- 136Shares

In the 2019 elections, 715 out of the more than 8,500 candidates in the fray were women, and 78 made it into the new Lok Sabha. This will increase the share of women in the Lok Sabha from about 12 per cent to about 14 per cent. In most parts of the world, it is women from dominant social groups who are most likely to make it into politics, but not in India.

Over the past 30 years, more women have been fielded from and won SC/ST-reserved seats than general-category seats. This means that much of the increase in women’s representation in Indian politics is happening at the cost of SC/ST men rather than general-category men.

Women from marginalised groups

A common concern in discussions about increasing the presence of both women and minorities in elected politics worldwide is that it is difficult to include women from marginalised groups. Reservations or other quota policies for minorities tend to result in the election of men rather than women, while quotas for women often result in the election of dominant-group women. Women from marginalised communities, who are doubly disadvantaged socially, often end up falling between the cracks of the institutional efforts to make political institutions more diverse.

This is not a concern, however, in India’s local-level politics like panchayat and municipal elections since there are quotas in place not only for women but also for the Scheduled Castes (SCs), Scheduled Tribes (STs) and Other Backward Classes (OBCs). Positions are therefore specifically reserved for women from marginalised communities.

But what happens in elections to the Lok Sabha and the state assemblies?

Here, the historically marginalised SCs and STs have had reserved seats proportional to their share of the population since the first elections were held in 1951, guaranteeing them a political presence. Are women elected in SC/ST-reserved constituencies?

As noticed by Gilles Verniers and Sofia Ammassari of Trivedi Centre of Political Data, in the 2019 general elections, there were more women candidates in ST constituencies – about 13 per cent – than in general-category (8 per cent) and SC-reserved (10 per cent) constituencies. The higher share of ST women candidates was also reflected in the share of winners: 26 per cent of the winners in ST constituencies were women as against 14 per cent in general and SC constituencies.

But the 2019 elections were not unique in bringing more women to power in SC/ST-reserved seats. In fact, in a recent research article, I show that this has been a trend both in Lok Sabha and state assembly elections for the past 30 years.

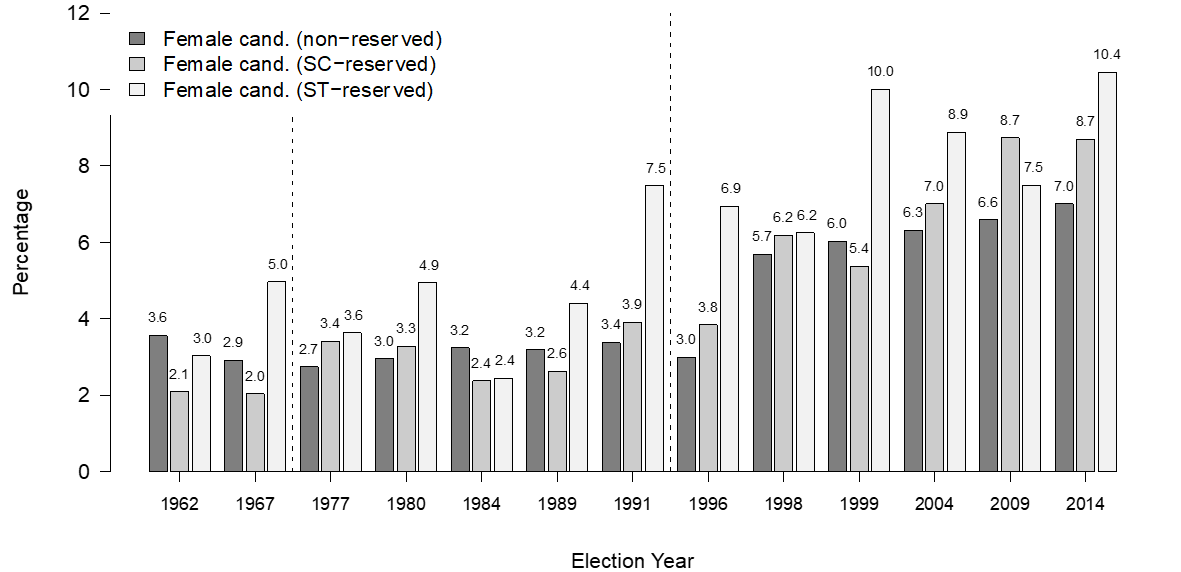

Figure 1: Percentage of female candidates in non-reserved, Scheduled Caste-reserved and Scheduled Tribe-reserved parliamentary constituencies, 1962–2014

