Some second-life packs are already in use here, three housed in a nondescript building from which a rather fine palm tree erupts, several sourced from dead EVs in Madeira. Six batteries have been hooked up so far, their energy potential sufficient to meet the electricity demands of 50 houses for 30 minutes. They could have 10-year second lives, it’s reckoned, although this remains an unknown.

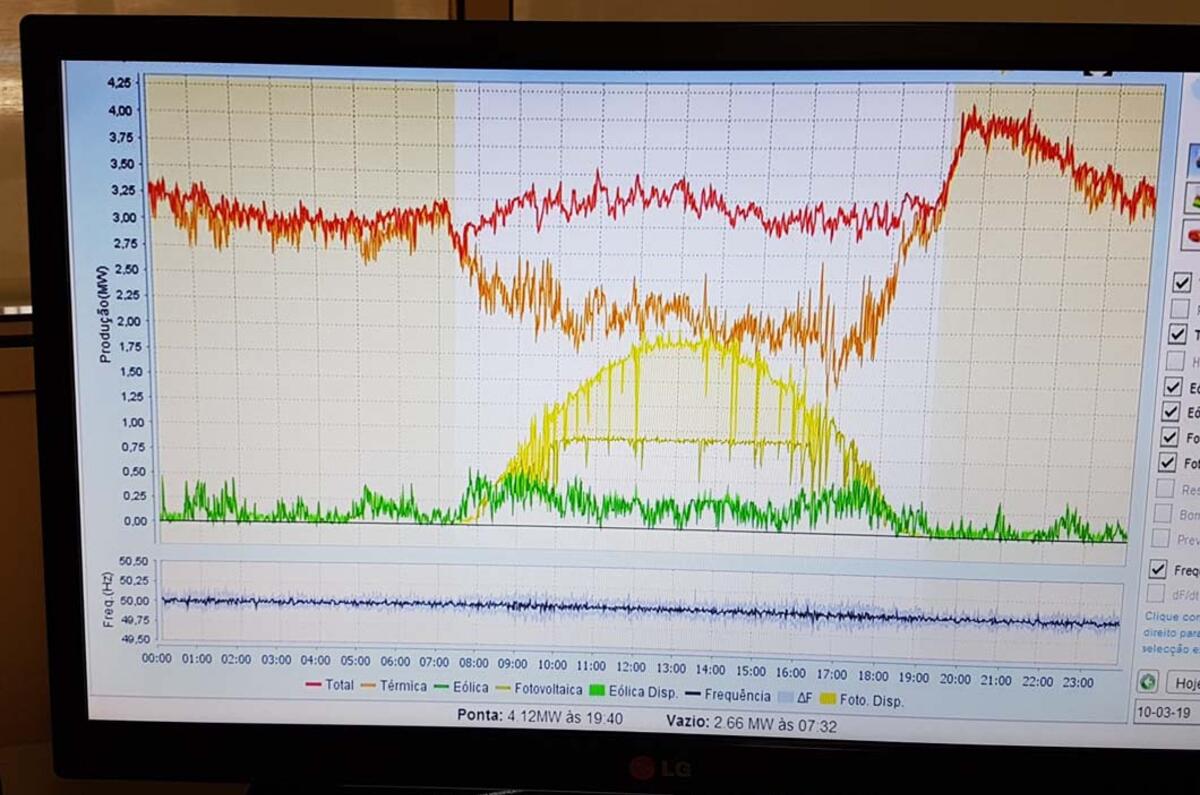

Also unknown is how long it will be before the energy buffering capabilities of EVs are in widespread use. There’s a long, long way to go before we see large-scale, adaptive electricity grids that not only generate power but shuffle it around the battery packs of electric vehicles to overcome the irregular energy generation of renewables. But it clearly makes huge sense to use EV batteries as storage buffers.

From being – literally – a potentially massive drain on national grids, electric vehicles are going to be a vital element in the harnessing of renewables to real-world demand. The Porto Santo project is a tiny step towards this – but, as this so-far-modest fleet of Renaults proves, one with unquestionable benefits.

Growing the vehicle-to-grid network

Part-decarbonising Porto Santo with electric vehicles is one thing, but how will the virtuous circle of EV energy storage get scaled up? Renault is already launching a similar project on Belle-Île-en-Mer in France, with another on Réunion in the Indian Ocean, and has introduced one of the first mainland European vehicle-to-grid schemes, in Utrecht in the Netherlands. Similar localised schemes will appear in France, Germany, Switzerland, Sweden and Denmark too. Why not Britain? “Because there are many energy suppliers,” says Renault’s Eric Feunteun, “so it’s more difficult.”

More obstacles impede these schemes, he adds, one being that not all EVs are bi-directional (including almost all electric Renaults). Another is that there are no specification rules for bi-directional EVs, potentially introducing compatibility issues, while a third is the need to “change customer mindsets”.

But there are incentives, including the fact that it’s possible to make €300 annually from selling your EV’s surplus energy to the grid. That’s fine for owners of EVs with bi-directional capability; those with EVs that can only consume from the grid are nevertheless incentivised (modestly) with €60 annually if they allow their car to stop drawing current during spikes in demand.

Sadly, it’s not practical to retrofit a uni-directional EV with a bi-directional capability, reckons Feunteun. “The labour alone would kill the idea,” he says.

Add your comment