THE nine-year-old gasps twice before she speaks, haltingly, in English, “I… I am Rakhi. I am studying in Class 4.” For those tense seconds, Rakhi stands stiff, staring at the floor, pinching the seams of her coffee brown uniform kurta.

The mountain of a task done, she tosses back her hair, breaks into a high-wattage smile and sticks out her hand: “How are you? How was your day?” But her teacher Kamlesh Mittal isn’t letting her off soon. “Here, do some maths,” she says, pushing a long notebook in her direction. “9,999 + 825 + 7,000…,” she says in Hindi. “Dhyan se, seedhi banake (carefully, with the place values right, like a ladder)….”

Mittal, in charge of the primary school in Karimpur in Rajasthan’s Dholpur district, has been a teacher for 31 years. “See how good they are,” she says as Rakhi gets the sum right. “Maths is not a problem for these children. It’s English that they struggle with. And there, we can’t help them much.”

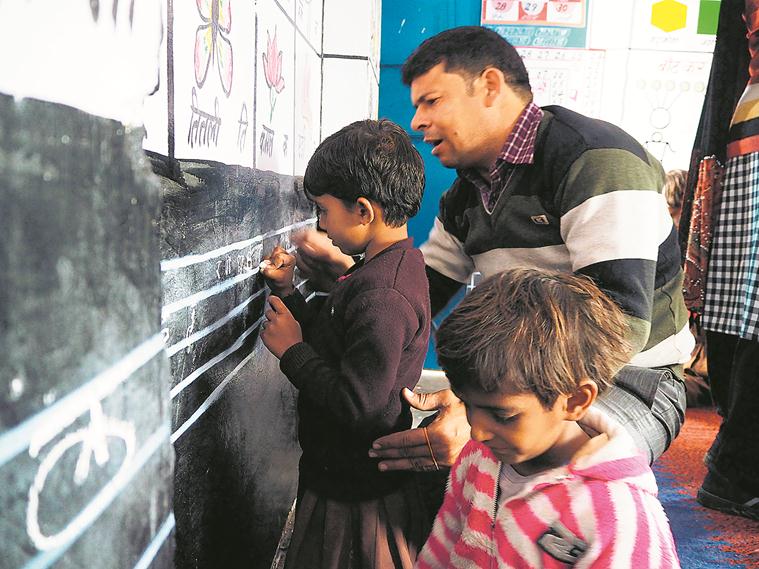

Next, it’s Arman’s turn. He walks up to Mittal’s desk, his brow knit with worry. “Show me how you do this subtraction,” she says, giving him a notebook with two three-digit numbers. As the boy uses his left hand to count, Mittal says, “When Arman got into Class 4, he was terrible at maths. I started by giving him Class 1 maths, sometimes Class 2. Now he comes and asks, ‘Ma’am, what can I solve?’.”

By now, Arman has done the three-digit subtraction and Mittal triumphantly pushes the notebook our way. “See, ek dum theek.” Arman smiles, his brow still knit.

***

Mittal is part of the State Initiative for Quality Education (SIQE), a quiet revolution sweeping through Rajasthan’s government schools, where a focus on improving learning levels has seen an entire department recalibrate its working. From tracking every child’s learning levels to identifying the ones who have fallen behind and teaching them in smaller groups; from teachers making 15-day teaching plans for the class and for individual children; from Activity Based Learning kits to workshops through video conferencing to help teachers make maths and science less dreary, SIQE involves everyone from the local panchayat to the education secretary and all in between — principals, teachers and the students themselves.

The results have been showing. In the last National Achievement Survey (NAS), conducted in 2017, which tests children in Classes 3, 5 and 8 for language, science, mathematics and social studies, Rajasthan scored the highest in Class 8 among all states — language (a state-wide average score of 67%), mathematics (57%), and science (62%). The Sunday Express listed all districts across India according to their NAS Class 8 maths score and of the top 10 districts, six were from Rajasthan, with Nagaur (70.53%), Dholpur (70.11%) and Dausa (68.49%) the Top 3. Besides, in the Performance Grading Index for school education (2017-18) prepared by the Ministry of Human Resource Development and released earlier this year, Rajasthan ranked the highest in ‘learning outcomes and quality’, scoring 168 out of 180 points.

The trigger for much of this churn is classrooms such as Mittal’s.

Behind Mittal’s desk is a pink chart paper with names of all 86 children in the school from Classes 1 to 5. Against each name are two columns — one the child’s class, and the other the “kaksha sthar” or grade level indicating the child’s learning level. Rakhi’s is Class 4, Class 4; Arman’s is Class 4, Class 1.

