Once upon a time when it was not uncommon to celebrate the opening of a book store with the coming together of the city’s cultural stalwarts, Shanta Gokhale played the titular role in the production of Snehalata Reddy’s Sita, to celebrate the setting up of a new outlet by publishing house Orient Longman in Bombay’s charming Ballard Estate. It was the year 1978, and, for the opening, Pearl Padamsee directed the radical work of Reddy — an artist and social activist who was imprisoned in the Bangalore Central Jail without trial during the Emergency and died on January 20, 1977 — that portrayed Ravana as superior to Rama. Satyadev Dubey, maverick theatre director, played the role of a dhobi, actor Victor Banerjee was Rama and Veenapani Chawla, who later founded Adishakti in Puducherry, was handling the show’s production for the first time.

At the rehearsals, Gokhale recalls struggling to follow Padamsee’s instructions. Once the show was over, Gokhale firmly traded her acting career for a seat among the audience, going on to become one of the country’s leading art critics and historians. From the beginning, Gokhale was clear about her critical parameters. “I deliberately did not write about the work I had not responded to positively. The space for art was shrinking. Why waste it on something I was not excited about?” says the writer and columnist, some of whose most important books include The Theatre of Veenapani Chawla — Theory, Practice, Performance (2014) and Satyadev Dubey: A Fifty-year Journey Through Theatre (2011) and The Scenes We Made — An Oral History of Experimental Theatre in Mumbai (2015); she edited the last two books.

But there is more to the bilingual writer than just a formidable body of critical work. She is also an award-winning novelist, a translator, a playwright, scriptwriter, teacher, and, even a public relations executive at a pharmaceutical company. “Shanta Gokhale resists definition…this may be one reason why even after I had marshalled all that was available of her writing…, I almost despaired of ever being able to put together a reader that would sum up her work in the world of words,” says Jerry Pinto in his introduction to The Engaged Observer: The Selected Writings of Shanta Gokhale (2016, Speaking Tiger).

For Sunil Shanbag, one of Mumbai’s prominent theatre personalities, Gokhale is “a renaissance person”. “She brings her varied interests and depth of knowledge to bear on her writing on history, culture, fiction, theatre, music, dance. In an age of narrow specialisations, she has a breadth which is of tremendous value in understanding the complex times we live in,” he says.

In One Foot on the Ground — A Life Told through the Body (Speaking Tiger), her recently-published autobiography, Gokhale, 79, writes why the idea of a memoir never appealed to her. “I came from a privileged family and there was no struggle that I had to overcome. However, Jerry has been nagging me to write a memoir,” says the 2015 Sangeet Natak Akademi Award-winner. The book traces the arc of her life over eight decades through the progress of her body, as it matures and then begins to wind down. It begins at the beginning — with her birth on August 13, 1939 when her mother, Indira Gokhale, was taken in a tonga to the Cottage Hospital, Dahanu.

Intertwined with the story of her body is her journey as an author and cultural chronicler. While reading American Buddhist monk Thanissaro Bhikkhu’s Contemplation of the Body in 2016, she found the idea of looking at the body “organ by organ, accepting it for what it was” appealing. “The idea of looking at the body and its life not as incidental to mine but central to it, excited me,” says Gokhale who wrote the book in eight months. What emerges is an account of a childhood in a progressive Marathi household in Mumbai’s Shivaji Park; her obsession with stories; years spent in England pursuing higher studies, the love of her Norwegian suitor Otto Tokvam, whom she gave up to return to India; falling for unsuitable men — twice; bringing up her children, actor Renuka Shahane and art critic-curator Girish Shahane, as a single parent; and surviving cancer. “Once the idea was lodged in my head, it didn’t take long to write. Unlike writing fiction, I was not inventing anything. It was a joy to write. I laugh at myself when I look back in life. There are so many silly mistakes that we have made,” she says.

The study room in Lalit Estate, located in Dadar West close to Shivaji Park, is filled with multiple bookshelves packed to the brim. It overlooks a semi-circular balcony with hanging plants. Gokhale’s parents made this their home when she was a year old. “While growing up, my favourite place used to be in front of the bookshelf. I used to pick up whichever book I liked from my father’s collection. Every month, my father used to come back from the Strand book store with an armful of books,” recalls Gokhale. Lalit Estate is one of the few old buildings in the neighbourhood to have escaped redevelopment so far. This is also the home where Gokhale had read out her first novel Rita Welinkar (1995) to poet Arun Kolatkar at one go on his insistence, breaking only to have the lunch she had prepared. Over the years, it has become a well-known address among the city’s culturati and literati who have come seeking the company of, in Pinto’s words, “Mumbai’s best-loved and most-easily-accessible sounding board”.

