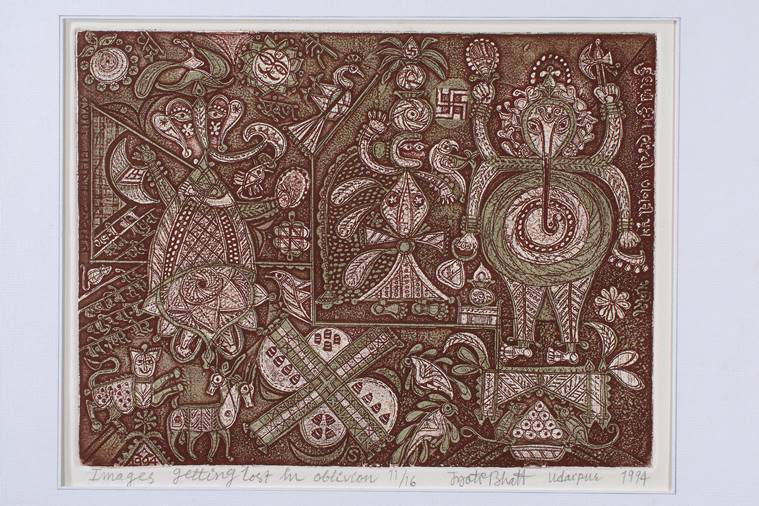

Best known for documenting the traditions and folk culture of rural India, Jyoti Bhatt is a pioneering photographer and printmaker. Awarded the Padma Shri for his contribution to art this year, the Vadodara-based artist’s works are in prestigious collections across the world, including the Tate Modern, London, and Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), New York City. The exhibition“Manushya aur Prakriti”, which opens at the Bihar Museum later this month, will bring together 82 intaglios and serigraphs, from 1958 to 2016. The 85-year-old talks about choosing a life in printmaking and using photography to document India’s folk culture.

Excerpts:

Could you share the origin of the Kalpavruksha series, which brings together man and nature?

