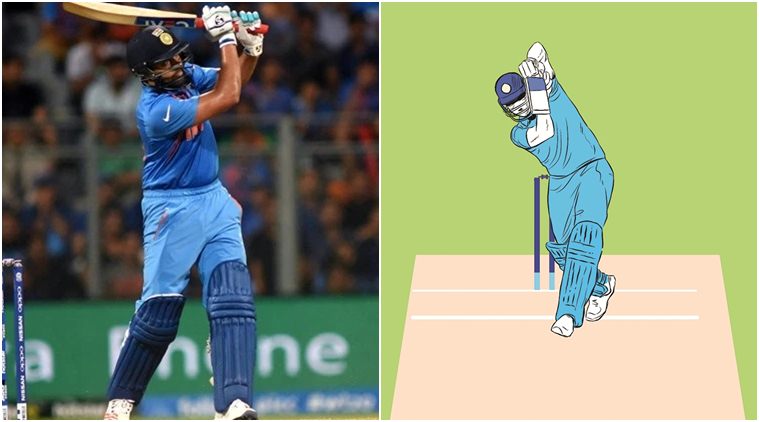

It’s the strangest thing to say about an opening batsman with a quiver full of gorgeous shots but Rohit Sharma has the most beautiful lofted-straight drive in the world. That shot is usually the preserve of big hitters who come down the order. Size up and swing. Your garden-variety hitter would ping long-on, some like Darren Bravo would unfurl lofted hits over mid-off, but no one does it as straight and pretty as Sharma.

The shot of the match came in the 23rd over. Mustafizur Rehman sent it down with the best of intent. Even holding it back a bit. It squirted off a length and moved towards its undeserved fate. Sharma was waiting. He always is.

READ | Hardik Pandya’s crucial strikes derail Bangladesh chase, India in semifinals

Especially, the Sharma of the last couple of years. The knees bend a touch, but apart from that, not much moves. Then seldom has a batsman uncoiled with such grace: the way the bat moves up and down, the way the hands glide, and the ball soared up and over even as Sharma held his pose.

The way his hands moved through the shot and ended up in the frozen pose was as if he picked his little daughter and threw her up in the air as dads do. Gentle, graceful, delightful.

Now, a bit about that waiting in the crease. More often than not, like with his pull shots, he gives the impression that he was actually waiting for the ball, ready with his shot (most of the sixes he hits against the seamers). It’s an illusion, of course, created by the stillness and the balance at the crease. As if he had been expecting the ball to be where he wanted it to be. Usually, it’s a short ball. Usually, it’s that pull.

But at times, his responses to length deliveries, like it did against Mustafizur, gives that illusion.

READ | Rohit Sharma becomes leading run scorer of World Cup 2019

Sometimes contrasting with another batsman helps in making the point better. And so, lets take KL Rahul. Not an entirely unfair comparison as he is an eminently watchable batsman, but the point here is about the balance at the crease while waiting. Rahul plays from the crease while Sharma makes precise movements but at the crease, while waiting, just as the ball is about to be released, Rahul makes some unnecessary little movements that upset his balance.

Why does he do it then? Perhaps, because it’s almost unnatural and extremely difficult to stay still. Picture this: a fast bowler steaming in and you are waiting. The crowd screaming, adrenalin pumping in you, and despite you telling yourself to stay calm, it isn’t easy to be so.

Martin Crowe would say how he would keep muttering, ‘watch the ball, watch the ball’ as the bowler runs in. To kill other thoughts that are flooding in – self-doubts or an aggressive intent, or a pre-determined thought.

READ | ’24 carat Bumrah’ drowns Tigers at Edgbaston

A batsman wants to have a blank mind. But it isn’t easy. They aren’t Maharishis or meditative monks out there. How can you be relaxed? At least look relaxed? Sharma does it.

Watch him next time as the bowler is running in. Thud, thud thud – and he is still. Sometimes, as the bowler gets close to the umpire, Sharma might flex his knees, like a golfer. That’s about it. Occasionally, his hands jar – scratch that, wrong adjective for him, sort of rock the baby, his bat. That’s it, really. Then whoosh comes down the bat, meets the ball.

And that’s why the bowlers most successful are the ones who upset that balance. Make him move at the crease.

Not the short-ball tripe that Pakistan served first game and also Bangladesh. He will set up a stall and keep slamming out pull shots and lofted hits all day. Usually, it’s the left-arm swing bowler who gets the ball to swing back in that can trouble him.

READ | Rohit Sharma, KL Rahul stitch India’s highest opening partnership at World Cup

Then he has to shed that balance, he opens his stance, is worried whether he is going too much across if he plays it to the onside. For the last few months, he has even that covered – he pats the left-arm curlers to mid-on. No, thank you very much, I am not going to try flicking but it would be interesting to see if India and Australia square off and Mitchell Starc creates that doubt.

Back to that waiting now. What’s the thing you notice the most when Sharma is reeling out the big shots. It’s the absence of something.

The absence of the adrenalin rush you associate with someone who is hitting fast bowlers for sixes over their heads. The modern-day batsmen have honed and practised big hitting so thoroughly that they retain their “shape”. There is nothing visceral about the hitting. You gasp but no sound escapes. For all we know, he could have driven that ball for a single or two.

The way his hands moved would have been almost the same. Sharma doesn’t do cheap thrills.

His is a higher art. And even as it enchants you, it leaves you with bewilderment about modern-day cricket: how they are hitting a lot more than ever, but have somehow extinguished the fire associated with it. Sharma is the best exponent of that art form. Calm, collected, graceful – but something almost unnaturally quiet about his violence.