Sanjna Kapoor, co-founder of theatre and arts organisation, Junoon, says, “Shanta has always been a pillar of strength to me, someone I could call upon to respond to and help galvanise a half-baked idea. She is always happy to be in the background and play catalyst.”

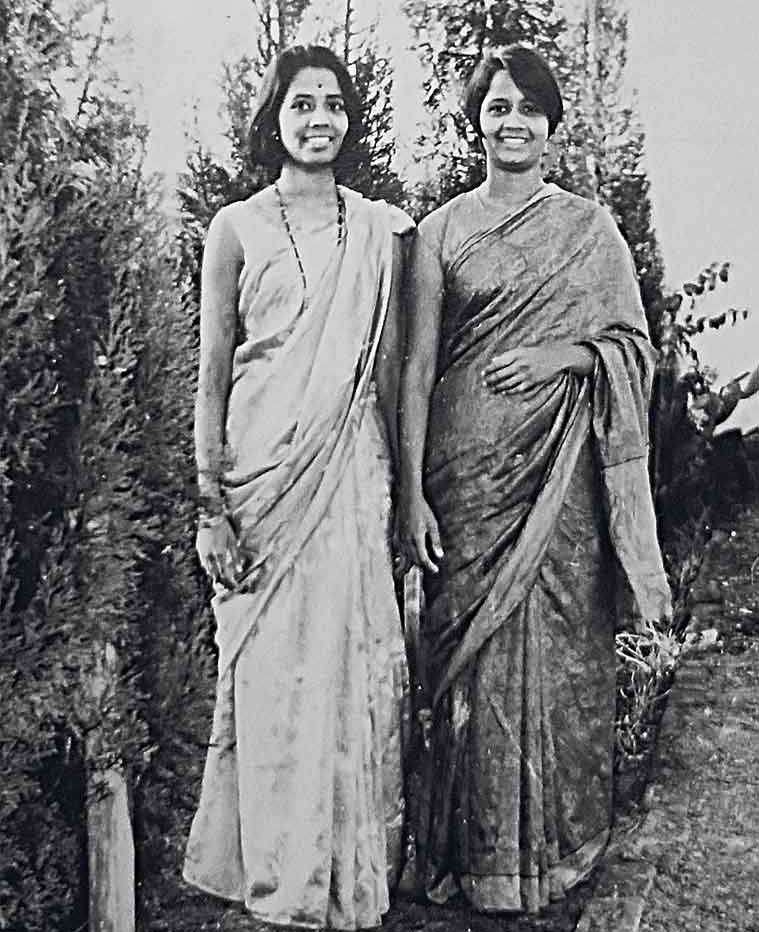

Much before Gokhale become a quiet force in the Mumbai culture scene, she started out as a writer. She was sent to England by her father GG Gokhale, a journalist with the Bennett and Coleman Group, along with her sister Nirmal, for higher studies. She has been writing compulsively since the age of 12. Her first published article was a letter about Rag Day, a festive fund-raiser in Bristol, which she wrote to her father. He showed the letter to a colleague, who decided to publish it. Following that, she contributed regularly to the paper.

Gokhale returned to India in 1962. But it was with a heavy heart. She had been in a relationship with Tokvam, whom she had met while she was in university at Bristol. He proposed after her graduation but Gokhale declined because the idea of staying away from India, or dividing her time between Norway and India — as Tokvam had suggested — was hard to accept. “It was very painful. He made a trip to ask me to reconsider. I knew I would be unhappy staying away from India. That would have made him unhappy. My parents would not have stopped me but secretly they wanted me to come back. There was a great feeling among people that the nation had to be built. People who had that capacity should do that in whatever small way possible,” she says.

During the years following her return from Bristol, however, she wrote irregularly, especially when she left Bombay after her marriage to Lieutenant-Cdr Vijay Kumar Mohan Shahane, whom she fell in love with because of his fondness for reading. By the time they were posted in Vishakhapatnam, Shahane had discovered rummy. “Rum and rummy were his companions at the club. The children were well-behaved and agreed to let me write when I wanted to.

