Union Budget 2019 Date: On February 28, 2015, at the customary post-Budget press conference, then finance minister Arun Jaitley, who had presented his second Budget, was asked why his Budget lacked even a single big-bang idea. Jaitley was ready for that question. “Many people have told me that you must have a big-bang idea, and I have asked them to suggest one,” he countered. “Give me one big idea that isn’t there.” His questioner was effectively disarmed; no suggestion was offered.

The question over the uninspiring Budget was prompted by the circumstances of that time: it came in the backdrop of a macroeconomic environment that was dramatically on the mend, markedly improved investment sentiment and a sharp turnaround in the global headwinds. So much so that that year’s Economic Survey, the government’s report card tabled in Parliament a day before the Budget, proclaimed that “India has reached a sweet spot — rare in the history of nations — in which it could finally be launched on a double-digit, medium-term growth trajectory”.

Four years down the line, as the newly appointed Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman gears up to present the Union Budget for 2019-20 on July 5, that double-digit growth trajectory is still elusive. While the Budget is expected to outline the economic trajectory for a government that is faced with the onerous task of building on the massive electoral mandate and begin the task of reviving the economy — rekindling growth, arresting flagging consumption and fostering employment opportunities — those watching from the sidelines would be keen to spot that one big idea or policy push. But even before Sitharaman gets up to present her Budget at the appointed hour, an hour before noon, she is headed for the record books — becoming the first full-time woman finance minister (and the second woman ever) to present the Union Budget in Indian Parliament. In 1970-71, then prime minister Indira Gandhi took charge of the finance portfolio after Morarji Desai’s resignation.

A complex balancing act

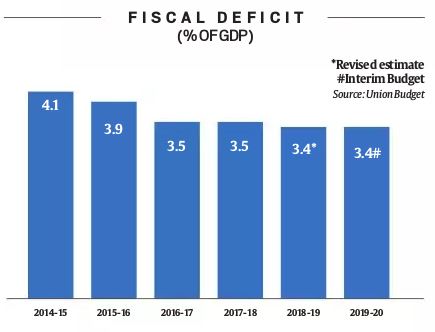

The Budget, though expected to be broadly in line with the interim Budget presented in February by the previous NDA government, will be watched for whether the government opts for fiscal stimulus to spur growth or sticks to fiscal consolidation with an eye on the widening fiscal deficit.

Budgets have moved down in relevance since then, primarily because there is much greater clarity on policy direction and tax trajectory now than a few decades ago, when abrupt changes in licensing rules or tax rates could make or break industries and companies. The Budget format has not changed much either, save for some tinkering with the timing of the presentation and the merger of the railway budget into the main Budget from 2017-18. Despite the progressive loss of relevance, a lingering thread that ties Gandhi’s budget with Sitharaman’s upcoming presentation, through, is the intrigue in the Budget preparation process.

To maintain secrecy, there is a “lock-in” of the officials involved in making of the Budget in the period leading up to its presentation. These officers and staff gain touch with their families only after the presentation of the Budget by the Finance Minister in Parliament. The Budget was earlier printed in Rashtrapati Bhavan, but after an incident in the 1950s, when Budget-related information was leaked by a Rashtrapati Bhavan staffer to some businessmen in Mumbai, the printing of Budget documents was eventually moved to North Block.

Read | Will Budget 2019 bring back inheritance tax? Here’s what the law was like

****

While the Budget is set to be printed in the press at the basement of the Finance Ministry in North Block, the general refrain among officials is that its broad contours are being drawn across the road in South Block. Either way, the biggest significance of the exercise perhaps lies in the signals that the Budget sends out and the broad direction that it charts for the economy. In that sense, there are perhaps four major questions that the upcoming Budget would have to attempt answering:

* Is there a plan to revive growth, especially consumption growth that had been buoyant but is now flagging, alongside other sectors that are visibly struggling — exports, government expenditure and private investment?

* Given that the revenue growth assumptions in the interim Budget presented in February appeared optimistic, due to the slowdown, there is the looming prospect of a downward revision in the revenue expected from taxes in the upcoming Budget. Would this lead to an increase in the targeted fiscal deficit relative to the estimates put out in the interim Budget?

