Giorgio Piola's F1 technical analysis

Insight: How F1's first ground effect era revolutionised the sport

Formula 1’s 2021 car look set to bring a proper ‘ground effect’ concept back to the sport for the first time since it was banned at the end of 1982.

But while the idea of a full-length diffuser is different to the last time cars were designed like this, the aim is identical: produce the maximum amount of downforce possible through undercar aero.

Full coverage of F1 2021 plans:

Here, Giorgio Piola and Matt Somerfield look back at the history of ground effect in F1 by picking out the key cars and moments.

Click on the images to scroll through them...

Lotus 78 1977 detailed overview

Photo by: Giorgio Piola

The Lotus 78 was the first of what became termed ‘wing cars’. It utilised sliding skirts on the side of the car to enclose the inverted aerofoil-shape bodywork inside. Acting like one giant wing, the car would be sucked toward the ground, which radically increased downforce.

Lotus 79 1979 multiple view

Photo by: Giorgio Piola

Taking things a stage further with its 79, Lotus created huge Venturi tunnels within the sidepods and used the skirts to seal in the low pressure being created under the car.

Lotus 79 Ford of Mario Andretti

Photo by: LAT Images

The 79 made its race debut at Zolder in 1978 in the hands of Mario Andretti, and can be seen here in the pitlane alongside Ronnie Peterson’s 78.

Lotus 79 1978 ground effect comparison

Photo by: Giorgio Piola

This comparison of the two machines goes to show just how much more advanced the Venturi tunnels (left side of lower split diagram) were on the 79 than its predecessor (right).

The chassis of the Lotus 79 Ford, stripped of all bodywork

Photo by: LAT Images

Here’s a rare shot of the Lotus 79 chassis, showing just how simplistic cars of the era were when compared with their modern counterparts.

Mario Andretti, Lotus 79

Photo by: Rainer W. Schlegelmilch

The 79 was nicknamed ‘Black Beauty’. It scored six victories, and 15 podiums, won both the constructors’ and drivers’ championships, and locked in the future development path of Formula 1 for the next few years.

Brabham BT46B 1978 fan car detail view

Photo by: Giorgio Piola

The only other car to hold a candle to the Lotus 79 in 1978 was Brabham’s BT46B – or the ‘fan car’ as it’s more affectionately known. It’s an iconic machine as not only did it flirt with the letter of the law, but it only raced once before being withdrawn from competition by then team owner Bernie Ecclestone.

The Brabham BT46B Alfa Romeo fan car rear end

Photo by: LAT Images

Brabham’s chief designer, Gordon Murray, had noted Lotus’s ground effect concept but realised that creating Venturi tunnels with his team’s flat-12 engine would not work. In order to overcome this, he took inspiration from the Chaparral 2J ‘sucker car’, which used two fans to pull airflow from out under the body of the box-shaped car. Moveable aerodynamic devices were banned, but Murray had cleverly mounted the car’s radiators in such a way that it was argued the fans were there for cooling – but they also helped suck air out from underneath the car.

Lotus 79 and Lotus 80 comparison

Photo by: Giorgio Piola

The rest of the grid had been forced to sit up and take notice of the Lotus design to make their own ground effect cars. In order to retain its competitive advantage, Lotus set about taking an even bolder step forward. The Lotus 80 was supposed to be a full ground effect chassis, with skirts even placed in the nose region to capture the desired effect. However, the 80 was an unwieldy beast and suffered from a phenomenon known as 'porpoising', making the car particularly unstable in pitch and heave.

Arrows A2 1979

Photo by: Giorgio Piola

Arrows took a bold approach too with its A2, opting to tilt the Cosworth DFV engine in order that the winged section beneath the car was even more enlarged. While the car delivered significant downforce, it too suffered from serious aerodynamic instability and the team quickly ushered the A1 back into service.