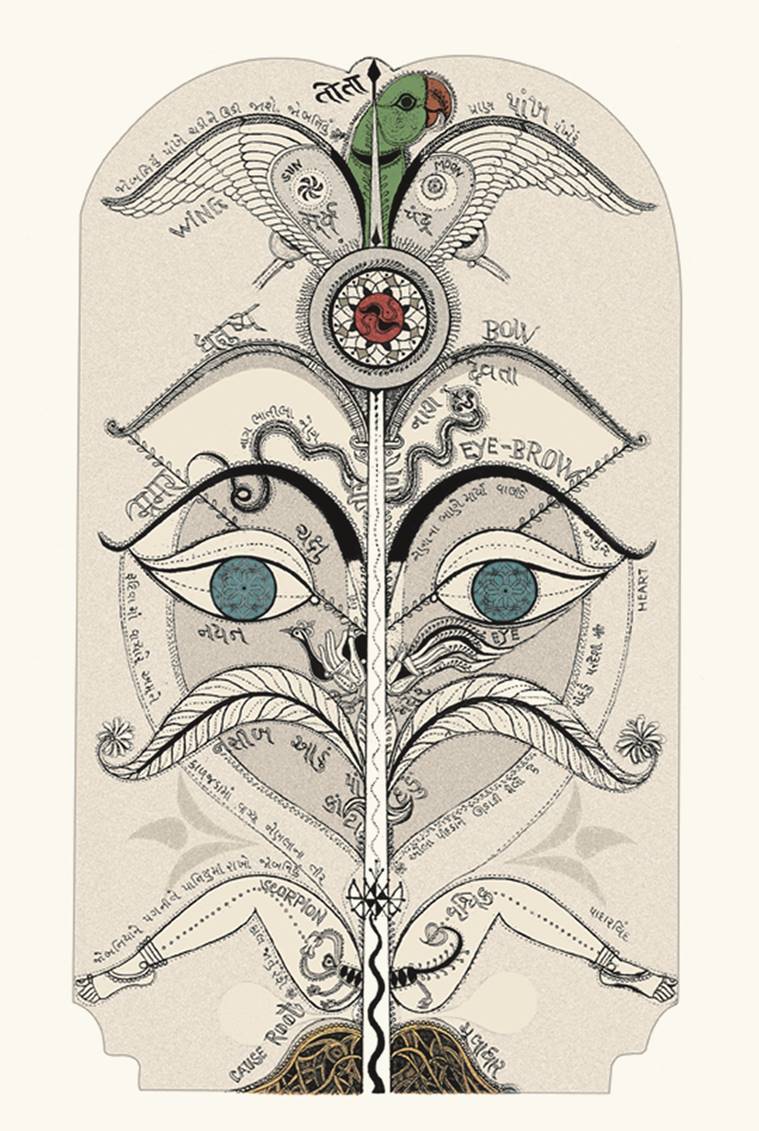

The concept of male and female elements is worded better in India as “Purush–Prakruti”. I had made one small print — about 5 x 5 inch — for showing certain techniques to the students of printmaking. It contained forms of a woman’s face, a mountain, sun and moon, snake and so on. I titled it Meru. The second plate, Purush-Prakruti, was 10 x 10 inches. Usually I title my works just before they go for an exhibition. I must have been reading a poet describing a woman’s eyebrows as dhanushya (bow), when I made the 1972 print with dhanushya-shaped eyes five times and then compared that shape to the wings of parrots, leaves of trees and so on. The vertically arranged form would have reminded me of the mythical tree.

What attracted you to printmaking? You did your first etching when you were in Italy in 1961 and then started experimenting with intaglio in 1964, when you were at the Pratt Institute in New York.

Through prints, my work could reach a larger audience. In addition, during the printing process, I could make various “avatars” (versions) of the same image, without losing the core elements of the images.

How did you encourage other artists at MS University, Baroda, to take up printmaking.

MSU had printmaking as one of the optional subjects from the beginning (1950). Initially, woodcut was the only subject taught and in the second year NB Joglekar introduced lithography. He looked after the technical aspects and professors NS Bendre and KG Subramanyan taught the formal aspects. The department had purchased an etching press earlier but it could not be used as it was broken. It had been repaired when I came back from the US in 1966, and we started making etchings in the evening after teaching during the day. In 1968, the university introduced a postgraduate course in printmaking.

In the 1960s, you were asked to take photographs of Gujarati folk art for a seminar at Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan in Mumbai. Could you share your experience of travelling for the project?

In 1967, a seminar on Gujarati folklore was being held in Mumbai. Gulammohammed Sheikh and Bhupen Khakhar suggested the inclusion of visual culture, instead of just oral traditions. The organisers asked us to collect the necessary material. While travelling, I photographed the actual locations where such forms were placed. I realised that several native art traditions had either ended or were ignored. Whatever was still being done was disappearing slowly, so I continued to document them across India, till my health made it difficult for me to do so.

Did your interest in photography begin with the 1957 exhibition curated by American photographer Edward Steichen and brought to Ahmedabad by MoMA?

People used camera as a machine for making art immediately after its invention was made public in 1939. However, soon the documentary aspect of photography began to dominate, so much so that Alfred Stieglitz, Edward Steichen and the photo-secessionists (who wanted to move away from the photographic idea of accurately representing the world) had to struggle to re-establish photography as an art form. The exhibition which Steichen curated for MoMA convinced me about the communicative power of photography, which inspired me to use the camera.

In 1969, you organised the exhibition ‘Painters with a Camera’ — including works by Sheikh, Jeram Patel among others — in Bombay. Do you think photography has got its due as a medium of art?

The exhibition was a group effort. I don’t think it changed the attitude of photographers and people then. It’s only recently that researchers such as Diva Gujral have started taking interest in how painters (Krishen Khanna and us) have used the camera.

You were 12 when you made one of your earliest paintings, Chheta R’ejo, depicting an ‘untouchable’ man. What prompted you to make that? Could you also tell us a bit about your childhood in Bhavnagar.

