International film studios are going all out to localise their films for the Indian audience. They are not only releasing films in different languages like Hindi, Tamil, Telugu and Malayalam, but are also pulling in big stars from the Indian film industry to voice the lead characters of their films.

This July, Disney India took localisation to a new level with its initiative to sign Shah Rukh Khan and son Aryan Khan to dub for Mufasa and Simba, respectively, in the remake of The Lion King. To pen the dialogues in Hindi, they pulled in screenwriter and lyricist Mayur Puri, who has been bringing alive Disney and Marvel dramas for Indian fans for a while now.

We recently interacted with Puri to understand the process of writing the dialogues for the Hindi version of an international film. Puri said, for him, it is important “to translate emotions and feelings of a character and not the exact words.”

1. How do you begin the process of writing the Hindi dialogues for Hollywood dramas? Is it a literal translation?

It’s not a literal translation as they don’t work. To preserve the reality of the situation, we should be able to buy into the reality of a character. Whether that character is a car, a lion, a fish or even a human being, I should be able to buy into the reality of that character. If a character speaks about a train crossing in words like “lohpathgaamini suchika patika”, nobody will get it. So, the willing suspension of disbelief will only happen if we forget that this is a character and there is a screen. We have to make the audience believe that this is really happening. And if you want to do that, the most important thing is the language. People must hear what they hear in real life. So my Hindi adaptations are purely governed by the thought that I have to translate emotions and feelings of the character and not the exact words.

2. So what special care is required while you are writing the dialogues?

There are two aspects to it. One, the art or the feel of it and the other aspect is the craft of it or the science of it. There’s a lot of math involved. I don’t want to give you a lecture on prosody and how we do it. But it isn’t complicated. You have got to understand the syllables, where your lips close and where they don’t while speaking. Like how the human body behaves when we are speaking and how your jaw behaves. We have to consider that to achieve a lip-sync or a match which is as close to the original as possible. But this is one part of the job.