Lotus 88 1981 aero overview

Photo by: Giorgio Piola

The Lotus 88 has become a footnote in a long list of designs that hold a mythical status in F1, largely because we are unable to assert how good it actually was. The ingenious double-chassis concept, which looked to reclaim some of the ground effect that had been lost when the FIA banned sliding skirts, was banned before it could be raced. The car performed exceptionally well during windtunnel testing, but it was actually a nightmare to drive as it produced rather unpredictable levels of downforce.

Ferrari F1-90 (641) 1990 floor

Photo by: Giorgio Piola

Speed and the forces acting on the cars and drivers spiralled to an all-time high during the ground effect era, often leading to catastrophic accidents. As such, the FIA took several measures throughout to try and reign in the teams but, in a final act, it ushered in new regulations for 1983 that saw the car outfitted with a flat bottom (seen here on the 1990 Ferrari) between the front and rear wheels with no skirts allowed at all.

Brabham BT52 1983

Photo by: Giorgio Piola

The FIA gave the teams very little notice of the ban ahead of the ‘83 season, and this led to Gordon Murray’s BT52B being both the most adapted car to line up on the grid in Brazil and arguably one of the sport’s most elegant designs.

McLaren MP4-14 1999 underside view

Photo by: Giorgio Piola

Flat-out speed and cornering forces began to rise steadily from there, as teams took artistic license with the regulations and began to incorporate the latest technology, which not only led to improved performance but also raised the stakes for the drivers, spectators and trackside personnel. The shadow cast over Imola in 1994, following the deaths of Roland Ratzenberger and Ayrton Senna, was finally enough for the sport to take action and introduce new regulations that required a step and reference plane which would deter designers from seeking performance through exaggerated ride heights.

Benetton B194 1994 underside plank view

Photo by: Giorgio Piola

From this point forward a plank would also have to be fitted to the underside of the car that would curtail the use of these extreme ride heights. Should the 10mm plank be worn by more than 1mm (10%) it would result in disqualification, a punishment that would befall Michael Schumacher, whose victory in Belgium 1994 was annulled. In Japan, the FIA allowed the installation of titanium skids, as Benetton had concluded that the damage had been caused by Schumacher leaping over the kerbs.

2021 F1 concept, front detail

Photo by: Giorgio Piola

Now, as Giorgio's 2021 concept shows, F1 will return to ground effect in future with venturi tunnels running beneath the sidepods.

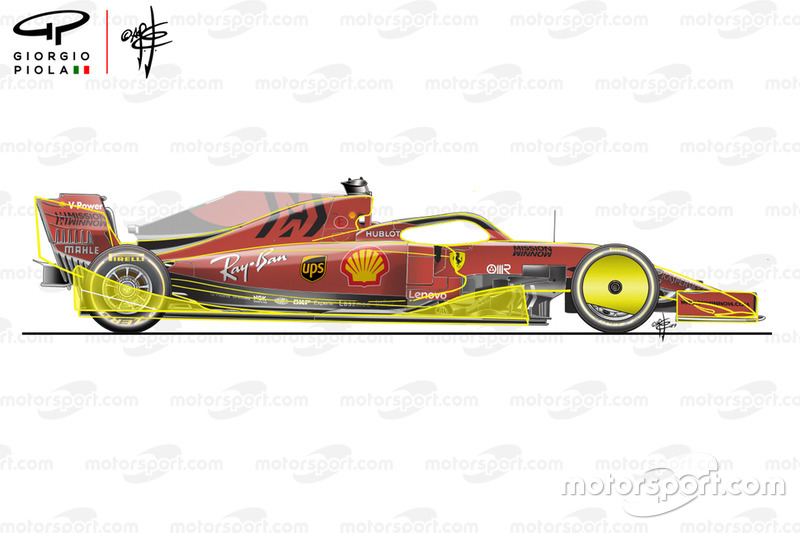

Ferrari SF90 2021-2019 car side comparison

Photo by: Giorgio Piola

The sidepod tunnels will end with a large diffuser behind the rear axle line.

About this article

| Series | Formula 1 |

| Author | Giorgio Piola |

breaking news