Of the 69 children from classes 2 to 5 in the school, the learning levels of 54 are not up to grade. Mittal says that when the year began, there were only six children among 18 in Class 5 who were grade appropriate; that number has now gone up to nine.

“By the time they finish Class 5, we have to make sure all these children can do what a Class 5 child should be doing in terms of reading, writing, maths and science. There is a lot of work left,” says Mittal, adding, “But at least now we know what the problem is, which child to focus on.”

In Rajasthan’s government schools, every child in the primary classes has a “portfolio”, usually a paper file which holds his/her worksheets done in class and assessed by the teacher. The file also tracks the child’s progress through three Summative Assessments and internal tests.

Rakhi is Rakhi-I on her yellow portfolio. “That’s because there are two Rakhis in Class 4,” says Mittal, thumbing through Rakhi-I’s worksheets — multiplication sums, an essay on trees, fill in the blanks and a lotus that she has drawn, with the teachers’ comments scrawled along the margins.

The school is by an open sewage pool. “This is not the sight that should be greeting children every morning. Please do something about this,” Mittal tells a group of officials from the Education Department who are on an impromptu visit to the school.

There are other problems too. The school has five classrooms, but only two teachers, so the students from classes 1 to 5 share three classrooms. “We bring small gifts, notebooks, pens, to keep the children motivated. We also get them to do activity-based learning,” she says.

Mittal says she and her husband, who works in the Dholpur collectorate, have sat up several nights to make these props —sthaniya man patti to teach place value; ank seedhi, a game modelled on snakes and ladders; and a way to do addition and subtraction with match sticks. But a favourite with children is gale ka number, for which Mittal has fashioned number tags from old playing cards which children wear around their necks. So for instance, if Rakhi gets the 72 tag, she stays 72 for the entire day and understands the number vis-à-vis other numbers — that 72 is 5 more than Armaan’s 67, 2 more than 70 and so on. “This way, numbers come alive and stay less abstract. It’s good to know that 72 has its uses, that it’s more than just a number that has to be placed in units and tens places,” says Mittal.

Under the SIQE programme, 4,068 schools in Rajasthan — 159 of these in Dholpur — have a designated room for Activity Based Learning (ABL) sessions for the primary grades. The state sanctions Rs 20,000 for these ABL kaksh or rooms — Rs 6,700 for a specially designed ABL kit and Rs 13,300 for the display boards, painting work and desks.

Recognising a “severe learning crisis” in India, the recent draft National Education Policy (NEP) too recommended a similar model of activity-based learning in the primary and pre-primary classes. “Classrooms will allow flexible seating arrangements; learning materials will be safe, stimulating, developmentally appropriate, low cost, and preferably created using environmentally-friendly and locally-sourced materials… (such as) picture cards, puzzles, dominoes, simple musical instruments,” the report said.

The Rajkiya Adarsh Uch Madhyamik Vidyalaya in Vishnoda village, Dholpur, has just completed work on its ABL kaksh. As children sit around in little groups around colourful tables, playing pretend games with fake currency, principal Rajendra Bagela says, “This is how learning should be. We were probably doing it wrong all this while.”

He then joins the children in a song and dance session — about a kagaz ki gudiya (paper doll) without ears, eyes, arms, etc., and how it uses a rabbit’s ears to hear, an owl’s eyes to see and so on.

The Karimpur school doesn’t have an ABL room yet, but Mittal isn’t waiting for one to be sanctioned. “I made these activities myself. I learnt some of this during one of the videoconferencing programmes I attended,” she says.

Across Rajasthan, for two days every two months, teachers assemble in select schools for a live videoconferencing session, during which experts and educationists talk to teachers in far-flung areas about simple activities to make learning fun. These sessions are usually held in model or ‘Adarsh’ schools. There is usually one such school with classes from 1 to 12 in each gram panchayat that acts as a mentor for other schools in the area.

“Each time, over two lakh teachers across 3,000 schools in the state turn up for these videoconferencing sessions,” says Mukesh Garg, Dholpur’s Additional District Programme Coordinator of Samagra Shiksha or SAMSA, an integrated scheme for school education from primary to Class 12.

***

In 2013-14 then chief minister Vasundhara Raje set up the CM’s Advisory Council, with nine sub-groups, including on health, power and education. Led by educationists such as Urvashi Sahni, founder and CEO of the Lucknow-based Study Hall Education Foundation, Gowri Ishwaran, CEO of the Global Education & Leadership Foundation, and Arun Kapur of Delhi’s Vasant Valley School, the education sub-group held a series of deliberations on reforms, with SIQE topping their agenda.