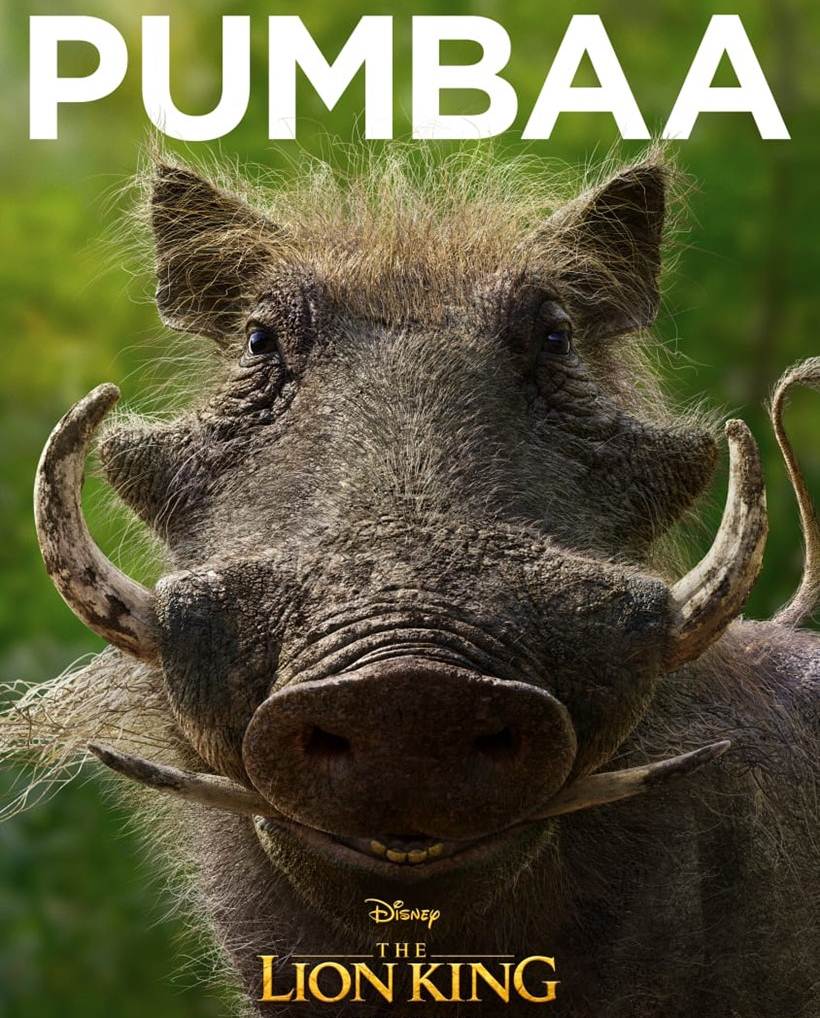

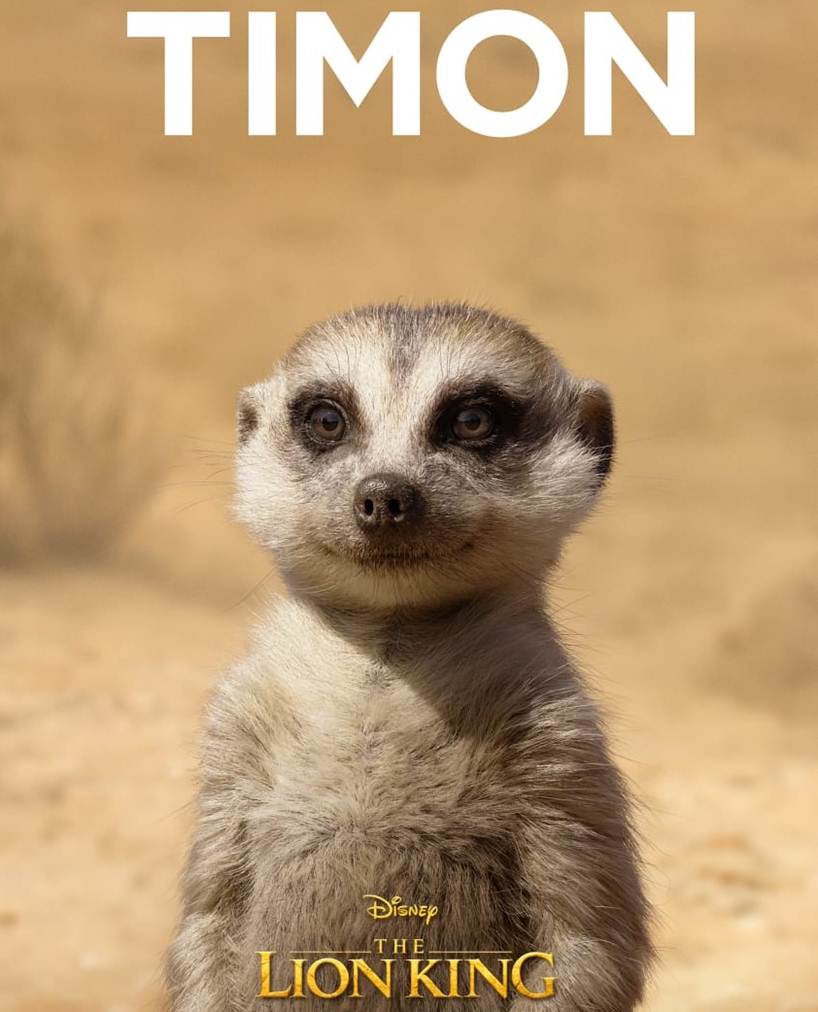

The other part of the job is to understand the context. Language is all about context. In the hands of a good writer even a ‘sorry’ and a ‘thank you’ can become a memorable thing. Like Sooraj (Barjatya) ji used “dosti ka ek usool hai madam, no sorry, no thank you.” So it’s all about the context. Take for example, when Pumba and Timon say, “Leave it, we are outcasts,” if I translate it into “Hum logg jaati ke bahar hain,” it doesn’t make any sense. So, when I changed it to, “Hum logg faaltu hai re,” it means nobody cares for us and you are bound to feel bad for them. So, you have to take care of context, relatability, emotion and syllables. It looks simple but it is not.

3. Do you try and give different dialects to different characters?

I try to adapt the dialects according to the realities of our society. If you notice, Pumba and Timon are street smarts, they speak typical Mumbaiya language. Where they live, there are people from different families and different places. So, you have to find a point where all these people can come together and talk in common lingo. This is just like Mumbai. People from all over the country come to the city and pick up its local language. We all understand that language. That’s why not just Timon and Pumba, all those small creatures speak in the same lingo.

Finding a language for the Hyenas was tricky. It had to be Hindi but I wanted them to have their own identity, culture and language, probably of the people who have lived in difficult circumstances but have become threatening as well. So, earlier this year I visited Jharkhand and Ranchi. I spoke with a lot of people there and saw open coal fields and mines. There I felt the correct placement for the hyenas. Now, the language that is spoken in Jharkhand, when it is written, it is very respectful. But when it is spoken, there’s a certain robustness that comes with it.

4. Before you start writing dialogues, do you get any briefs from the original screenwriters?

Disney has a creative team and they work with me on every draft. We sit together and take decisions. There is a docket we follow like a Bible. It gives details for every character and dialogue, why it’s spoken and what’s the context. Like Mufasa is very honest and he’s a very just king, so that little bit of ideation we have. As we progressively do our Hindi draft, we also ask them if they can give us some options for places where we get stuck.

5. For Lion King, did you keep Shah Rukh Khan in mind while writing the dialogues?

By the time Shah Rukh sir joined, the Hindi script was already locked in. Moreover, he is a very consummate professional. He respects the written word and he will do exactly what is written on the script. I have worked with him in other films (Om Shanti Om and Happy New Year) as well. You might have to change a word here and there for other actors but for him, you never have to change anything.

6. Which has been the most challenging project?

The most challenging one for me was probably Moana. It was for two reasons. One, it had nine songs and I had to write all of them and second, it was a film about sea fairies. Indian audience is not a sea fairy audience because the Hindi heartland comes from the riverside, and not oceans. We have a lot of terminology for the river, plants, trees, flora and fauna, but we don’t have words for sea fairies. So that was a nightmare.

7. “Picture Abhi Baaki Hai mere dost”, “ek chutki sindoor” have become iconic dialogues and will be remembered by generations. Do you think this is the biggest recognition for a writer?

Well, the biggest recognition is people talking about your work, recognising your face and them thronging you for an autograph. That doesn’t happen in a writer’s life so much. There’s no substitute for actual fame. But yes, it’s a good thought to fool yourself that ‘oh people remember you because of your dialogue.’ The truth is it will always be the actors who will be recognised. I am a realist and not one of those who live in ivory towers. There was a time when writers were like rockstars. Even actors would be afraid of them. They had so much power, dignity and grace. But after Salim-Javed, I don’t think we have any poster boys of screenwriting. The shift has happened because the industry is star-driven now.