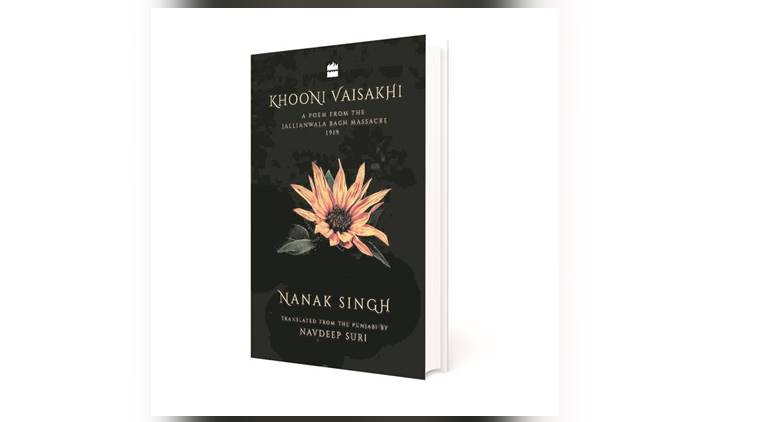

Khooni Vaisakhi: A Poem from the Jallianwala Bagh Massacre, 1919

Nanak Singh (Author), Navdeep Suri (Translator)

Harper Perennial India

144 pages

Rs 399

A dinner-time conversation between Indian diplomat Navdeep Suri and some old friends brought out a level of ignorance about the Jallianwala Bagh massacre. Suri recalls how they mixed up Brigadier General Reginald Dyer (one who ordered the shooting) with Punjab’s Lt Governor Michael O’Dwyer (who ordered the arrest of Satya Pal and Saifuddin Kitchlew).

For Suri, that was a painful moment. After all, his grandfather, Nanak Singh, was at Jallianwala Bagh that fateful afternoon on April 13, 1919, when troops of the British Indian Army, under the command of Reginald Dyer, fired indiscriminately into a crowd of Indians gathered for a peaceful protest to condemn the arrest and deportation of two leaders, Pal and Kitchlew.

And, Singh, a 22-year-old survivor of the massacre, wrote a 900-line poem in May 1920, where he used the poem as a form of protest against the massacre. Published as a pamphlet, it was titled Khooni Vaisakhi. It was promptly banned by the British.

Suri’s father discovered the banned poem after 60 years, since Singh did not talk about the poem during his lifetime, except a passing reference in his autobiography. About a year ago, Suri — currently India’s ambassador to the United Arab Emirates, who has also served as envoy to Egypt and Australia — spoke to his parents, and, the idea to translate this poem into English was born. The result is a masterpiece in translation which remains faithful to the original, not just in content, but rhyme and rhythm.

The poem systematically recounts the entire history of the time: all that took place before that fateful day which led to the order by Dyer to open fire on the public. One of the most powerful lines that depict the incident reads: “Under the tyrant’s orders, they opened fire/ Straight into innocent hearts, my friends./ And fire and fire and fire they did/ Some thousands of bullets were shot, my friends. / Like searing hail they felled our youth/ A tempest not seen before, my friends”.

The translation of the poem is accompanied by a chapter by Suri, who rediscovers his roots — he was born in Amritsar, a stone’s throw away from Jallianwala Bagh, and lived his first eight years there.

In a narrative about his “bauji”, Suri recalls fond memories about Singh, and places the poem in a historical context of 1919. In those 37 pages, Suri carefully describes the time, giving sharp perspective about the massacre and the events leading up to it, and it’s aftermath.

But, the most significant chapter is by BBC journalist Justin Rowlatt, whose great grandfather Sir Sidney Rowlatt, authored the infamous Act that Singh and others were protesting against that day. The Rowlatt Act was dubbed then as “no Dalil, no Vakil, no Appeal.”

In a deeply moving account, Rowlatt, who was BBC’s South Asia correspondent in Delhi between 2015 and 2018, writes about his strong reaction when he went to Jallianwala Bagh. He writes about the sense of conflict in his mind, as he struggled with shame and guilt, due to the acts of his great-grandfather.

The chapter is passionately written and well-argued. Journalist Rowlatt’s courage in accepting what happened was wrong is commendable. “I still am sick to my stomach at the way the British forces behaved in Jallianwala Bagh”, he writes at one place. He also explains how his great-grandfather became a part of this draconian legislation, and refers to some of the previously-unseen private correspondence.

There is also a chapter by professor Harbhajan Singh Bhatia, former dean of languages at Guru Nanak Dev University in Amritsar, where he is effusive in his praise of Singh and his body of work. Singh, who would describe himself as “fourth grade pass or fifth grade fail” learnt to read and write by reading Hindi novelist Munshi Premchand. Bhatia has delved well into the craft of this trailblazing writer, who won the Sahitya Akademi award in 1962 for Ik Myan Do Talwaraan. He wrote an astounding 59 books, which included 38 novels and an assortment of plays, short stories, poems, essays and even a set of translations. His novel Pavitra Paapi (The Watchmaker, translated into English by Suri) was made into a film in 1970, while Chitta Lahu was translated into Russian. His book Adh Khidya Phul (A Life Incomplete) has also been translated by Suri.

Throughout the book, Suri’s tone — in translation of the poem and in his chapter — is one of “lest we forget” about the Jallianwala Bagh massacre.

In a year which has seen many books on the massacre to commemorate its 100th anniversary, what sets this book apart is that it is a contemporaneous account by someone who was actually present there.

The book’s chapters, however, have some typographic errors — the years 2018 and 2015 have been printed, instead of 1918 and 1915. And, in a chapter by Justin Rowlatt, Tushar Gandhi is wrongly identified as Mahatma Gandhi’s grandson — he is actually the great-grandson.

At 127-pages, however, this book is an essential quick-read for those who want to dive into Singh’s powerful poetry and learn about the Rowlatt Act, and, the broader historical context in which the protests and the massacre took place.