Like several good ideas, this one too would have stayed on paper if not for an army of inspired footsoldiers led by Naresh Pal Gangwar, a 1994-batch IAS officer who came in as Principal Secretary in charge of School Education. Gangwar instantly recognised that the scale was huge and the base dismal — according to the HRD Ministry’s DISE data for 2013-14, Rajasthan had 83,564 government schools with over 64 lakh children and over three lakh teachers, but saw very little by way of learning.

The 2013 Annual Status of Education Survey, conducted by NGO Pratham and released early 2014, showed that only 41.1% of Class 5 government school students nationwide could read a Class 2 textbook and only 20.8% could do division. The figures for Rajasthan were worse — only 35.8% Class 5 students could read a Class 2 textbook and only 15.2% could do division.

Thus began a process of overhaul. To begin with, the complex school organisation system — with multiple buildings and managements for primary, upper primary, and secondary schools — was rationalised. The state carried out one of the biggest school integration exercises, merging more than 17,000 primary and upper primary schools with secondary and higher secondary schools by April 2014, often in the face of resistance by parents, teachers and activists.

The recent Economic Survey too had recommended consolidation or merger of elementary schools to make them viable, given a projected 18.4 per cent decline in the population of children in the 5-14 age group between 2021 and 2041.

There have been more changes in Rajasthan: Adarsh schools were chosen, teachers and principals were given leadership training, 1.25 lakh teachers were recruited and pending promotions cleared. Through all this, a clear line of communication was established — both through the official Shala Darpan, the one-stop portal for everything from student portfolios to teacher vacancies to daily communication, and about 12,000 WhatsApp groups.

“The entire department got synergised. Everybody had a voice and transmission loss was reduced. We got feedback instantly and could start working to rectify or go ahead with what we planned,” says Gangwar, who is now Principal Secretary, Energy.

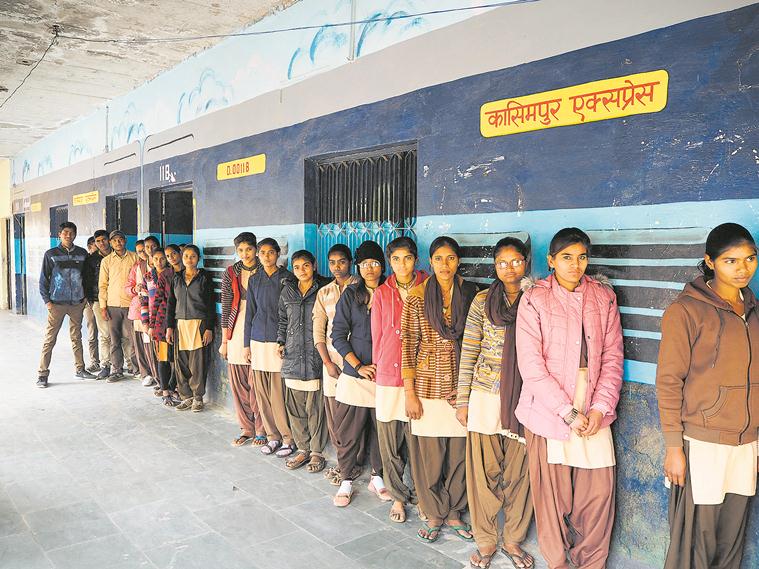

Buildings were spruced and basic facilities such as toilets, drinking water and boundary walls put in place. Many schools got a new look, with a fresh coat of paint and wall paintings. School buildings painted to look like train coaches are currently the most popular design, says Garg, the SAMSA coordinator in Dholpur.

There are, however, challenges. In the absence of adequate funding — the Interim Budget presented in February set aside 16.8% for education — much of this change has depended heavily on individual leaders, especially principals and teachers who have been motivated to, besides contributing money themselves, raise funds from the community through crowdfunding.

Almost every government school in the state has an Akshay Petika, a box where members of the community make donations, anything from as low as Re 1 to a few thousands. The Petika is opened only during meetings of the school management committee, which has parents and community leaders as members. Schools also prominently display a list of ‘Bhamashas’ or members of the village community who have made significant contributions. The money is used to fund anything from sweaters for children to desks and fans in classrooms.

In August 2017, the Department of Education set up Gyan Sankalp, an online portal that encourages individuals, companies and non-profits to adopt a school, make donations or support a project. Since its launch, the government has raised Rs 100.2 crore through the portal.

