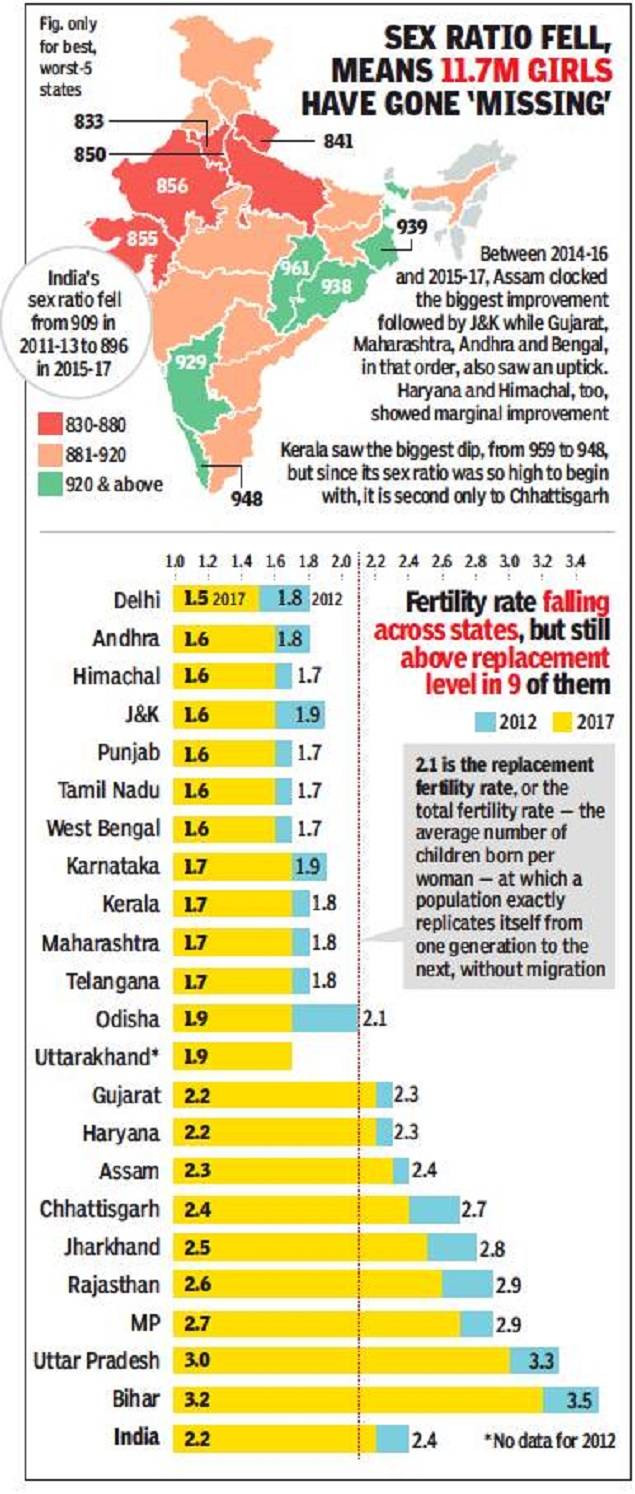

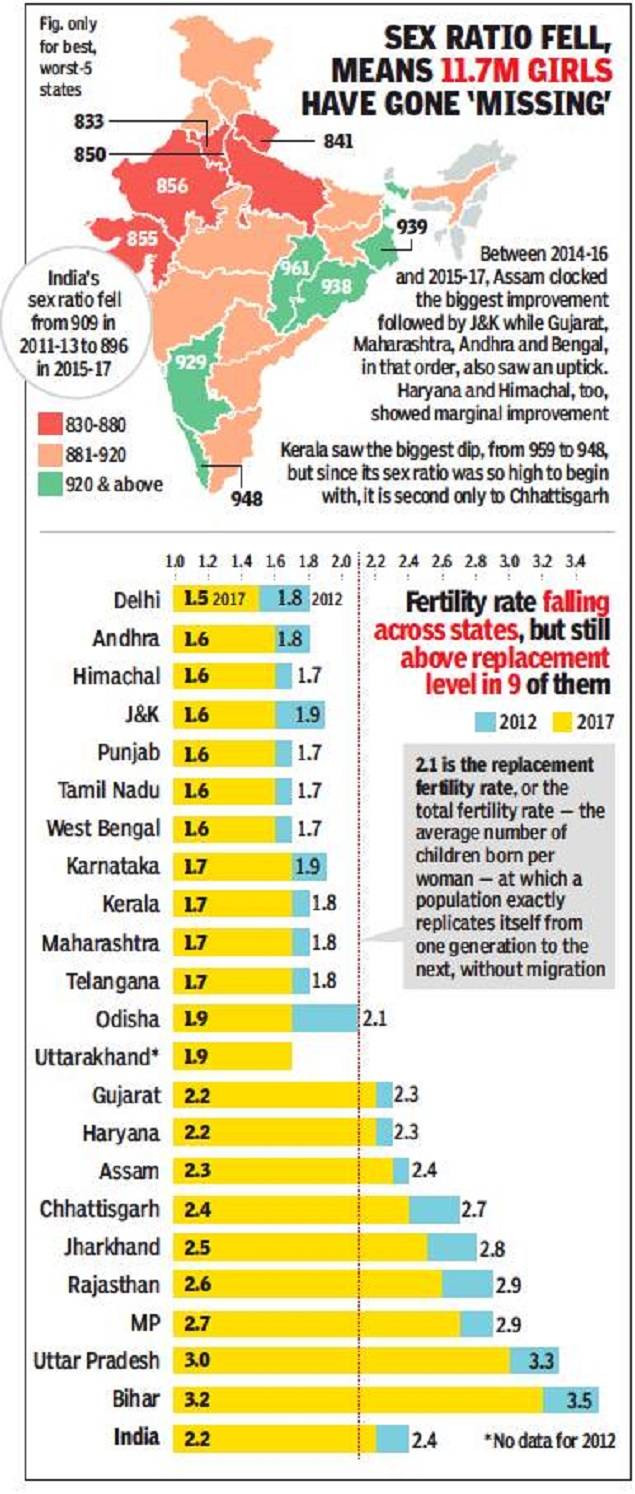

India’s sex ratio at birth (SRB) — the number of female babies born for every 1,000 male babies — fell to an all-time low of 896 in 2015-2017.

This would translate into approximately 117 lakh girls missing in the country in a span of three years. Five large states — Uttar Pradesh, Rajasthan, Bihar, Maharashtra and Gujarat — with poor sex ratios at birth account for about two thirds of these missing girls.

Uttar Pradesh alone accounts for about 34.5 lakh missing girls or about 30% of the total, followed by Rajasthan with 14 lakh, Bihar with about 11.6 lakh and Maharashtra and Gujarat, each with about 10 lakh girls missing in the three years.

While the sex ratio continues to decline despite government efforts, India’s total fertility rate — the number of kids likely to be born to a woman — which was stuck at 2.3 from 2013 onwards, fell to 2.2 in 2017, close to the replacement level fertility of 2.1.

Replacement fertility is the level at which a population can replace itself from one generation to the next without growing or declining and it is estimated at 2.1 children per woman. Below this level, the population starts shrinking. Nine states, including some of the least developed, have fertility levels higher than 2.1, though two of these, Gujarat and Haryana, are at 2.2. Only in Uttar Pradesh and Bihar are women on average likely to have three or more children.

Of 13 states with below replacement level fertility, Delhi has the lowest at 1.5. Barring Rajasthan, Bihar and Uttar Pradesh, urban populations of all states have less than replacement level fertility. In rural areas, MP, UP and Bihar have a fertility rate of three or more. India’s total fertility rate has fallen steadily from 3.2 in 1998 with the most dramatic improvement in the southern states where it fell from about 4 in the 1970s to the current level of 1.6 or 1.7.