Our understanding was that when I said I was not Aai (mother) but Shanta Gokhale, they were to entertain themselves and not bother me,” she writes. This is when she discovered her knack for translation. A letter from Dubey got her down to translate CT Khanolkar’s play Avadhya (1972), on the hypocrisies of middle-class morality.

Dubey wrote: “You are vegetating there. You’ve become a cow. Do some work. Translate the play that’s coming to you by separate post.” The play was hailed as “the first adult play” in Marathi, and condemned by the “cultural orthodoxy as obscene”. Dubey sent the translation to his friend Rajinder Paul in Delhi, editor of the theatre magazine Enact. “That was the first of my many translations that Enact was to publish,” says Gokhale, who has also translated Vijay Tendulkar’s Sakharam Binder (1972) and Mahesh Elkunchwar’s Vasanakand (1972).

Gokhale moved to Bombay in May 1974, soon after her mother sent her an advertisement for a junior lecturer’s post in the English department at HR College of Commerce. By then, the distance with her husband was growing. The marriage eventually ended in 1979. Gokhale joined the college and taught there for almost three years.

The nudge to apply for a journalist’s job came from poet Nissim Ezekiel. “You don’t really want to teach at a commerce college all your life, do you? Why don’t you trot over to Femina (women’s magazine)? They’re looking for a sub-editor,” he said. Earlier, Ezekiel had advised to her to give up poetry. The poet, impressed with her prose, had suggested she focus on that and also give writing in Marathi a thought. Gokhale had followed that advice and written short stories in Marathi for various publications. Years later, after struggling to find the right voice for Rita Welinkar, she would write it in Marathi, scrapping the four chapters that she had initially written in English.

Between her two stints as a full-time journalist — from 1977 to1979, and, from 1988 to 1993 — she joined Glaxo as a public relations executive and worked there for almost a decade. She started a theatre group for the employees and held 30-minute shows which could be performed during the 45-minute lunch break. Her first play Avinash (1982) was directed by Dubey. Later, she wrote plays such as Dip and Dop (1995), Rosemary for Remembrance (2012) and Shanbag-directed Sex, Morality and Censorship (2009). Her latest play is Menghaobi: The Fair One (2017) about Irom Sharmila.

In One Foot on the Ground, Gokhale talks about the need to have “a room of my own to be the person I was” echoing Virginia Woolf. In fact, the home page of her website shantagokhale.com, a gift from Girish, has Woolf’s famous lines from A Room of One’s Own (1929): “A woman must have money and a room of her own if she is to write fiction.” Gokhale’s wish was granted after the dissolution of her second marriage to filmmaker Arun Khopkar, whom she had married in December 1979 and divorced in 2006. In the chapter ‘Divorce and Marriage No 2’, Gokhale writes, “Rarely are women blessed with such blissful singlehood. The pleasure is not confined only to having my own space, my own work table and my own bookshelves. It extends to having my own cool bed… in which I can stretch my body any which way I like…The independence to be yourself, complete in yourself, is very heaven.” Her second novel Tya Varshi (2008) took shape in this heaven. Gokhale’s daughter Renuka recalls her complete absorption in her work. “Aai is a creative person first and a critic later. Both have given her a kind of integrity where a critic is also an excellent essay writer or translator or playwright,” she says.

In the last decade, Gokhale has come up with several translations and some original writings. She has also taken upon herself the onus of being an art historian. Shanbag says, “Shanta has been watching theatre and writing about it for the last 50-odd years, and that gives her a vantage position to be able to see patterns in the way the experimental theatre in the city evolved. She has engaged with so many of the key people who were part of this history. She has clarity as a writer. This kind of combination is rare and valuable.”

Gokhale dismisses any possibility of design in the way her life shaped up. “The different forms of writing I have done were my response to other people assuming I could do them and my willingness to give them a try. The translation happened because Dubey thought I could do it. Short fiction began because magazine editors felt I could do it. Scriptwriting began because Govind Nihalani asked me to do my first script. The only forms I attempted entirely for myself were plays and novels, both of which I wrote in Marathi because somehow they wouldn’t come out in English,” she says. Now that the memoir is out of the way, Gokhale rejects the idea of looking back at the life she has led. “If we’ve introspected as we’ve lived our life — and I do quite a bit of that — then we collect our answers along the way,” she says.

This article appeared in the print edition with the headline ‘A critic takes centrestage: What makes Shanta Gokhale a renaissance person’