N K Gupta, State Project Director, SAMSA, admits to other challenges, among them, the quality of teacher training. “Earlier, once teachers got into the system, there was no training of any kind. Now we have six to 10 categories of training. However, we need to improve the quality of training and strengthen DIETs (District Institutes of Education and Training). Many of these DIETS have 50% vacancies,” he says.

Nevertheless, Gupta adds, there’s no going back. “The change that has come in through SIQE is now a regular feature. Governments may come and go but this will continue. We have managed to fill a lot of teacher vacancies, with about 32,000 new teachers since the Congress government took over. Some more are in the pipeline. Once all that is done, there will be less than 5% vacancies,” says Gupta, a 2004-batch IAS officer.

***

Over 500 km from Dholpur, on the state’s eastern fringes, is Nagaur, a district in the catchment area of the Sambhar lake, known more for its salt pans and granite and lignite mines, less for the NAS it topped in 2017.

Nikita Meel knows what it feels to be on top. The daughter of a marble worker in Makarana block of Nagaur, Nikita scored 92.16% in her Class 10, with a perfect A+ in mathematics, earning her a laptop under the Rajasthan government’s Laptop Yojana. “It’s a Lenovo. I left it behind at home. My father uses it, mostly plays games that I taught him. My brother uses it too,” she says.

Under the scheme, the top 6,000 students of the state, besides 100 toppers in each district, get laptops.

Nikita is a student of the Government Surji Devi Kabra Girls Senior Secondary School in Kuchaman block of the district and stays in the government-run Sharade hostel for Classes 9-12. The hostel shares a compound with the Kasturba Gandhi Balika Awasiya Vidyalaya, a residential school for girls from Classes 6 to 8, one of 200-odd such schools in the state for children from SC/ST, backward and minority communities, with 25% seats reserved for EWS.

Nikita’s younger sister studies in the Kasturba school and brother back home in the village.

It’s around 7 pm, dinner time, and the girls are eating soyabean and chapatis, sometimes four to a plate. “We have been together so long, this feels like family,” says Nikita.

A group of girls sit on the steps of the Kasturba building, discussing the plot of Kumkum Bhagya and Kundli Bhagya, two soap operas they watch back to back, from 8 pm to 9 pm. “After dinner, we study for an hour and then come to the TV room. But even if we don’t watch the serials for some days, the story is still the same,” chuckles Priyanka, who is in Class 7 and stays here with her sister.

Priyanka is a member of the school Bal Sansad or Children’s Parliament, a concept introduced by the state government to inculcate a sense of leadership among children. “Mein school ki bhojan mantri hoon aur safai mantri bhi (I am the school’s food and cleanliness minister). I have to make sure children don’t waste food. Also, if they have complaints about the food, I talk to our warden about it. Then there are others — a pradhan mantri, water minister, health minister….”

Warden Sharda Chaudhary, who has been working with the school for 10 years, earning Rs 12,000 a month, says, “This place is like their home. All of them come from extremely deprived families and we do our best to keep them happy. The government sanctions Rs 55 per child, with which we are supposed to provide them milk, toast, breakfast, fruits, tea, lunch and dinner. We end up spending a lot more.”

The following morning, Block Elementary Education Officer Dinesh Singh, who is carrying out an inspection of the MDM (mid-day meal) scheme across the block, makes a stop at the Burdako Ki Dhani Primary School by the main road. He notices two teachers sitting in the verandah outside and asks them, “Why aren’t you in your classes? And why are the children roaming around?”

Bhagwani Mahich, the senior teacher, responds: “Sir, there are only 12 students. Padhane me mazaa tabhi hota hai jab bachche honge (teaching is fun only when there are enough students)….” Singh cuts her short sharply. “If teaching doesn’t interest you, you should find something else to do. There are several people who can take your place,” he says.

As he drives out, Singh says, “See, there are problems. The school has already got a notice for closure. To be fair to the teachers, there are very few homes in this area and they too send children to private schools because the buses come right to their doorsteps. But that’s also why these teachers should work doubly hard — visit homes, show them the portfolios of children so that parents realise how much work goes on in government schools.”

At the Karimpur school in Dholpur, Mittal is playing a game of ank seedhi with the children in one of the rooms. It’s 12.45 pm, minutes left for dispersal. Rakhi’s mother, a cook at the school, turns up at the door and Rakhi asks Mittal if she can leave. As she heads out, she says, “Bade hoke main teacher banungi… aap ki tarah. Achcha, aap teacher nahin hain? Journalist? Phir mein journalist banoongi (I will grow up to be a teacher like you. You are a journalist? I will be a journalist then).”