* Will the Budget do anything to sort out the widening mess in the financial sector and where will it find the money to infuse capital into a debt-laden, increasingly stressed sector — the backbone for any resuscitation effort for the broader economy?

* Does the government have the appetite to wade into tougher reform areas that it kept away from in its first stint, including land reforms, labour issues, genuine disinvestment and privatisation etc?

Apart from addressing some of these uncertainties, the Budget could herald a winner in the tug-of-war between those advocating staying the course with fiscal consolidation and those arguing for dithering on the target to enable that there is elbow room to revive the investment cycle by hiking public spending.

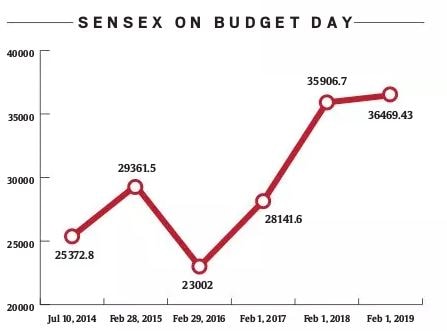

Any deviation from the pre-defined fiscal consolidation glide path could alarm the financial markets and result in a backlash from rating agencies. But given the strained corporate and banking sector books, public spending is necessary to catalyse a rebound in investments. The pro-growth lobby argues that the small fiscal cost would be more than offset by the potential gains from revival of growth. But there’s already a damper. The fiscal deficit for April-May, the first two months of this financial year, has reached Rs 3.66 lakh crore or a whopping 52 per cent of the budgeted target for fiscal deficit for 2019-20, according to official data released on June 28. That seems to suggest that the elbow room is well and truly diminished.

****

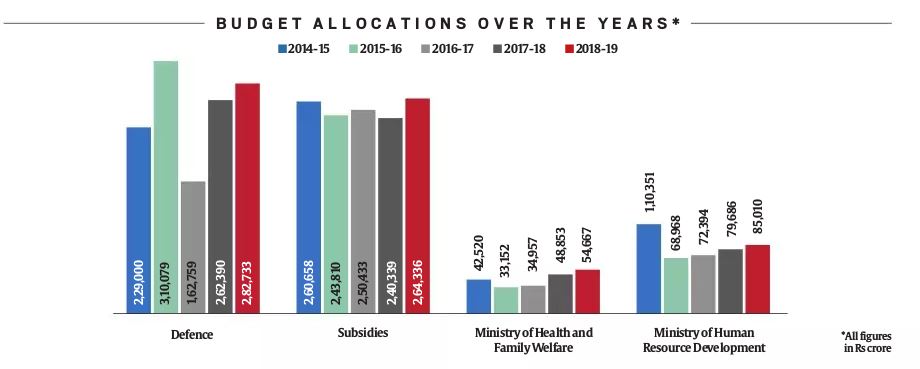

While sticking to fiscal targets has not really been a strong point for the NDA government, each of the six Budgets presented by the Modi government in its last term — though devoid of that one overarching idea — were characterised by a number of piecemeal objectives. This included hikes in income tax exemption limit to Rs 2.5 lakh (Budget 2014-15), a roadmap for cut in corporate tax and the introduction of accidental insurance and pension schemes (Budget 2015-16), Pradhan Mantri Fasal Bima Yojana (Budget 2016-17), electoral bonds (2017-18), and National Health Protection Scheme (2018-19). In its second stint, concerns of the agriculture sector amid a lacklustre monsoon, solutions to tackle unemployment, and a flagship water supply/conservation scheme by the newly formed Ministry of Jal Shakti could be among the priority areas for the government.

Read | A budget wish-list

Budget 2019-20 also comes in the backdrop of looming systemic risks and headwinds, both global and local. While India’s financial system remains stable in the backdrop of improving resilience of the banking sector, the emerging trends in the global economic as well geopolitical environments pose challenges, according to the 19th issue of the Financial Stability Report (FSR) issued by the RBI on June 27. Among the global and domestic macro-financial risks, the report flags significant headwinds faced by global economic activity since the second-half of 2018, culminating in a lower global growth forecast of 3.3 per cent in 2019. Besides, “adverse geopolitical developments and trade tensions are gradually but predictably taking a toll on business and consumer confidence”.

