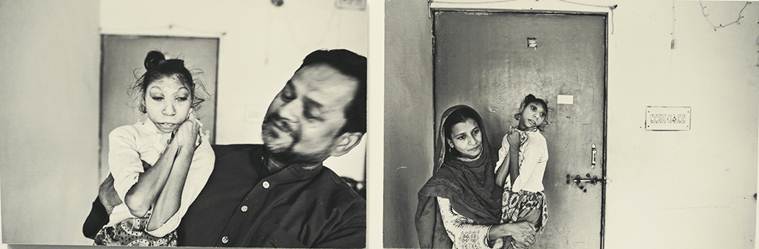

With her stiff body stretching up to an adult human’s arm length, and legs curled up all the time, Misba, 17, the daughter of a toy seller, is cradled in her teacher’s arm at her home, in a black-and-white photograph by Bindi Sheth. Suffering from microcephaly, wherein a child’s head is much smaller, leaving her with intellectual disability, the weight of her tiny body remained static for seven years, and she passed away six months ago. Three of her siblings suffer from the same condition and become part of the exhibition “Like Us”, which offers an intimate look into the lives of differently-abled children.

Nearly 35 photographs put the spotlight on the works of Prabhat Education Foundation, started by its founder Keshav Chatterjee in Ahmedabad, which serves children with special needs from low-income communities through counselling, therapy and learning activities. The organisation also works with the parents of these 3,000 children, who are mostly labourers, factory workers and helpers. Chatterjee says, “Misba’s mother would literally collapse and be tired all the time when taking care of her children. We helped her relax and also connected her to parents of other special children. We would also take visitors to her house to understand their community better and learn.”

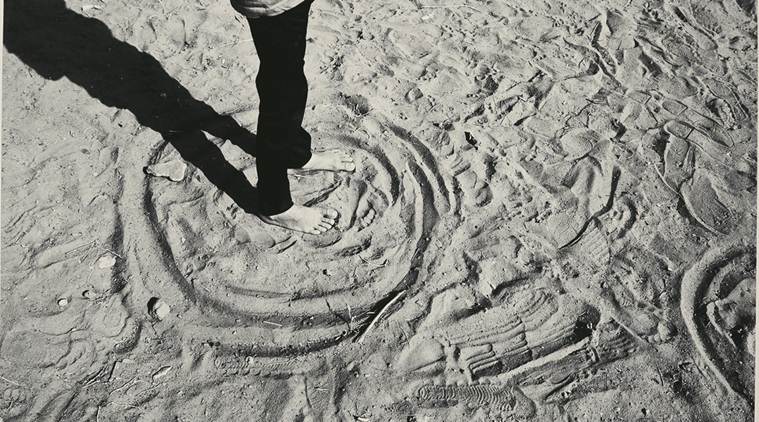

With nearly eight million children under the age of 19 living with disabilities in India, Sheth points out that the title of the show says it all. Adds the 50-year-old, “I have shot Prabhat’s children from close quarters, captured the faces of their parents and expressed what they are going through.” By photographing Hanif in a kurta, who suffers from a mental disorder, and offering a close-up of his hands engaged in cleaning the surface of a vehicle in a local garage, Sheth tells an inspirational story. The foundation agreed to pay the garage an amount of Rs 100 every month to employ him as a helping hand. The young boy is now employed there and gets Rs 200 every month.

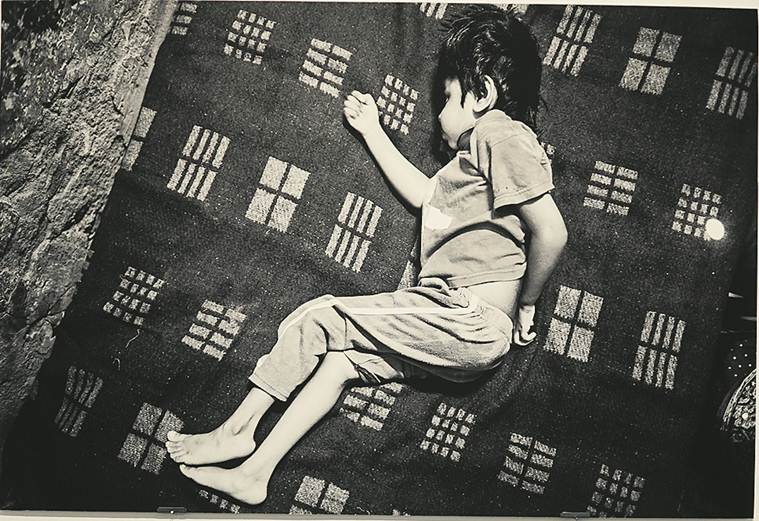

There’s 24-year-old Kangana, with behavioural issues, walking through the kitchen in one photograph. She mostly sits, starts throwing things around if she isn’t served what she asks for, but ensures she doesn’t get hurt in the process. A bunch of boys with mental disorders, standing beside a wall in a frame, bring out the case in point of how many of them if they venture out of their house, will never be able to find their way back home. Chatterjee says, “Many a time when someone is blind, it is easily visible, and people would sympathise with them. But these children do not have that advantage.” By photographing children with autism, Down syndrome and cerebral palsy, the aim of the show, says Sheth, is to tell the parents and their community that they are not alone.

Chatterjee recalls how he once went looking for one of his students, Samira, in her colony in 2008 and nobody had an inkling about her until someone referred to her as ‘that mad girl?’. Langda and hakla are other nicknames given to some of these children. He says, “Samira made us rethink about the environment at their homes. Once these children return from the centre, their own siblings didn’t play with them. Our children kept looking through the window and watched them play. That’s when we realised we have to work at the ground level and started decentralising and going to people’s house to educate so that the community can see what we do.”

The exhibition is on at India International Centre, Delhi, till August 11