At 12, one is mature enough to understand and react to things happening in one’s surrounding. This painting was shown at an exhibition in my school in Bhavnagar. Some parents were unhappy and complained to my art teacher, Jagu Bhai Shah, that the theme depicted was “too dirty”. Fortunately, he convinced them that artists must have freedom of expression. He treated us kids as established artists and as his younger friends. This was in 1946, when Gandhiji was understood better than today. I was fortunate that my schooling started at a bal mandir established by Gijubhai Badheka, who introduced the Montessori system in India.

You were among the first batch of students to study fine arts at MSU, Baroda. How was it to learn from teachers such as Sankho Chaudhuri and KG Subramanyan?

After school, I wanted to go to Santiniketan but when I heard about the new art college in Baroda, I decided to join it. It was like a continuation of my schooling. Like all other art teachers, Mani da (Subramanyan) often showed us ways of drawing or composing on paper. He often made drawings on the floor of the painting department that some of us would copy.

When analysing your linocut print Mother and Child, a jury member for the Fulbright Scholarship said that it seemed like a copy of Pablo Picasso’s work, even though it was actually based on a wall drawing you had seen in Saurashtra.

The 1961 linocut was made from a sketch that I had made in 1955. It depicted a cat with its kitten. In 1963, as part of the selection procedure for the scholarship, I was interviewed by a jury of specialists and one of them commented that the print was a copy of Picasso’s work. This irritated me a lot. I told him, ‘It is certainly a copy of a kind, but not of Picasso. Apart from a few minor but essential changes demanded by the print medium, the image I created is a fairly accurate reproduction of a line drawing made by an illiterate village woman or a girl on a wall of her hut near a seashore in Saurashtra. She belongs to a farming community and names such as Picasso, France, Africa, Cubism and so on do not have any meaning for her. I appreciate that you could see the similarity, but it is rather sad that you have no idea about so many of our own indigenous traditions, because you do not find them in the books you have on your shelves.’ I am grateful to the jury members that they were not offended by what I said and recommended me for the scholarship.

How was it to be an Indian art student in the US in the early ’60s? I read that you picked up a lot about the culture from MAD magazine, and that you learnt that the swastika has a different connotation in the west.

Since I was in New York City, I did not face any racial prejudices. My co-students and teachers never laughed or criticised my incorrect English. Before going to the US, I saw many Hollywood films and read MAD magazine, so that I did not face a culture shock like many other foreign students. I often use the swastika in my works because I feel it is one of the best designed symbols, but I realised that some of my friends who had Jewish connections were interpreting it differently, though I was never looked at as a Nazi or a Nazi supporter.

From 1964-66, you started depicting the self in your work. Could you talk about the role that the human face has played in your artwork since then?

The human face is the most photographed subject all over the world. However, I have used a profile of a human face in some of my works as a shortcut to say something about a human being or their situation.

In your later etchings we see several indigenous motifs — the peacock, parrot, scorpion, Indian gods and goddesses. What prompted you to use them?

The images in my work appear naturally and are reflections of what I have seen. While making my work I am aware that people other than me will also see it. I believe that viewers find it easier to connect with visual vocabulary. The motif of the scorpion comes from a Gujarati folk song that I sang as a child. I also liked the form of the scorpion and how it gets transformed in various tattoos and the zodiac. In my later works, I might have knowingly used this form as a symbol for libido.

We also see a lot of words and phrases in your works? Why do you feel the need to incorporate them?

Instead of giving information through titles and captions, I prefer to make the words part of the work itself. Written script forms are beautiful. I also hope that they work as a design element.

You were a teacher at MSU for several years. What is your opinion on art education in India, and on the restrictions in freedom of expression that we now hear about.

We don’t have any good art schools where art teaching is also taught. So, all art teachers are artists and when they become teachers, they follow the method of their teachers. Some are now studying in Western countries, so they use some of the teaching methods they experienced there. I retired in 1992 and don’t know much about the present teaching methods in art schools, but looking at the high standard of works of younger artists, the methods used today must be very good. The question of freedom of expression doesn’t apply only to visual artists and its pressure can be felt all around.