- 937Shares

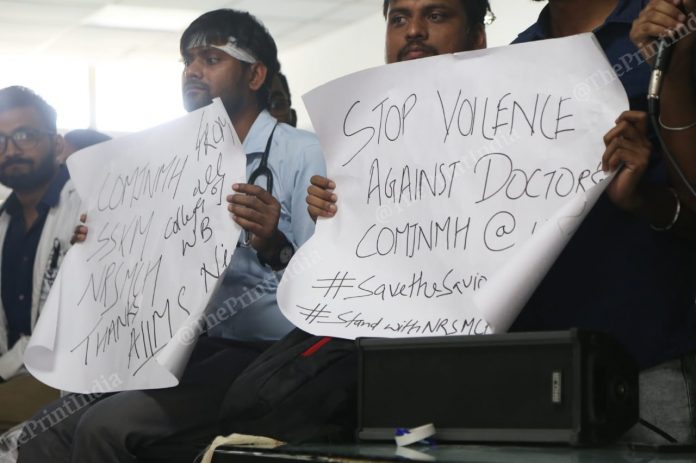

New Delhi: For the last couple of weeks, doctors in India have had the spotlight firmly fixed on them — initially due to the strike sparked by the assault on an intern in a Kolkata hospital and then due to Encephalitis deaths in Bihar and Uttar Pradesh.

But from being understaffed, with India not even meeting the WHO recommended doctor-patient ratio, being underfunded — India is among the countries that spend the least on healthcare — to being overworked, Indian doctors in government hospitals have borne the brunt of a broken system.

On this Doctor’s Day, which honours former West Bengal chief minister Dr Bidhan Chandra Roy, a physician himself, ThePrint looks at what ails the country’s healthcare system.

Just not enough doctors

The Indian healthcare sector is severely understaffed when it comes to doctors. According to data with the National Health Profile report, 2018, each doctor in the country is responsible for nearly 1,453 people against the World Health Organisation recommended ratio of 1 doctor per 1,000 people.

The situation is most acute in Jharkhand where one doctor caters to 8,091 people, followed by Haryana (5,543) and Chhattisgarh (4,616). The situation is no better in the two states that are currently battling the Encephalitis epidemic — in Bihar, one doctor serves 3,240 people while in Uttar Pradesh, a doctor looks after 3,494 of the population.

This has led to a large number of vacancies for doctors across the country. Almost 3,667 sanctioned positions for doctors are lying vacant at various district hospitals, while the figure is worse for sub-divisional hospitals where there are 7,144 vacancies across the country.

The situation is no better in the various other tiers of the national healthcare system. Data in the Rural Health Statistics 2017 show that primary health centres across the country have a shortfall of at least 3,000 doctors, with 1,974 such centres operating without a single doctor. Community health centres in the country have a shortage of at least 5,000 surgeons.

A bleak future

The data also shows that there is little optimism for any improvement in the near future.

According to the Medical Council of India, there are 529 medical colleges in the country, of which 282, or 52 per cent are private institutions. The colleges churn out about 71,000 doctors every year. In contrast, India’s population has been increasing by about 26 million each year.

Moreover, the spread of doctors and medical colleges is not uniform across India. There are states such as Jharkhand, which has three medical colleges, a hangover from the time it was part of Bihar, but has not had a new one since its inception in 2000. In contrast, Gujarat has got 16 new medical colleges in the last decade alone.

Lagging healthcare expenditure

India’s public health expenditure is among the lowest in the world, and the country is in league with nations that spend less than 1.4 per cent of their GDP on health.

According to the National Health Profile, 2018, India at present spends only 1.15 per cent of its GDP on healthcare. This is among the worst even in the neighbourhood — Maldives, Sri Lanka, Bhutan and Thailand spend 9.4 per cent, 1.6 per cent, 2.5 per cent and 2.9 per cent respectively.

The National Health Policy 2017 had set a target of increasing public-health spending to 2.5 per cent of GDP by 2025 but India hasn’t yet met the 2010 target of 2 per cent of GDP.

“The most depressing aspect for the fraternity of doctors in India is the abysmal expenditure of the state on health,” Santanu Sen, president of Indian Medical Association told ThePrint. “This puts extreme pressure on both patients and doctors which culminates on various problems being faced by us such as daily scuffle and violence.”

The lack of spending has led to a huge deficit in infrastructure in the sector.

On a national level, there is a shortfall of 32,900 sub-centres, which are supposed to cater to a population of 5,000 each; 6,430 primary health centres (which caters to 30,000 people) and 2,188 community health centres (addressing health needs of 80,000-120,000 people) in rural areas, as on 31 March 2018.

Also, only 7 per cent of the currently functioning sub-centres, 12 per cent of PHCs and 13 per cent of CHCs are functioning, according to the Indian Public Health Standards (IPHS).

Get the week's top science news with ScientiFix

- 937Shares