Engaged in a game of one-upmanship, botany professor Dr Parimal Tripathi (Dharmendra), the protagonist of Hrishikesh Mukherjee’s Chupke Chupke (1975), turns up at the Mumbai home of his brother-in-law Raghav Sharma (Om Prakash) as a driver from Allahabad. His qualifications include not only good driving but also mastery over chaste Hindi and Urdu.

The reason for this practical joke is to prove to his wife Sulekha (Sharmila Tagore), who hero-worships Raghav, that the brother-in-law is not as sharp as she imagines him to be. Parimal, however, has misgivings about the practical joke; in a call to Sulekha’s brother Haripad Chaturvedi (David), he says: “The only thing I feel bad about is making fun of a language that too my mother tongue.” Haripad replies: “A language is always so great that one can’t really make fun of it. You are making fun of a person.”

The futility of the desire to speak in the pure form of a language — be in Hindi or Urdu — is revealed in an early scene of Chupke Chupke, where Parimal, now playing the driver Pyaremohan, pushes the envelope a bit too far:

Learning and using a language accurately is an unexceptional ambition. But the desire to determine the purity of a language, or to favour one of over another, or even to make one learn it against one’s wish can disintegrate into an ill-fated project, as the recent history of the subcontinent has displayed time and again.

Language is, of course, a deeply emotional issue. Earlier this month, a government-appointed committee on the National Education Policy, headed by former Indian Space Research Organisation chief K Kasturirangan, dropped a clause from the draft of the policy that recommended mandatory Hindi teaching in all schools, after intense protests especially in Tamil Nadu and other non-Hindi speaking states.

The Hindi-Urdu controversy, which began in 1867 when some prominent Hindus of Banaras (Varanasi) demanded that the Nagri script be incorporated for official use rather than the Persian script, pushed forward the Two-Nation Theory leading to the cartographic cosmetic surgery of 1947 and the creation of India and Pakistan.

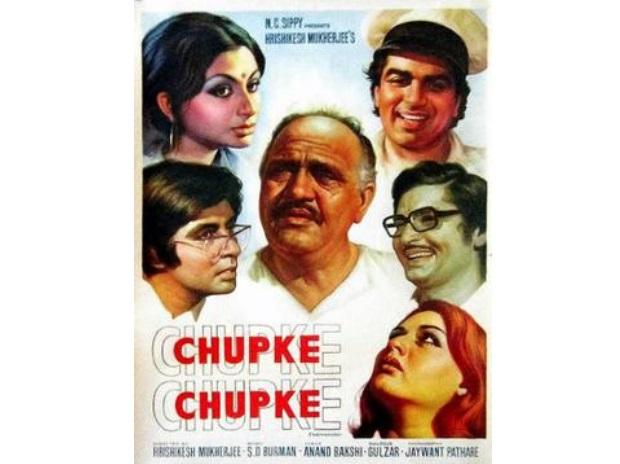

Hrishikesh Mukherjee’s Chupke Chupke

In turn, the alleged imposition of Urdu on Bengali-speaking Muslim in erstwhile East Pakistan led to the Bhasha Andolon in 1952 — and the eventual independence movement in Bangladesh. And in a somewhat strange twist, the fear of imposition of Bengali on Nepalese-speaking people in north Bengal, especially Darjeeling, has been the cause of tension in West Bengal even recently.

Chupke Chupke was, in fact, adapted from the 1971 Bengali caper, Chhadmabeshi, which similarly ridicules one man’s obsession with pure Bengali. In the following scene, he interviews a prospective driver, testing him not on his skills in driving but on his ability to spell difficult Bengali words and English grammar:

In the right hands, language is also a weapon. Shakespeare manipulated language in many ways to expresses distinction — for instance, in plays such as Julius Caesar and A Midsummer Night’s Dream, upper-class characters routinely speak in verse and working-class people in prose. Satyajit Ray uses a similar technique in Hirak Rajar Deshe (1980), where almost all characters speak in a somewhat childish rhyme, while the voice of reason, the schoolteacher Udayan speaks prose.

Hrishikesh Mukherjee also uses language to comment on class in Chupke Chupke. One of the reasons why Raghav wants his driver to speak pure Hindi is so that his daughter’s language does not get corrupted by the Mumbai patois.

The speaker of this much-reviled tongue in the film is the other driver in Raghav’s household, James (Keshto Mukherjee). James is possibly Goanese and Catholic, conforming to the stereotype of bad language, simpleton and drunkard. However, Hrishikesh Mukherjee complicates matters by making him an aspiring Urdu poet. What he tries to write in his drunken stupor might be doggerel, but he knows enough Urdu to recognise a Ghalib couplet when it is quoted to him.

This talent is, of course, hidden from his employer Raghav, who can only treat him with contempt for his inability to speak better Hindi. Naturally, in the comic world of Hrishikesh Mukherjee, the agent of Raghav’s re-education must also be a driver, albeit in disguise.

The suggestion seems to be that learning one language to perfection need not necessarily be a sign of refinement — or, in fact, of anything at all, since, both language and culture are always enriched by corruption. Lovers of purity — linguistic or otherwise — might find Chupke Chupke an illustrative experience; if not, it is anyway funny as hell.