The trade wars playing out across geographies is a broader risk to global growth, which could have a cascading impact on India’s economic growth. India is already drawn into the slugfest and some more changes in the import duty could be anticipated amid the widening trade tussle. India had recently imposed retaliatory tariffs on 28 items following the withdrawal of India’s duty-free benefits under the US select trade programme. Ahead of the G20 meeting, US President Donald Trump termed the action by India as “unacceptable” and called for the withdrawal of the recent increase in tariffs.

The domestic economy has also hit a soft patch recently as private consumption, the key driver of GDP, turned sluggish. This, along with subdued new investment and a widening current account deficit, has exerted pressure on the fiscal front. Reviving private investment demand remains a key challenge going forward while being vigilant about the spillover from global financial markets. The Budget would be perused for policy measures aimed at this objective.

The financial sector, though, is likely to be the biggest bugbear for the new Finance Minister. While credit growth of scheduled commercial banks (SCBs) has picked up, analysts point to the need to further improve the capital adequacy of the SCBs by way of recapitalisation. Money has to be set aside for that, at a time when tax revenues have slowed and new revenue streams are elusive. With the bulk of the legacy non-performing assets (NPAs) already recognised in the banking books and the NPA cycle having seemingly turned around, recent developments in the non-banking financial companies or NBFC sector do not inspire confidence. A cascading impact of the widening NBFC crisis is a big worry, given that these shadow banks have largely fuelled growth outside of the metros so far.

A keenly watched element would be if the Budget factors in a one-time transfer from the RBI for the year. Headed by former RBI governor Bimal Jalan, a panel that is working on recommending an appropriate economic capital framework for the central bank is divided on the issue of transferring past reserves. While most committee members are in favour of reducing RBI’s excess reserves in a phased manner, Finance Secretary Subhash Chandra Garg is learnt to have differed on this view.

Deutsche Bank India said in an internal report to its clients earlier this month that the Centre may have windfall gains this fiscal in the form of higher central bank dividend at Rs 1 lakh crore. “There is a possibility that the authorities will likely use the

Rs 1 trillion one-off transfers from RBI to fund social welfare programmes and boost the expenditure side of the budget,” the Bank said in its note.

****

Analysts do not see any radical alterations in this Budget. According to Aditi Nayar, Principal Economist of credit rating agency ICRA, “With few expenditure allocations expected to be altered from the interim Budget estimates, the upcoming Budget is unlikely to reveal revised priorities of the new government. The long-term path for fiscal consolidation will become clear after the recommendations of the FFC (Fifteenth Finance Commission) become available. Moreover, the magnitude of central transfers to states, particularly through tax devolution, would also become clear after the FFC report, which would significantly impact the government’s fiscal balances in the future.”

A nudge would be also required for sectors that have been displaying symptoms of slackening demand and structural constraints. Two sectors, which played a pivotal role in the UPA growth years and that are now struggling — telecommunications and aviation — are crying for attention. The Telecom Ministry has started work on a revival package for BSNL and MTNL, while the state-owned carrier, Air India, may again go through the disinvestment route after a failed attempt last May.

Some of the changes that India, as well as other emerging market economies, have progressively incorporated in the broader Budget-making process, have been received well internationally, including quantitative output and outcome performance indicators established for each ministry’s spending plan.

“While many emerging market governments present their Budgets on a programme basis, since 2010, a number have implemented reforms designed to link these allocations to performance. Both China and India have established quantitative output and outcome performance indicators for each of their line ministries’ expenditure programmes. From 2014, annual reporting on the achievements and efficiency of each government programme will be a requirement in Russia,” the International Monetary Fund has noted in report on budget processes across countries.

By contrast, countries such as the UK have removed centrally imposed and monitored performance targets on line ministries since 2010, which, according to the Fund, could make it difficult to assess the impact of expenditure reductions on public service delivery.

But a number that international observers such as the IMF, global investors and rating agencies would be keenly watching out for is the fiscal deficit estimate. That could be the real test of how well the mandarins in North Block balance the looming financing constraints and the compelling growth imperative. Over to B-day.