The pressure to have smaller families in a society that prefers boys, along with access to sex determination methods and methods of getting rid of female babies could be leading to an alarmingly skewed sex ratio. Though some of the states with the worst SRB, such as Haryana, Gujarat and Punjab, have shown gradual improvement over the years, they are yet to regain the levels of the 1990s. Also, these are mostly states with smaller populations and fewer births. So, the improvement here is more than offset by declining SRB in populous states like Uttar Pradesh, Bihar and Madhya Pradesh with a huge number of births, leading to India’s overall SRB continuing to fall.

Moreover, many states that had earlier recorded high SRBs such as Kerala and Odisha have witnessed a steep decline. Kerala had an SRB of 948, second only to Chhattisgarh, but this has plummeted 26 points from 974 in 2012-14. In Odisha, the fall from 956 in 2011-13 to 929 by 2015-2017 is an even sharper 27 points.

This would translate into approximately 117 lakh girls missing in the country in a span of three years. Five large states — Uttar Pradesh, Rajasthan, Bihar, Maharashtra and Gujarat — with poor sex ratios at birth account for about two thirds of these missing girls.

Uttar Pradesh alone accounts for about 34.5 lakh missing girls or about 30% of the total, followed by Rajasthan with 14 lakh, Bihar with about 11.6 lakh and Maharashtra and Gujarat, each with about 10 lakh girls missing in the three years.

While the sex ratio continues to decline despite government efforts, India’s total fertility rate — the number of kids likely to be born to a woman — which was stuck at 2.3 from 2013 onwards, fell to 2.2 in 2017, close to the replacement level fertility of 2.1.

Replacement fertility is the level at which a population can replace itself from one generation to the next without growing or declining and it is estimated at 2.1 children per woman. Below this level, the population starts shrinking. Nine states, including some of the least developed, have fertility levels higher than 2.1, though two of these, Gujarat and Haryana, are at 2.2. Only in Uttar Pradesh and Bihar are women on average likely to have three or more children.

Of 13 states with below replacement level fertility, Delhi has the lowest at 1.5. Barring Rajasthan, Bihar and Uttar Pradesh, urban populations of all states have less than replacement level fertility. In rural areas, MP, UP and Bihar have a fertility rate of three or more. India’s total fertility rate has fallen steadily from 3.2 in 1998 with the most dramatic improvement in the southern states where it fell from about 4 in the 1970s to the current level of 1.6 or 1.7.

The pressure to have smaller families in a society that prefers boys, along with access to sex determination methods and methods of getting rid of female babies could be leading to an alarmingly skewed sex ratio. Though some of the states with the worst SRB, such as Haryana, Gujarat and Punjab, have shown gradual improvement over the years, they are yet to regain the levels of the 1990s. Also, these are mostly states with smaller populations and fewer births. So, the improvement here is more than offset by declining SRB in populous states like Uttar Pradesh, Bihar and Madhya Pradesh with a huge number of births, leading to India’s overall SRB continuing to fall.

Moreover, many states that had earlier recorded high SRBs such as Kerala and Odisha have witnessed a steep decline. Kerala had an SRB of 948, second only to Chhattisgarh, but this has plummeted 26 points from 974 in 2012-14. In Odisha, the fall from 956 in 2011-13 to 929 by 2015-2017 is an even sharper 27 points.

Download The Times of India News App for Latest India News.

more from times of india news

World Cup 2019

Trending Topics

LATEST VIDEOS

More from TOI

Navbharat Times

Featured Today in Travel

Quick Links

Rajasthan election 2019Andhra Lok Sabha electionGujarat Election 2019Karnataka Election 2019MP Lok Sabha electionMaharashtra election 2019West Bengal Lok SabhaTamil Nadu election 2019UP Election 2019Bihar election 2019UP Election DateAndhra Election DateBihar Election DateAndhra Assembly ElectionLok SabhaMP Election DateMaharashtra Election DateShiv SenaYSRCPTDPWB Election DateJDUCongressBJP newsGujarat Election DateSC ST ActUIDAIIndian ArmyISRO newsSupreme CourtRajasthan Election DateTelangana Election DateTamilrockers 2018Uttarakhand newsSikkim newsOrrisa newsKarnataka Election DateNagaland newsSatta KingManipur newsMeghalaya news

Get the app