After former Chief Economic Adviser Arvind Subramanian, writing in The Indian Express, kick-started a debate with his new research that India’s GDP growth rates were overestimated, the government said GDP estimates are based on “accepted procedures, methodologies and available data and objectively measure the contribution of various sectors in the economy”.

The methodology of compilation of macro aggregates has been discussed in detail by a committee comprising experts from academia, National Statistical Commission, Indian Statistical Institute (ISI), Reserve Bank of India (RBI), Ministries of Finance, Corporate Affairs, Agriculture, NITI Aayog and selected State Government, the Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation (MoSPI) said in a statement. “.decisions taken are unanimous and collective after taking into consideration the data availability and methodological aspects before recommending the most appropriate approach,” it said.

Subramanian, in a recent research paper published at Harvard University that formed the basis of his piece in The Indian Express Tuesday, concluded that the country’s growth has been overestimated by around 2.5 percentage points between 2011-12 and 2016-17. While official estimates pegged average annual growth at around 7 per cent during this period, actual GDP growth is likely to have been lower, at around 4.5 per cent, he said.

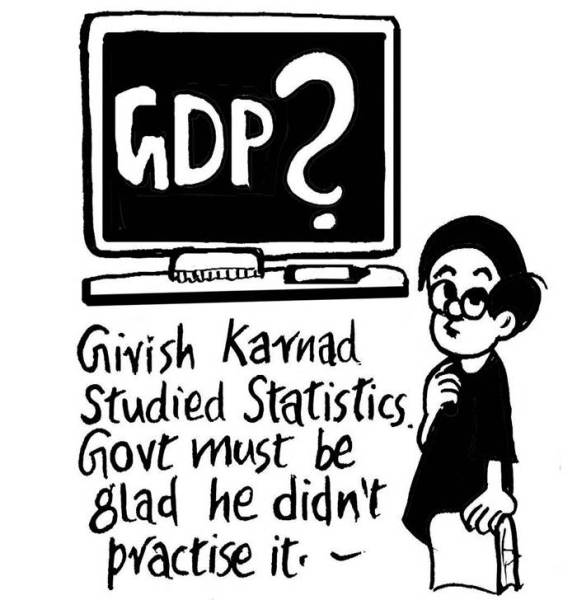

While some economists and statisticians supported Subramanian’s view and the call for an independent panel to examine the GDP estimates, some disagreed stating he didn’t take into account the value indices to measure growth.

P C Mohanan, former acting Chairman of the National Statistical Commission and R Nagaraj, a professor at Indira Gandhi Institute of Development Research, pointed to dissonance in data and called for an expert panel to review the entire GDP revision process.

Pronab Sen, Country Director for the India Programme of the International Growth Centre and former Chief Statistician of India said:

“Before the switch to 2011-12 methodology (from 2004-05), volume indices were being used for estimating growth and volume indices do not capture productivity and value addition. So, a 7 per cent growth could be because of 4.5 per cent volume growth and the rest 2.5 per cent because of productivity. That does not make it overestimation. In fact, if this theory holds true, then we were possibly underestimating growth before 2011-12 as we were using volume-based indicators.”

Mohanan echoed the need for a review. “Ever since the new GDP series was released, experts have been pointing out some dissonance in data with some indicators. While the broad methodology is available, the detailed data are not in public domain. This makes it difficult to comment on the numbers generated by CSO. A thorough review by an expert panel should be constituted to clear the doubts and answer the questions,” he said.

The MoSPI statement said the base year of the GDP Series was revised from 2004-05 to 2011-12 (released on January 30, 2015) after adaptation of the sources and methods in line with the System of National Accounts 2008 evolved in the UN.

According to MoSPI, Subramanian’s research is primarily based on an analysis of indicators, like electricity consumption, two-wheeler sales, commercial vehicle sales etc using an econometric model and associated assumptions. The estimation of GDP in any economy is a complex exercise where several measures and metrics are evolved to better measure the performance of the economy, it said, adding that “with any base revision, as new and more regular data sources become available, it is important to note that a comparison of the old and new series are not amenable to simplistic macro-econometric modelling”.

When asked if the possible overestimation could have affected policy decisions, as has been claimed by Subramanian, Sen said: “Policy has to be contingent upon what are the drivers of growth, especially good growth. If we look at the argument in this manner, then the whole macro narrative changes, especially if we see the link between growth and employment. Because when growth is due to rise in productivity, employment is not going to increase. The way you interpret the macroeconomic picture, that makes the difference.”

Nagaraj of IGIDR said that he has been saying since 2015 that the GDP growth rate seems overestimated though he did not have a precise number for it. The credibility of the revised GDP series is surely dented, and it has affected policymaking, as well as corporate decision making. “I understand many financial firms, especially global firms have stopped using Indian GDP, instead, they depend on the industry and sectoral data. I am told many of them also use the World Bank’s night light data to understand growth in economic activity,” Nagaraj said.

He said the only solution is to undertake a statistical audit of the GDP revision process and set up an independent commission of global experts to thoroughly review all aspects of India’s national accounts.