Analyses of the factors that contributed to the handsome victory of the BJP in the 2019 elections will continue to compete for attention and popular as well as scholarly acceptance. The political spectrum, however, appears to be hopelessly divided and oblivious to reality. If proponents of Narendra Modi have been reading in the BJP’s electoral success the role of governance, foreign policy, anti-terror aggression and, as a footnote, the many welfare programmes implemented by the Modi government, the anti-BJP forces continue to sulk in the argument that this victory hinged on an almost fraudulent exercise of money power and the consequent use of image projection.

What both sides refuse to publicly acknowledge is the extraordinary coincidence of the demand side of political culture and the supply side of the BJP’s politics almost matching each other neatly — and feeding on each other. The continued dominance of the Modi-led BJP, and the rise of a new majoritarian grammar of politics, needs to be understood in the context of two distinct but not-so-curiously linked characteristics of what I have elsewhere called the “political culture of new India” (essay of the same title in Niraja Gopal Jayal’s edited volume: Re-forming India, Penguin, 2019).

Looking back at the two decades since Congress’s decline began in 1989, one unmistakably comes across the intertwined narratives of victimhood and dominance. Collectively, and also in parts, Indian society has chosen to construct and nurse a sense of victimhood, of having lost the initiative, of being left behind despite the chimera of welfare and equality on the one hand and the lures of the competitive market economy on the other. This sense of victimhood swiftly permeated into the inter-community arena. Obviously, it could easily inflate the pre-existing mega narrative of Hindu victimhood. The other narrative that was shaped almost simultaneously was one seeking self-assertion and dominance. One version of this narrative revolved around the idea of “dreaming”. This involved the grand dream of India becoming a global power but in the arena of intra-societal relations, this resulted in competitive assertion. Shifting away from searching for soft-power assertions, this gave rise to a politics of identity and numeric claims.

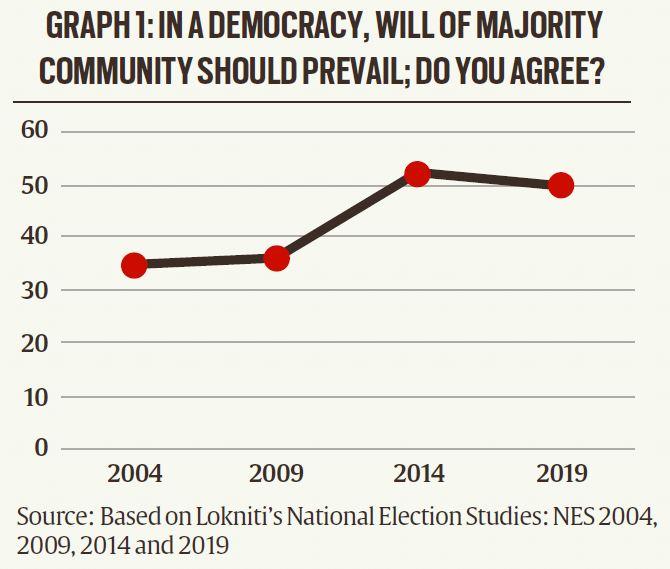

The two narratives suitably gave a fillip to the politics of Hindu assertion and the dream of a Hindu millennium. Through adroit political manoeuvring, the framework of “us and them” got popularised in the backdrop of these narratives. This framework of Hindus as victims, Hindus as majority and Hindus as claimants to Indian nationhood finds resonance with one particular understanding of democracy — the idea that claims made by the majority are a natural corollary of democracy. Over the past decade-and-a-half, this idea of democracy has settled itself quite comfortably in India’s collective imagination of democracy (see Graph 1).

Not surprisingly, the BJP not only contributed to the shaping of this majoritarian sentiment but also articulated it politically. Of course, the moment of the Congress’s decline and the inability of the Mandal constituency to consolidate politically did contribute to the BJP’s success. Even in 2019, its success can be attributed sociologically to the support it received among the OBCs and Adivasis. But over the years, the proportion of majoritarian voters among the BJP’s voters has significantly increased. From under 40 per cent of its voters in 2004 to over 50 per cent of the BJP’s voters in 2019 can be identified as majoritarian. This has happened because the BJP’s political ideology systematically matches the demand side of political culture. The BJP supplies a political platform that gives shape to the sentiments of victimhood while also exacerbating the dreams of dominance as far as the larger construct called the “Hindu society” is concerned. It facilitates the mixing of images as victim (in one’s own land) and owner (of the nation).

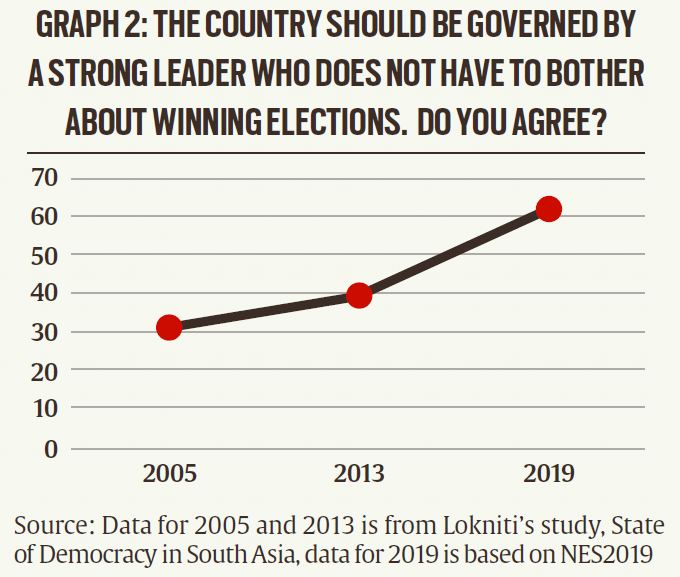

But the narrative of victimhood and dominance also generates yet another political mechanism. Anxieties about both material and cultural universes and the dreams of dominance set off a political expectation of an authoritarian or Bonapartist leadership. During the period when the victim-owner syndrome was taking shape, India’s politics was devoid of any anchor in terms of leadership. In fact, post-1984, the country went on experiencing a leadership crisis. That lacunae along with the collective anxieties must have created a craving for “leadership”. And again, here too, the demand side of political culture found a match in what the BJP supplied since 2014: Modi. In democracies, perhaps more than in non-democracies, there is always an attraction for a “strong leader”. Elections are seen as a fetter in the way of effective stewardship. In India, this sentiment too has been on the rise since 2004-05. From just over 30 per cent, it has reached a somewhat alarming proportion of two in every three by 2019 (see Graph 2).

Interestingly, 40 per cent of the sample in the 2019 study agreed with both propositions — that democracy means an assertion of will of the majority community and that we need a strong leader unencumbered by elections. What complicates matters further is the fact that though the BJP does get larger share among this group, this social section is fairly spread across political parties in terms of its vote preference. This overlap and its cross-party existence suggests that both these emerging political cultural traits are not only interconnected but they also represent a common challenge for conceptualising and practicing democracy. One dimension assumes that community dominance is compatible with democracy if the numbers favour a given community. The other assumes that “popularity” of the leader is the sole source of authority, making democracy and popularity coterminous.

Thus, the two traits comprising the political culture of contemporary India not only help us partially unravel the secret of the BJP’s second victory, they also alert us to the difficult route being taken by India’s democracy — a route where it is not easy to convince many voters that majoritarianism and overdependence on a strong leader are slippery curves in the journey of democracy.

(This article first appeared in the July 26, 2019, print edition under the title Slippery slopes of democracy. The writer is co-director, Lokniti and chief editor, Studies in Indian Politics)