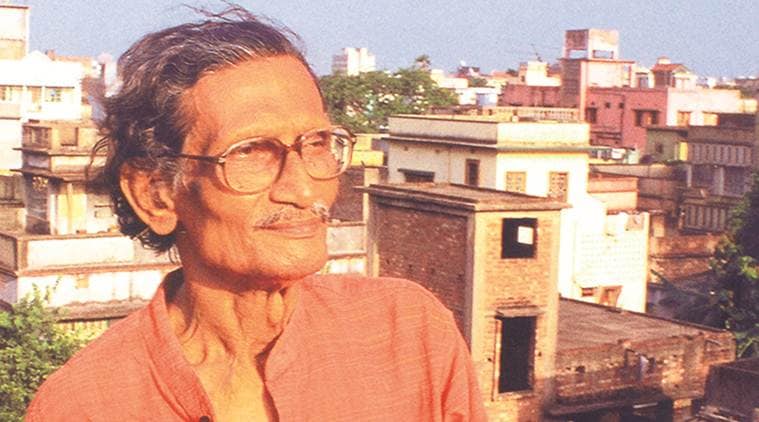

Painted in bold strokes and rich hues, artist Rabin Mondal’s figures often stared at the viewers. They were stark and desolate, reflecting Mondal’s observations of life around him and urging for empathy. He worked towards the endeavour till the very end. On July 2, the Kolkata-based artist breathed his last. He was 90. “His perspective was art that is beautiful is not art. For him, art being a mirror to society was a very important aspect,” says Kishore Singh, Head of Exhibitions and Publications, DAG. The gallery acquired Mondal’s estate over a decade back and organised a retrospective of his work in 2014.

Born in the crowded neighbourhood of Howrah, Mondal was the son of a draughtsman and grew up with meagre finances. Art, for him, was not mere passion but also a means to depict his sentiments and concerns. He first took up drawing and painting at the age of 12, after an injury on his knee confined him to bed for four years, but it was to become a pursuit that he continued for life. Having closely witnessed the horrors of the 1943 Bengal famine and violence and suffering in the years leading to post-Independent India, the human predicament remained his constant subject. “I have always been drawn to the plight of man and his existence for as long as I can remember. Calcutta is the ideal place to observe human life in its many stratums, and I painted humanity as I saw it. The degenerate, dispossessed, debauched, as well as the beautiful — life in its many variations,” stated the artist in the publication Kingdom of Exile: A Rabin Mondal Retrospective.

For Mondal, the journey to becoming an artist was not smooth. Though he joined an art course at Kolkata’s Government School of Art in 1949, he was forced to discontinue due to his family’s limited finances. Working in the family manufacturing unit, he completed a commerce course at Vidyasagar College. In 1955, he was employed by the Indian Railways, and soon joined evening classes at the Indian Art School in Calcutta. Even though his first solo in 1962 at the Academy of Fine Arts in Calcutta was well-received and he exhibited across India with fellow members of the Calcutta Painters Group, established in 1964, he continued his full-time job because there was no market for art . “He was extremely simple. There was no artistic ego or pride that he made such powerful work,” says artist Manu Parekh, who first met him when he was in Kolkata in the ’60s. He adds, “He was not interested in the market at all.”

A member of the Communist Party for a brief period, for Mondal, art was also a means of protest. Primitivist and expressionist, his works often depicted political apathy. One of his most recognised series featured the “king” and “queen” as traumatised figures who were ironically called kings and queens. Exhibited at the Shanghai Biennale in 2016, talking about the series from the ’70s, Singh says, “He looked at people in the position of power and recognised how they made themselves vulnerable — that is the quintessence of the ‘King’ series. The way he was able to craft the fact that power, which for many people is an end in itself, is actually something that unhinges people, takes them away from reality.”

It was perhaps Mondal himself who best described his art, when in Kingdom of Exile: A Rabin Mondal Retrospective, he stated, “I have faced strife and turmoil. I have known great pain. If you are fortunate, you experience seasons of light and darkness — for me, however, it has largely been darkness and more darkness. Light was for others to claim, I just looked on.”