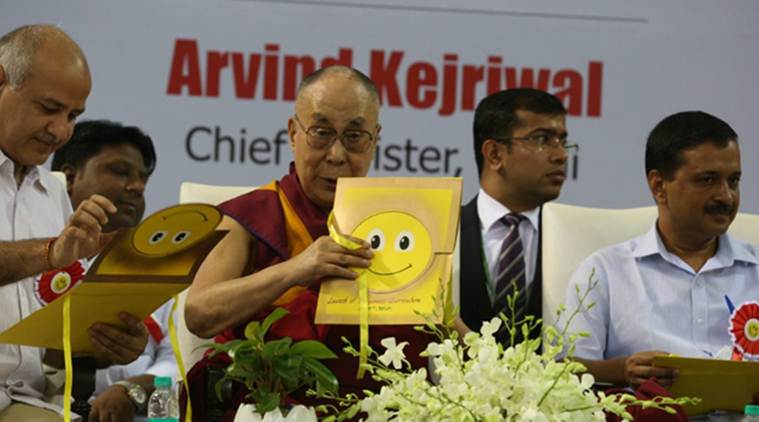

Recently, newspapers were inundated with full-page ads by the Delhi government declaring the success of their happiness curriculum, launched in MCD schools exactly a year ago. One of the most publicised (and novel) education initiatives by the Aam Aadmi Party (AAP), kids from Class II to VIII have begun their day with a 45-minute period pondering on what goes into building a satisfying life, along with lessons on compassion.

At the outset, this focus on lofty concepts like self-fulfilment and inner engineering seems crazy since it’s a well-known fact that government school students in India are floundering in a state of deep illiteracy. Study after study has shown that kids as old as 13 years of age can’t do basic division, or read. So, for politicians to be fixated on defining happiness while the fundamentals of arithmetic continue to elude these children, sounds preposterous. However, if one considers that in this day and age, education must be holistic — life isn’t just about chasing grades to further a career agenda — then, it’s only by prioritising mindfulness that we have any real hope of attaining some measure of contentment. Introducing this topic at the student level, irrespective of how well or badly it’s taught, kickstarts a thought process. If nothing else, a concerted effort to organise emotions and feelings is the first step towards clarity, which is the closest most of us will get to real happiness anyway.

For decades, the one aspiration the urban poor have held on to is to somehow drum up the funds to send their children to private schools. The state of neglect of Delhi’s MCD schools, often on prime real estate within the city, is a tragedy that successive governments have been unable to fix and the AAP team deserves recognition for their attempts to overhaul the system. By all accounts, teachers are actually showing up, PTM’s have become mandatory and the introduction of the CCTV, an excellent idea, enforces accountability for both students and the staff. It will take decades for the cultural emphasis on rote learning to start declining, and no doubt, the happiness idea is not only unlikely to achieve anything in the short term, but also has some serious flaws. Let’s face it: in a 55-student classroom what can one teacher — most likely a hardened skeptic — really say about happiness? If kids are coming from a background where parents are struggling to make ends meet, where every meal is precious and uncertain, and to a school where the coursework is always frustratingly beyond their intellectual reach, the conditions for satisfaction are not optimum. In such a situation, the very idea of teaching happiness seems cruel.

Perhaps the best to be hoped for from the happiness curriculum is that it serves as a cautionary tale to students; to be careful while choosing a path and know that even when one chooses wisely, things can go wrong. Hopefully, it provides some tools to deal with the inevitable disappointments that follow because, in our daily lives, we experience the evidence that nothing like universal justice exists — as you sow not shall you reap. Yet, students are fed this ludicrous myth that an elusive 90 per cent will magically solve all their problems. Is it any wonder they find it intensely confusing to discover that doing well is not all that it’s cut out to be. Our lives are made up of moments beautiful and otherwise, that follow each other in the continuum. Any curriculum that can help cultivate an attitude to cope, despite the circumstances, can only be a good thing.