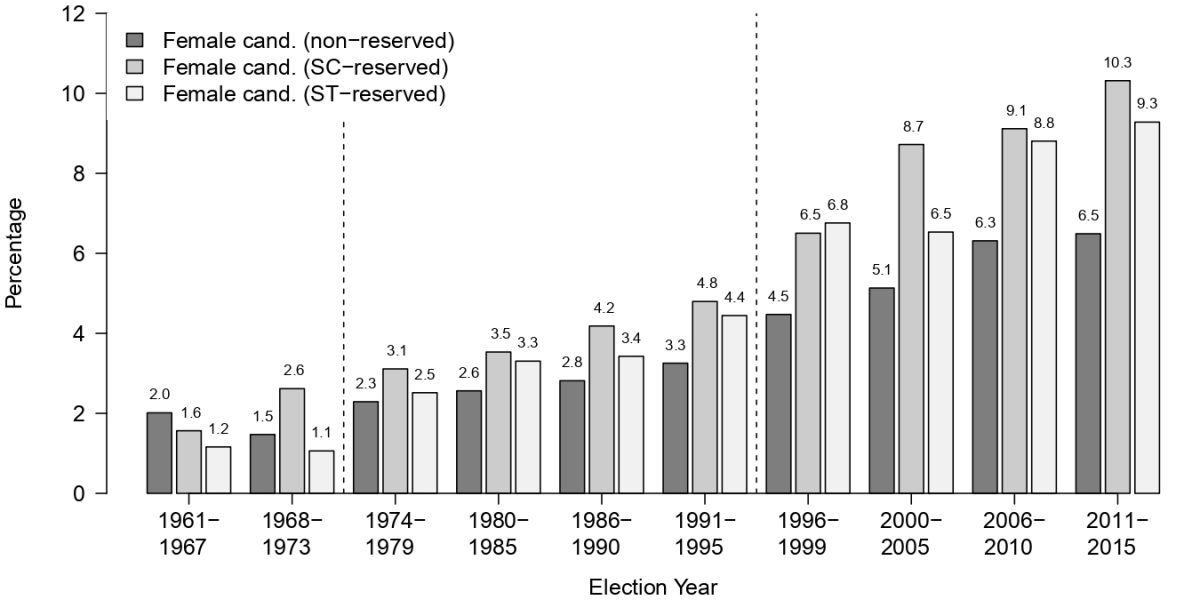

Figure 2: Percentage of female candidates in non-reserved, Scheduled Caste-reserved and Scheduled Tribe-reserved assembly constituencies, 1961–2015

Figures 1 and 2 show the share of female candidates in non-reserved (general) and SC- and ST-reserved constituencies in Lok Sabha elections (1962-2014) and assembly elections (1961-2015). As we can see in Figure 1, until the 1990s, the percentage of women candidates was low across all types of constituencies, although somewhat higher in the ST-reserved constituencies. Since 1991, however, the share of women in reserved constituencies has consistently been somewhat higher.

Looking at data from state assembly elections, as shown in Figure 2, the pattern is even starker: here it seems clear that much of the increase in the nominations of female candidates in recent years has actually taken place in reserved constituencies (with a higher share in SC constituencies than ST and general constituencies).

The difference in nomination patterns is also reflected in the number of women who have won the elections. In the 2014 Lok Sabha elections, 11 per cent of MPs elected in general-category constituencies were women, compared to 14 per cent of MPs from SC-reserved constituencies and 13 per cent from ST-reserved constituencies. In the 2019 elections, this difference is even more pronounced. It is actually the general-category women who have drawn the shortest straw in Indian elections so far.

SC/ST women replace SC/ST men, not general category men

There may be several reasons why SC and ST women have been nominated in somewhat higher numbers than general category women.

A negative interpretation, consistent with literature from other countries, is that as the pressure to bring more women into politics has increased, parties have consciously chosen to replace male SC and ST candidates with women so as to be able to keep as many general-category male candidates as possible.

This may also have happened unintentionally, as SC and ST men tend to have a somewhat weaker position within the party.

A more positive interpretation of SC and ST women being nominated in higher numbers is that the political arena in reserved constituencies is somewhat more open to a more diverse set of candidates per se.

Whatever the reason, it is important to be aware of such patterns, as it is not ideal that women’s entry into politics is happening at the cost of SC/ST men rather than general-category men.

Francesca R. Jensenius is an Associate Professor of Political Science at the University of Oslo. Views are personal.

Get the PrintEssential to make sense of the day's key developments

- 136Shares