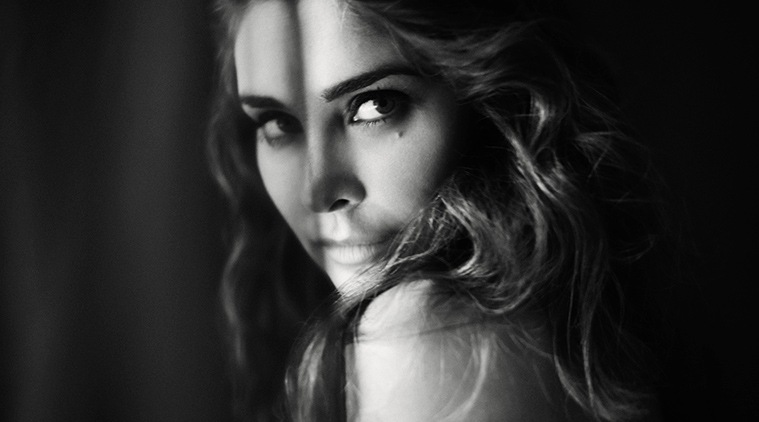

A former supermodel, and a cancer survivor, Lisa Ray became a household name in India, after her appearance as a skilled criminal lawyer in the suspense-thriller Kasoor, opposite Aftab Shivdasani. Over the years, with films like Water, I Can’t Think Straight, and Hollywood/Bollywood, she has proved her mettle as an actor. Despite her accomplishments, Ray chooses to identity herself in her memoir ‘Close to the Bone’ as an outsider.

Growing up in Toronto to a Bengali father and a Polish mother, Ray asserts that she has been a ‘natural outsider’, and perhaps this has helped her to write about her struggles and success with a marked objectivity. In her memoir she highlights her struggle with cancer, but with equal fervour talks about her struggle with eating disorder, of failed relationships and her inability to belong.

Excerpts:

In your memoir Close to the Bone, you treat cancer with marked affection. There is a line, “After years of floating in the wind like a leaf, coming and going, I am ready to feel rooted,” you write after the diagnosis. How did you manage to muster all the courage while going through the process?

What happens when nature makes you challenge all conventional assumptions about life? When your job profile conceals more than it reveals? When you as an introvert and a natural observer spend days in front of a camera? Well, then you become a covert writer; in order to understand, to connect your mind and heart and to transcend yourself. At the same time, you become more intimate with the stories of your heart – hopefully with compassion and often with humour. Writing did not take courage, it has been healing.

You have been refreshingly, and if one might add, brutally honest about your life. Whether it is about sharing your eating disorder or feeling trapped as the diva in Bombay. Such objectivity while writing about oneself is rare. Was it a conscious effort?

Growing up of Bengali-Polish parentage in Toronto in the ’70s, made me a natural outsider.

‘What are you?’ was a constant refrain. ‘Me? I’m different’, I would reply with childish defiance. Though it took me years to understand exactly how my uniqueness was my strength.

But before that, where did that leave me? A mixed blood creature, with the ability to embody multiple worlds and identities and with a puzzling passion for India, the land my father left in his early twenties. Well, apparently, it helped me develop a way to live beyond reason, to constantly question and to seek the pleasure and displacement of living away from where I was born, while also looking for home. Being the observer comes naturally and from there, it’s a short step to candidness and sharing.

The book serves as an excellent commentary on your life, apart from presenting your struggle with cancer. Did the condition, at any point, serve as a trigger for self-introspection?

Yes, but it’s not the only one. My writing perspective today has grown out of an impulse to defend against the world’s growing inability to hide beneath the surface of appearance. Personally, from the vantage point – commonly known as midlife – I can apprehend the harvest of a life of cross-pollination and fluid identity. As someone who has grown through pain and humour, today I see my experiences as an accidental actress and of not belonging as universal and yet useful.

I also write to pay obeisance to the unstoppable force of love which takes many forms: protection, fury, tenderness, boldness and intimacy; each experience inviting deeper knowing of the very human experience of being broken, misunderstood and vulnerable. Ultimate resilience, to me, lies in vulnerability and an ability to open completely to each experience. By going to the borders of yourself, by expanding from there, by failing, by falling, by rising. By unearthing buried instinct. By listening. And laughing.